The Arenaviruses

Dearest Family,

We've had difficult times here. On February 13th, our dear Char Shaw, one of our nurses, went Home to Glory. She had been sick for two weeks with shooting fevers, bad throat and mouth, aching, not responding to antibiotics—a viral infection.

A week before she got sick, a missionary was brought here who died 24 hours later, with the same terminal symptoms that Char developed. At the time of this missionary's death. Char felt that she had gotten contaminated when caring for her.

Yesterday and today, I haven't been feeling well, with a low-grade fever and so I am off duty. Trust this is short-lived. There is no time to be sick. Do pray with us for permanent health.

Lots of love, Lily.

This letter, written from Nigeria in 1969 by an American missionary nurse named Lily Pinneo, tells the story of the emergence of a novel viral haemorrhagic fever in the town of Lassa in northeastern Nigeria, near the border with Cameroon.

The febrile illness, which soon inherited the name of the town and became known as Lassa Fever, was later found to be caused by a virus related to another called Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis virus, or LCMV. Both these viruses are spread by rodents such as rats, mice and voles, and can cause severe disease in people. Both are also members of the Arenavirus family—one of The Viral Most Wanted.

One Big Close-Knit Family?

Pretty much so, yes. The Arenavirus family has scores of viruses in it, several of which are known to infect and cause disease in people as well as animals.

