The Phenuiviruses

In June of 1912, according to the Colonial Report of the East Africa Protectorate, farmers whose sheep grazed the shores of Lake Naivasha in the Rift Valley region of Kenya described a disturbing development: “…The appearance of an obscure disease among young lambs, causing a heavy mortality…”. Many sheep died suddenly, while others suffered spontaneous abortions.

Some 18 years later, on a Merino sheep farm in the same Rift Valley region, 3,500 lambs and 1,200 ewes succumbed to an outbreak of an apparently very similar disease. “Symptoms were very indefinite, and lambs rarely survived 24 hours after they had become visibly ill. Death also followed very promptly the onset of symptoms in ewes,” scientists Robert Daubney and John R. Hudson wrote in a 1931 edition of the Journal of Pathology and Bacteriology. “Some animals were observed to vomit, in some cases there was a thick mucopurulent nasal discharge, and in a small proportion the faeces contained much blood.”

The scientists went on to explain that their laboratory investigations had revealed two further important discoveries: that the disease was one not only of sheep, but also “of cattle and man”; and that it was caused by a viral pathogen. That pathogen—given the name Rift Valley Fever Virus —is now classified as a member of the Phenuivirus family, one of The Viral Most Wanted.

One Big Close-Knit Family?

It’s large, yes—but the Phenuivirus family’s 180 or so members belong to at least 20 separate subgroups and are not all close. Some subgroups, such as the Phleboviruses for example, include several human pathogens like Rift Valley Fever Virus and Dabie Bandavirus that are more closely related to each other than to viruses in the wider family.