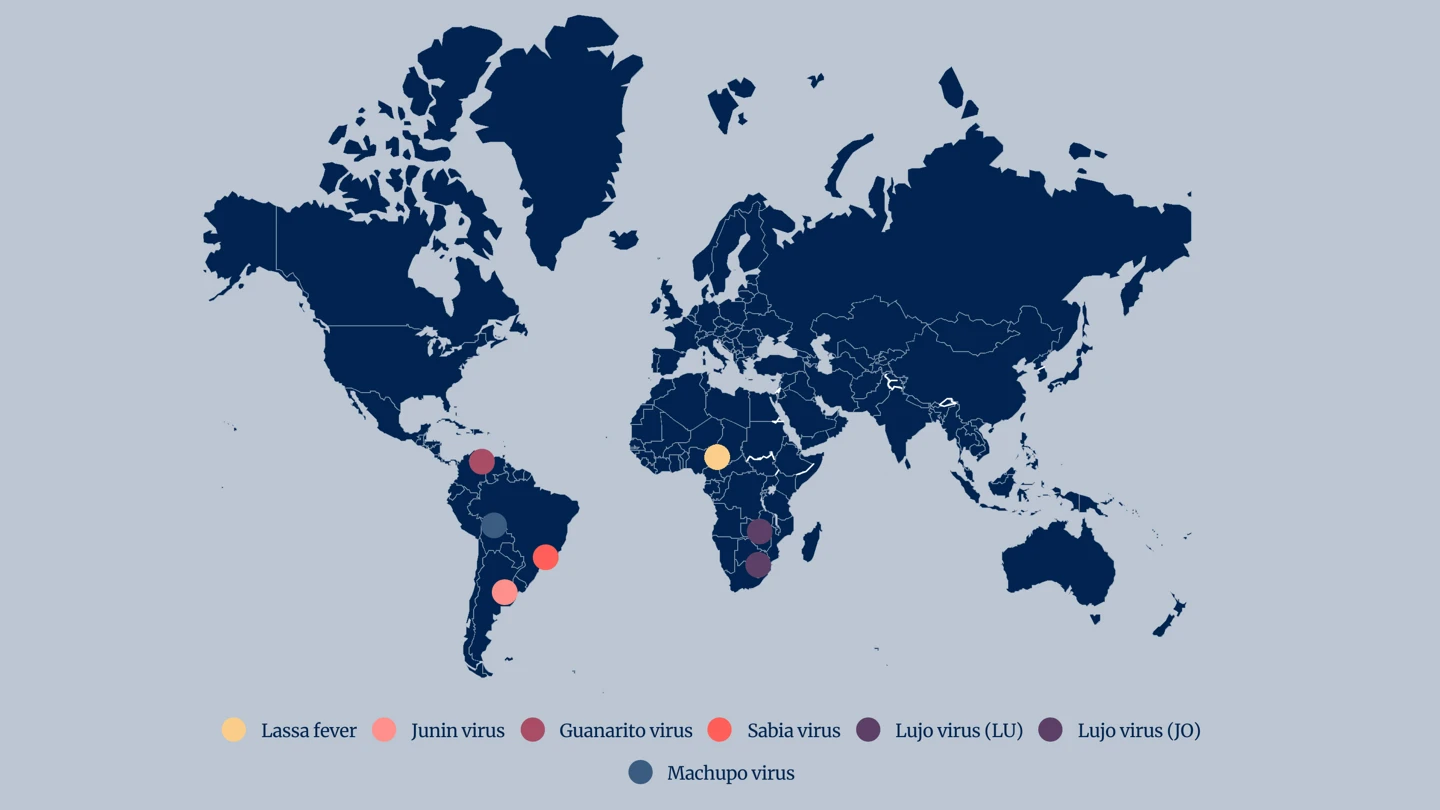

While the family’s human pathogenic viruses are fairly closely related, they are divided into two groups—the Old World Arenaviruses and the New World Arenaviruses.

Prime Suspects

Among the Old World Arenaviruses, Lassa virus, Lujo virus and Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis virus are considered the most worthy of disease detectives’ attention, largely because of their ability to cause severe disease in people.

The prime suspects among the New World Arenaviruses are Junin virus, Machupo virus, Guanarito virus, Sabia virus and Chapare virus.

Nicknames and Aliases

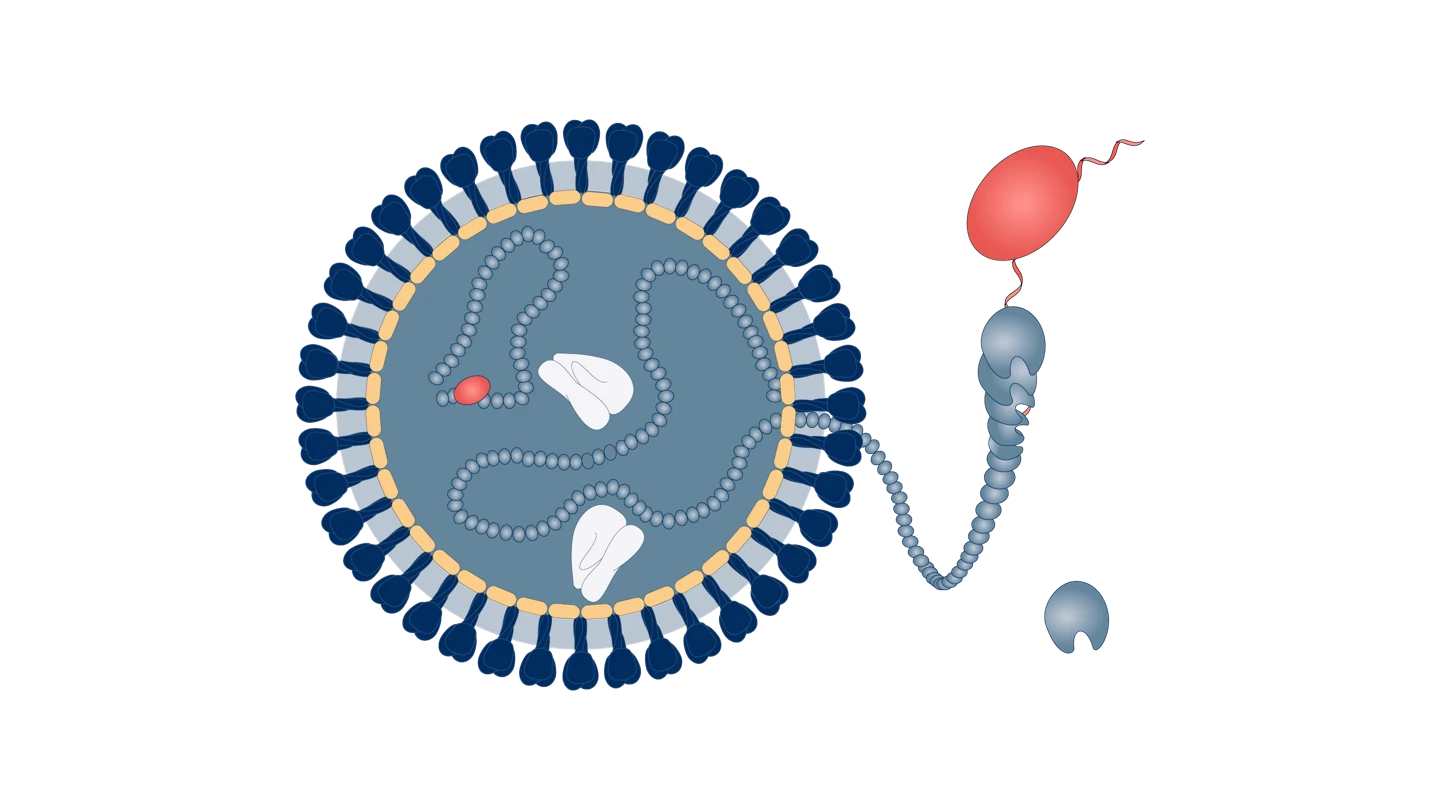

The family name of the Arenaviruses comes from the Latin arenosus, which means ‘sandy’. The name describes the sandy grain-like appearance of Arenavirus particles, or virions, under a microscope.

Lassa virus is named after the small town in Nigeria where it was first identified in 1969.

Junin virus, which takes the name of the city in Argentina where it first emerged in the early 1950s, also goes by the aliases Argentine Haemorrhagic Fever and Argentinian Mammarenavirus, while Machupo Virus is also known as Bolivian Haemorrhagic Fever, Black Typhus or Ordog Fever.

Sabia virus adopted the name of the neighbourhood of Jardim Sabia in Sao Paulo, Brazil, where it was first discovered in 1990. It is also known as Brazilian Haemorrhagic Fever.

Guanarito virus, named after the municipality in Venezuela where it was first detected and identified in 1989, is also sometimes referred to as Guanarito mammarenavirus or Venezuelan Haemorrhagic Fever.

Lujo virus’ name uses the first two letters of the names of the cities involved in the first known outbreak of the disease in 2008—in Lusaka in Zambia and Johannesburg in South Africa.

Distinguishing Features

Arenaviruses are either spherical, oval, or pleomorphic and vary between 110 and 130 nanometers in diameter. They are enveloped, single-stranded RNA viruses encapsulating ‘ribosomes’—minuscule protein factories — which give them a distinctive "sand grain" appearance.

Modus Operandi

Despite multiple intensive studies by disease investigators, the way in which Arenaviruses enter host cells is still something of a mystery. What is known, however, is that the New World Arenaviruses such as Junin and Machupo virus enter human cells after binding to a particular type of molecule known as transferrin receptor 1, or TfR1, and perhaps other types of cell surface receptors too.

Accomplices

Rats, mice, hamsters, voles and other rodents are the primary carriers of Arenaviruses and are the main route of transmission of the viruses from animals to people.

Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus, as one example, is endemic in wild mice and is therefore thought to be a threat to humans wherever wild mice live - which is on every continent of the world except Antarctica.

Machupo virus is carried by a type of mouse - specifically the Calomys callosus, which is commonly known as the large vesper mouse.

Lassa virus is usually spread to people through exposure to food or household items that are contaminated with urine or faeces of infected Mastomys rats. In some regions of West Africa, where Lassa outbreaks are becoming more frequent, Mastomys rats are consumed as food—increasing the risk of disease transmission.