Prime Suspects

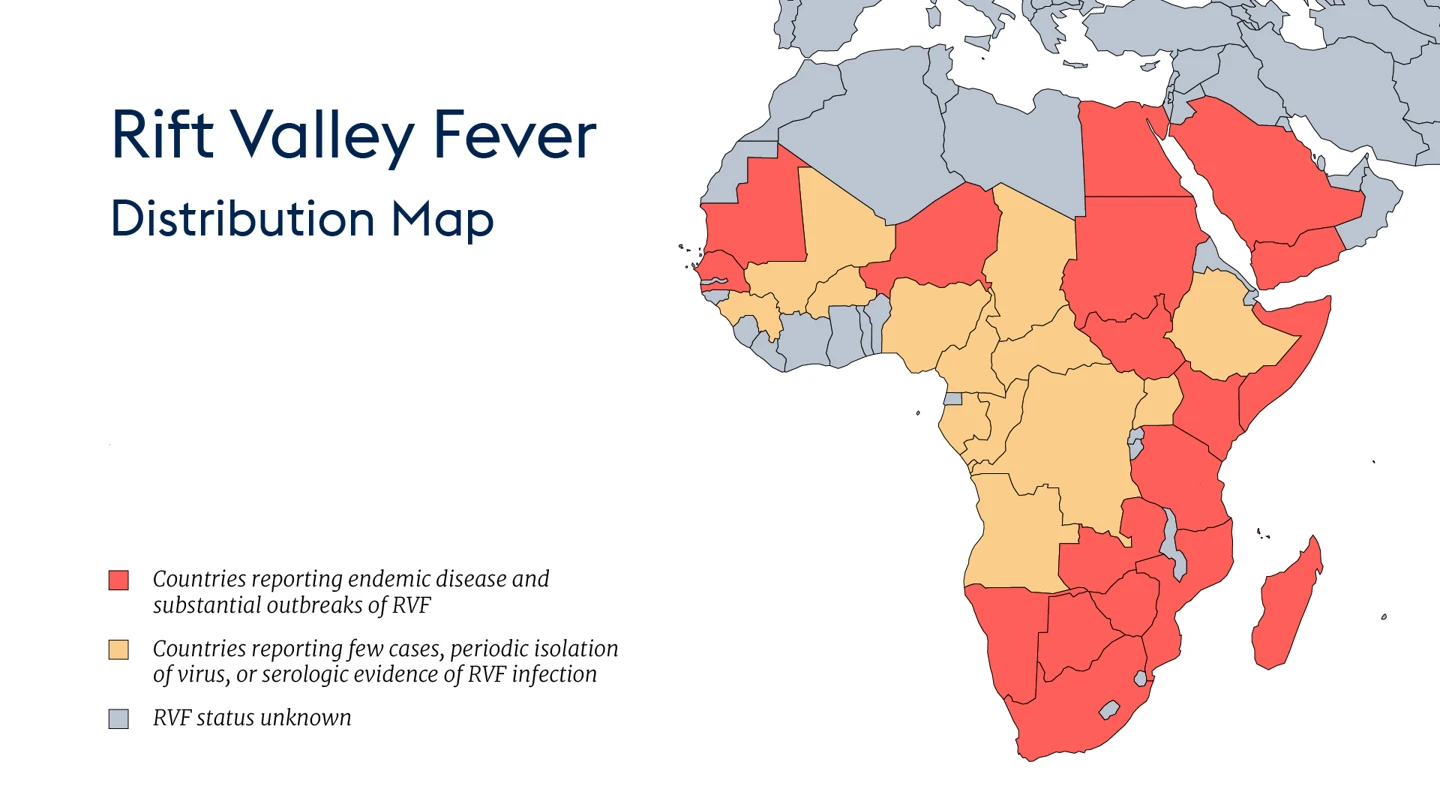

Rift Valley Fever, or RVF, is the most infamous and significant human pathogenic threat in the Phenuivirus Family. While it is mostly a disease of animals—primarily infecting livestock—it can and does also infect people, causing serious disease and dangerous outbreaks.

Dabie Bandavirus—a Phenuivirus that can cause severe fever and a blood condition characterised by a low platelet count known as thrombocytopenia syndrome—is another notable human infection culprit in this family, as is Heartland Virus, which causes similar thrombocytopenia symptoms.

Nicknames and Aliases

The 1931 journal paper that first identified RVF referred to it in its title as “Enzootic Hepatitis or Rift Valley Fever” is also sometimes referred to as Infectious Enzootic Hepatitis of Sheep and Cattle.

Heartland Virus gets its name from the Heartland Regional Medical Center in St. Joseph, Missouri, where it was first identified in 2009.

Dabie Bandavirus is also known as the Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus, or SFTSV. The name Dabie Bandavirus comes from Dabie Mountains area of central China, where the virus was initially discovered.

Distinguishing Features

Phenuivirus virions, or virus particles, are either spherical or pleomorphic—in other words variable in shape. They are relatively small, with diameters ranging from 80 to 160 nanometers. Inside, they contain three segments of single-stranded RNA. Phenuiviruses are typically enveloped viruses, which means they are covered in a cloak or membrane. This viral envelope is covered with glycoprotein spikes, which the viruses use to attach to host cells.

Source: Viral Zone by SwissBioPics

Modus Operandi

Phenuiviruses gain entry to and infect human cells by first binding to specific receptors on the cells’ surfaces. After attaching and being taken in by the host cell, the virus hijacks its machinery to produce new viral proteins and RNA to form new viral particles. These then go on to infect further cells, replicate and spread.

Accomplices

Rift Valley Fever Virus does not necessarily need accomplices to help it spread disease and death, but it uses them nonetheless. Mosquitoes—particularly Aedes and Culex mosquitoes—are carriers of the disease and can transmit it from infected animals to people through their blood-sucking bites. Blood-feeding or hematophagous flies have also been known to transmit the disease. According to the World Health Organisation, the majority of human Rift Valley Fever infections result from direct contact with the blood or organs of infected animals and to date there has been no known or documented human-to-human transmission.

Dabie Bandavirus and Heartland Virus use ticks as their main accomplices. In the majority of cases of infection in people, they have been transmitted through the bites of infected ticks—in particular Haemaphysalis longicornis or the Asian Long-horned tick, and the Lone Star tick or Amblyomma Americanum. In some cases, however, the viruses can also spread from person to person through direct contact with blood or bodily fluids of someone infected.

Common Victims

The most common victims of Rift Valley Fever are people in sub-Saharan Africa who live or work in close proximity to livestock animals that could be infected. This means farmers, herders, slaughterhouse workers and vets are at highest risk of becoming infected. People in endemic areas who are frequently exposed to mosquitoes, or often bitten by them are also at high risk.

Infamous Outbreaks

Rift Valley Fever

Until the mid-1970s, Rift Valley Fever was thought to be a disease confined to the African continent and one that only really affected animals. Human cases were very rare and usually only caused mild symptoms. But after a season of heavy rain and flooding in South Africa in 1974, a severe outbreak of RVF spread to more than 500,000 animals and into more than 100 people. It was also during this outbreak that the first human RVF deaths were reported, with seven victims unable to fight the viral disease off.

This first known deadly human outbreak in Africa was followed by similarly worrying outbreaks in Egypt in 1977, in Mauritania in 1987. Another epidemic in Kenya and East Africa in 1997–1998 was considered among the most devastating in the region, infecting about 27,500 people and killing more than 400 of them.