Common Victims

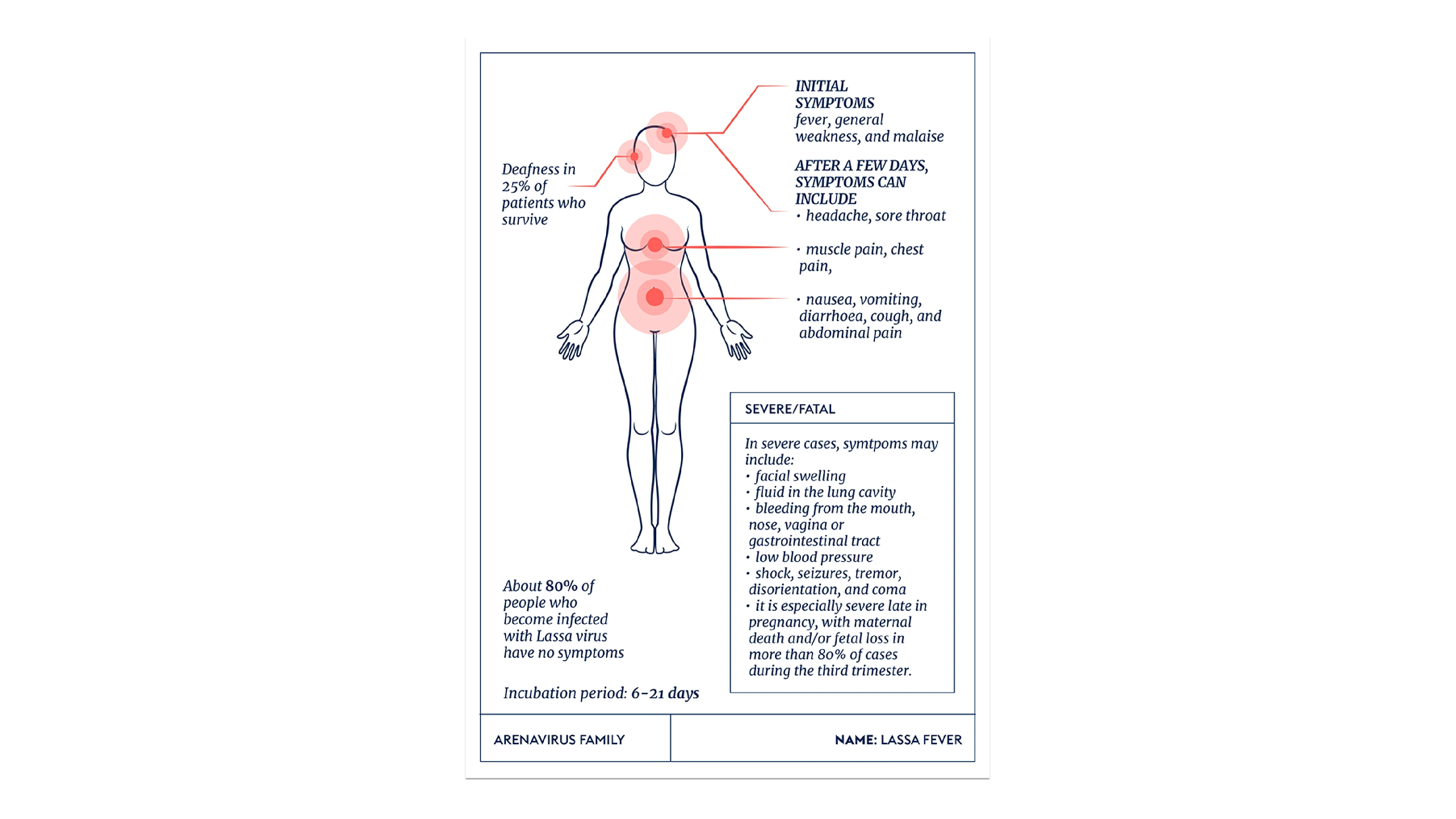

Lassa virus can infect people of all ages, and around 80 percent of people who become infected with the virus have no symptoms, or only mild ones. Around one in five infections, however, develop into severe disease where the virus can affect several major organs such as the liver, spleen and kidneys.