By 2000, RVF had spread beyond the African continent for the first time and was detected in Saudi Arabia and Yemen. More than 1,000 people were infected in this RVF outbreak, and at least 123 of them died of the disease.

To date, no human or animal outbreaks of RVF have been recorded in Europe, the Americas, Australia, or New Zealand. But epidemic watchers say environmental change and evolving weather patterns as the planet warms are increasing the risk that RVF-carrying mosquitoes could spread to new countries and regions, bringing the virus with them.

Source: CDC

Dabie Bandavirus

Disease detectives first discovered Dabie Bandavirus, or SFTSV, in 2009 in the Chinese provinces of Hubei and Henan. It went on to cause deadly outbreaks in several more Chinese provinces in 2010 and 2011, and was then reported for the first time in Japan and South Korea in 2013. In 2015, Vietnam and Taiwan also reported Dabie Bandavirus outbreaks in people—evidence of the virus’ steady and menacing spread into new areas of the region.

Heartland Virus

Heartland Virus is very rare and has primarily caused human outbreaks in the midwestern and southern United States since it was first identified in 2009. As of November 2022, disease trackers have recorded 60 cases of Heartland virus infection in people.

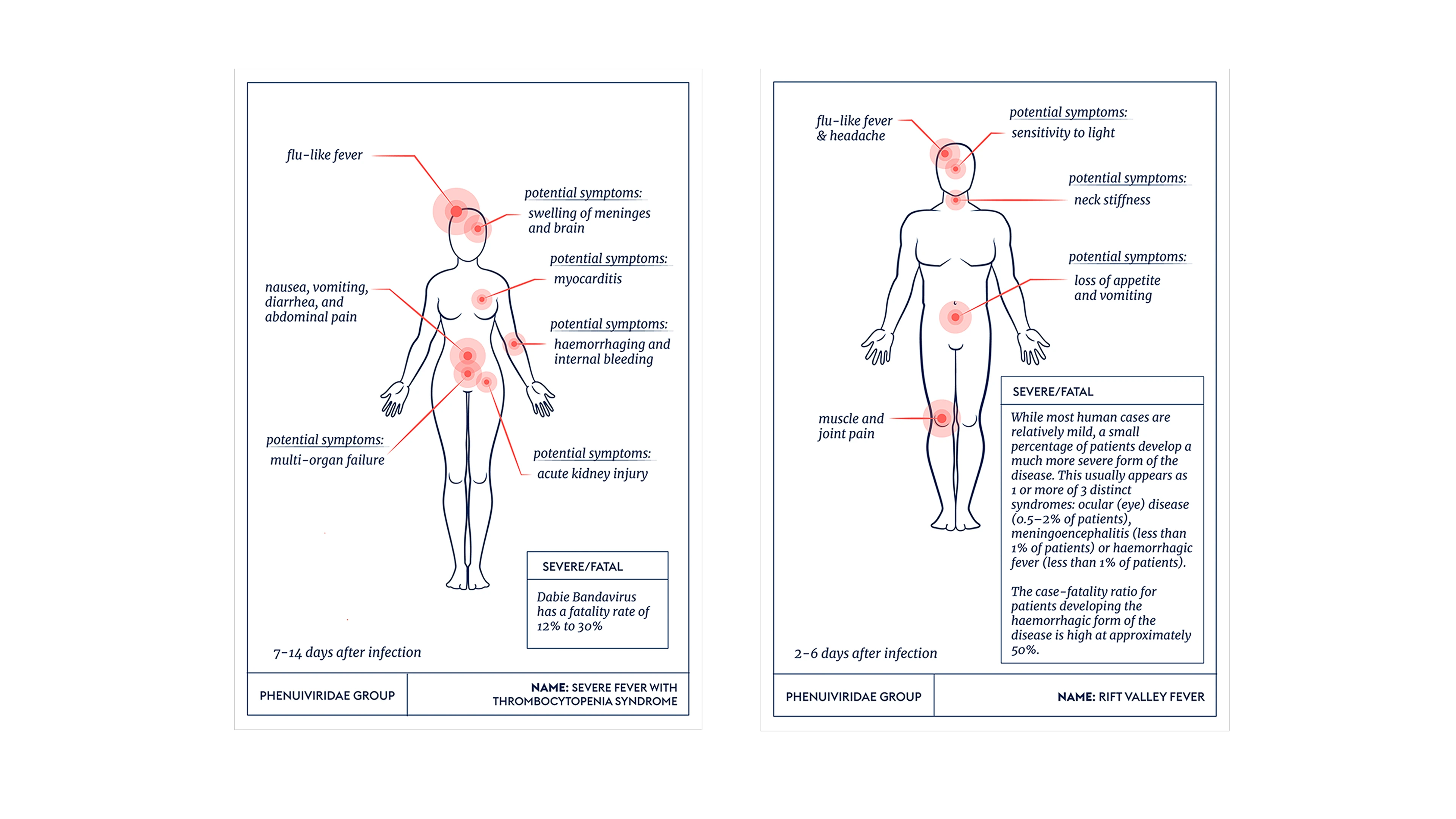

Common Harms

Victims of Dabie Bandavirus can suffer a range of symptoms including high fever, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, internal bleeding, gastrointestinal symptoms, myalgia or muscle pain and swollen lymph nodes. The disease has a fatality rate of up to 30 percent.

Heartland Virus infection in people can induce fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, headache, nausea, diarrhoea, and muscle or joint pain. While the disease is known to have been deadly in some cases, the exact number of human deaths it has caused is not well documented.

Victims of the biggest human killer in the Phenuivirus family—Rift Valley Fever—also suffer a range of symptoms which typically appear between two and six days after they have been exposed to the virus. These include fever, headache, muscle, joint and back pain, and can sometimes progress to problems with the eyes including soreness and blurred vision. The most severe cases suffer internal bleeding (haemorrhage)and encephalitis, or inflammation of the brain, which can lead to seizures, coma and death. The case-fatality rate for people with the haemorrhagic form of the disease is up to 50 percent.

Lines of Enquiry

Because there are as yet no licenced safe and effective human vaccines against members of the Phenuivirus family, scientists around the world are pursuing a number of lines of enquiry into how to protect people from disease outbreaks caused by them.

In particular, given its ever-increasing geographical spread and its heightened threat, Rift Valley fever has become a priority disease for work on the development of human vaccines. CEPI has joined forces with the European Union [Rift Valley Fever | CEPI] on funding initiatives to drive progress on RVF vaccines, including clinical trials of multiple vaccine candidates in East African countries where the disease is endemic.