Lassa symptoms in children are similar to those in adults, but Lassa Fever is particularly severe in pregnant women in the third trimester—with the foetus dying in about 95 percent of cases. Newborn Lassa fever infections can lead to a condition known as ‘swollen baby syndrome’, with oedema of the limbs, swelling of the belly, bleeding and sometimes death.

Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus is most commonly recognised as causing neurological disease. It can infect anyone of any gender or race, but young adults are its most common victims, and infection is particularly dangerous in people whose immune systems are weak or compromised in some way.

Investigations have found that most LCMV infections occur during the late autumn and early winter months, when the mice that carry the virus are more likely to move into human homes due to colder weather.

Infamous Outbreaks

Lassa

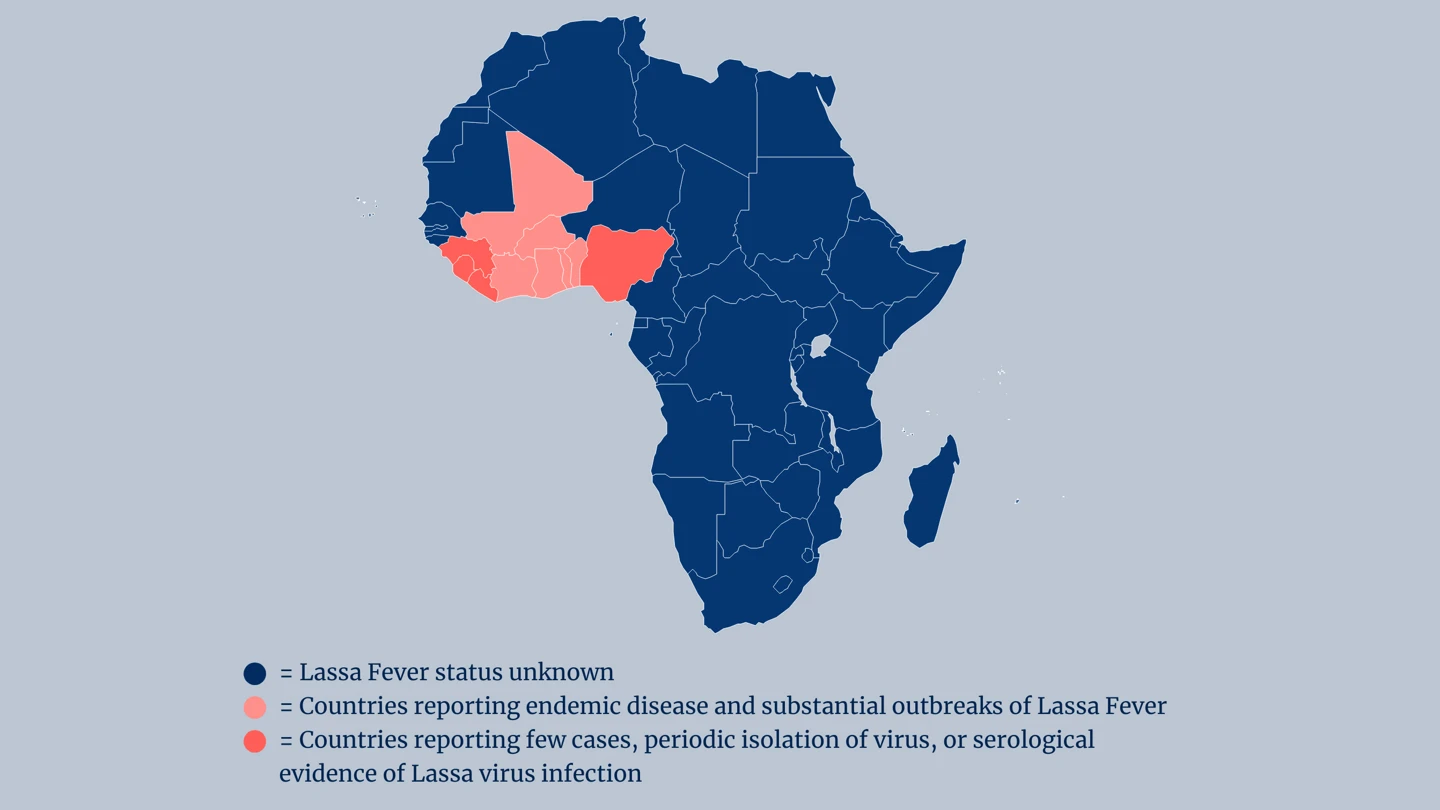

Outbreaks of Lassa virus infection are becoming increasingly regular and increasingly large in West Africa. Outbreaks or sporadic cases have been found across the region, including in Benin, Burkina Faso, Cote d'Ivoire, Guinea, Ghana, Liberia, Mali, Sierra Leone, Togo and Nigeria.

Estimates of the annual number of Lassa virus infections in West Africa range from 100,000 to 300,000. However, these are likely to be underestimates because surveillance for Lassa can be patchy, and confirmed and suspected cases are not always uniformly recorded.

In some areas of Sierra Leone and Liberia, studies have suggested that between 10 and 16 percent of people admitted to hospitals each year have Lassa fever.

Sabia virus

In the case of Sabia virus, to date there have only been a handful of documented human infections worldwide. The first naturally occurring human Sabia Virus case was in 1990, when a female agricultural engineer who was staying in the neighbourhood of Jardim Sabia in Sao Paulo contracted the disease and developed a fatal haemorrhagic fever. A virologist who was studying this first case of Sabia contracted the virus during his research, but survived. Four years later, a researcher in the United States was exposed to Sabia virus in a biohazard facility at Yale University when a centrifuge bottle cracked, leaked, and released aerosolised Sabia Virus particles. He was treated with an antiviral medication called Ribavirin and ultimately recovered from the infection.

Machupo virus

Machupo virus was first discovered in 1959 in an outbreak in San Joaquin in Bolivia. That outbreak lasted more than four years and infected almost 1,000 people, killing more than 250 of them. The deadly outbreak was only contained in 1964 when rat-control measures were brought in.

After a very quiet period between the 1970s and the early 1990s, in which there were no reported human cases of Machupo, the disease struck again in Bolivia in a small outbreak in 1994, infecting nine people and killing seven of them. Then, between 2000 and 2014, there were more than 300 Bolivian cases reported, with at least 22 deaths.

Guanarito virus

From September 1989 until December 2006, the Venezuelan state of Portuguesa recorded 618 cases of Guanarito virus infection in people. Almost all of those infected were people who were working or living in rural areas in the Municipality of Guanarito at the time they become sick. The case-fatality rate was more than 23 percent.

Chapare virus

In early December 2024, a male farmer in Bolivia became infected with Chapare virus and suffered fever, headache, muscle pain, joint pain and bleeding gums before seeking medical help. He died within a few weeks, on December 30, 2024. The World Health Organization confirmed in January 2025 that this case of Chapare haemorrhagic fever was the fifth documented outbreak of the disease in Bolivia and globally since the virus was first identified in 2003.

Common Harms

The Arenavirus family includes some of the most lethal haemorrhagic fevers known. All of its prime suspects can cause life-threatening illness and death.

Among the five known and documented cases of Lujo virus so far, the death rate was 80 percent. The disease initially causes fever, headache and muscle pain, followed by a rash on the face and body, sore throat, neck and facial swelling and diarrhoea. Victims appear to recover slightly, but then deteriorate swiftly into difficulty breathing and circulatory collapse.