For Dabie Bandavirus, researchers are also working on innovative ways of defending against the disease, including the development of a vaccine candidate that uses nanoparticles to carry the antigens that contain instructions for fighting off a Dabie Bandavirus attack. In March 2025, CEPI announced a partnership with Nagasaki University in Japan to carry out early research into its 'nanoball' vaccine technology that could protect against the virus.

Editor's note:

The naming and classification of viruses into various families and sub-families is an ever-evolving and sometimes controversial field of science.

As scientific understanding deepens, viruses currently classified as members of one family may be switched or adopted into another family, or be put into a completely new family of their own.

CEPI’s series on The Viral Most Wanted seeks to reflect the most widespread scientific consensus on viral families and their members, and is cross-referenced with the latest reports by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).

Related articles

Related articles

The Arenaviruses

The Arenavirus family includes some of the most lethal haemorrhagic fevers known. All its prime suspects can cause life-threatening disease and death

The Coronaviruses

Seven members of the Coronavirus family are already known to infect people, often with deadly consequences. Disease investigators fear that more new and dangerous Coronaviruses could spill over at any time.

The Filoviruses

“one of the most lethal infections you can think of” - and it's one whose deadly reach is extending ever further

The Flaviviruses

Yellow Fever is now known as one of several deadly viral haemorrhagic fevers currently classified a Flavivirus, one of The Viral Most Wanted.

The Hantaviruses

Some Hantaviruses focus their attacks on blood vessels in the lungs, causing the blood to leak out and ultimately ‘drowning’ their victims.

The Paramyxoviruses

This family contains one of the most contagious human viral diseases, as well as one of the most deadly. Explore The Paramyxoviruses.

The Poxviruses

The viral family of one of the most fearsome contagious diseases in human history

Matonaviruses and Togaviruses

Multiple lines of enquiry against Chikungunya virus and its viral relatives are being pursued by scientists around the world, with the hope for a new protective vaccine coming very soon.

The Nairoviruses

The prime suspect in this family is a deadly virus that causes its human victims to bleed profusely.

The Orthomyxoviruses

These viral culprits have caused the deadliest pandemics in human history

The Retroviruses

The most nefarious Retrovirus—HIV—has infected 85 million and killed 40 million people worldwide.

The Phenuiviruses

The most infamous Phenuivirus, Rift Valley fever, poses a significant threat to people and livestock causing serious disease and dangerous outbreaks.