Similarly, Sabia virus is highly infectious and causes severe human disease. Since there have only been a handful of human Sabia virus infections reported, information about symptoms has been gathered from only these few. They include fever, headache, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, weakness and very sore throat, as well as conjunctivitis, diarrhoea, stomach pain and bleeding gums.

Most people who become infected with Junin virus also suffer severe illness, and about one in three develop potentially deadly haemorrhagic or neurologic complications. The overall case-fatality rate is around 15 percent.

Lassa fever symptoms include fever, general weakness and malaise, headache, sore throat, muscle pain, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, cough, and abdominal pain. In severe cases, victims suffer facial swelling, fluid in the lung cavity, and bleeding from the mouth, nose, vagina or gastrointestinal tract.

About a quarter of those who survive severe Lassa fever infections develop deafness or partial deafness.

Lines of Enquiry

Disease specialists have pursued multiple lines of investigation against a range of Arenaviruses, and have made reasonable progress against a few of the family’s prime suspects.

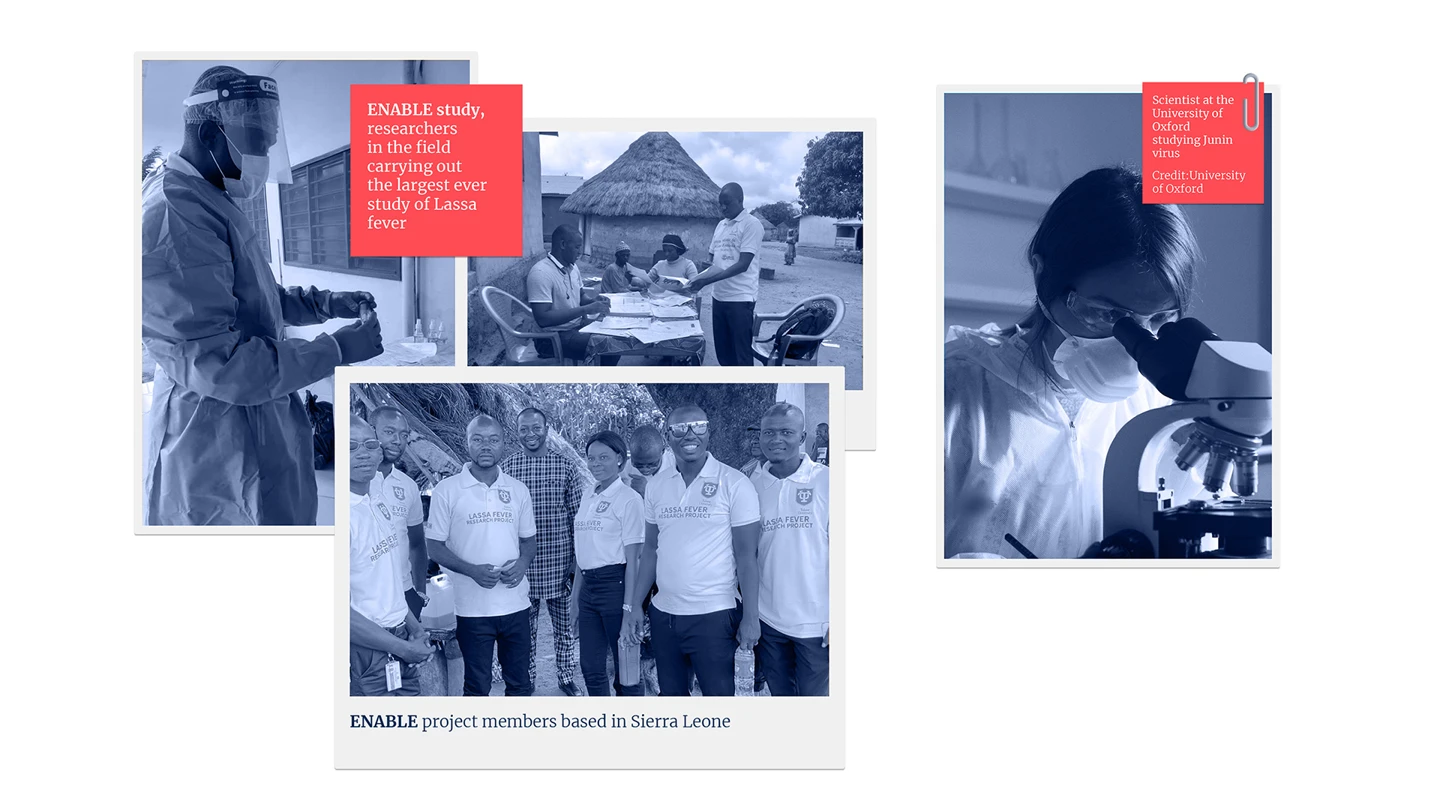

For Lassa fever, CEPI is one of the world’s leading vaccine R&D funders, investing in six potential vaccine candidates to date, of which four have progressed into human testing. One of CEPI’s partners, IAVI, has launched the first-ever Phase II clinical trial of a Lassa vaccine in Abuja, Nigeria.

Working with investigators in Nigeria, Benin, Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, CEPI is also conducting the largest ever multi-country investigation of the epidemiology of Lassa to improve knowledge about the virus and how to counter its attacks.

For Junin virus, a protective vaccine called Candid#1 was developed and licensed for use in Argentina in 2006 and is the only authorised vaccine against any Arenavirus. The vaccine’s use is limited, however, because it is not recommended for children younger than 15, or for pregnant women or people whose immune systems are compromised.

In part because of these limitations, CEPI is supporting the development of a new vaccine candidate against Junin virus using a vaccine platform developed by the University of Oxford that was also used in one of the life-saving Coronavirus vaccines deployed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is hoped that this work will also deepen scientific investigators’ understanding of the optimal vaccine designs and immunological mechanisms that could provide protection against the Junin Virus and may act as an example for vaccine development against other viruses within the Arenavirus family.

Editor's note:

The naming and classification of viruses into various families and sub-families is an ever-evolving and sometimes controversial field of science.

As scientific understanding deepens, viruses currently classified as members of one family may be switched or adopted into another family, or be put into a completely new family of their own.

CEPI’s series on The Viral Most Wanted seeks to reflect the most widespread scientific consensus on viral families and their members, and is cross-referenced with the latest reports by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).

Related articles

Related articles

The Paramyxoviruses

This family contains one of the most contagious human viral diseases, as well as one of the most deadly. Explore The Paramyxoviruses.

Matonaviruses and Togaviruses

Multiple lines of enquiry against Chikungunya virus and its viral relatives are being pursued by scientists around the world, with the hope for a new protective vaccine coming very soon.

The Coronaviruses

Seven members of the Coronavirus family are already known to infect people, often with deadly consequences. Disease investigators fear that more new and dangerous Coronaviruses could spill over at any time.

The Flaviviruses

Yellow Fever is now known as one of several deadly viral haemorrhagic fevers currently classified a Flavivirus, one of The Viral Most Wanted.

The Nairoviruses

The prime suspect in this family is a deadly virus that causes its human victims to bleed profusely.

The Paramyxoviruses

This family contains one of the most contagious human viral diseases, as well as one of the most deadly. Explore The Paramyxoviruses.

The Poxviruses

The viral family of one of the most fearsome contagious diseases in human history

The Hantaviruses

Some Hantaviruses focus their attacks on blood vessels in the lungs, causing the blood to leak out and ultimately ‘drowning’ their victims.

The Retroviruses

The most nefarious Retrovirus—HIV—has infected 85 million and killed 40 million people worldwide.

The Filoviruses

“one of the most lethal infections you can think of” - and it's one whose deadly reach is extending ever further

The Orthomyxoviruses

These viral culprits have caused the deadliest pandemics in human history

The Picornaviruses

Large, persistent and deadly outbreaks of a crippling infection caused by one member of this viral family meant that it was once among the most feared diseases in the world