The Poxviruses

With no cases to remind us, it’s easy to forget the scale and ferocity of Smallpox. It was – is – a truly horrific disease.

The infection is caused by the Variola Virus, which is most often breathed in by its victims. Typically, it starts with a high fever, muscle aches, headaches and vomiting. A few days later, a rash begins to appear on the tongue, mouth and throat in the form of red spots and sores.

Within a day or so, the rash spreads in little bumps to the skin of the face, and then on to the arms, legs, torso and all over the body, including the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. Only then do the disease’s signature pus-filled pustules feature, gradually bursting and scabbing up over the following days.

Those who died of Smallpox usually did so within one to two weeks. In the 20th Century alone, the disease is estimated to have killed between 300 million and 500 million people. Among those it didn’t kill, it left many either blind or horribly disfigured, or both.

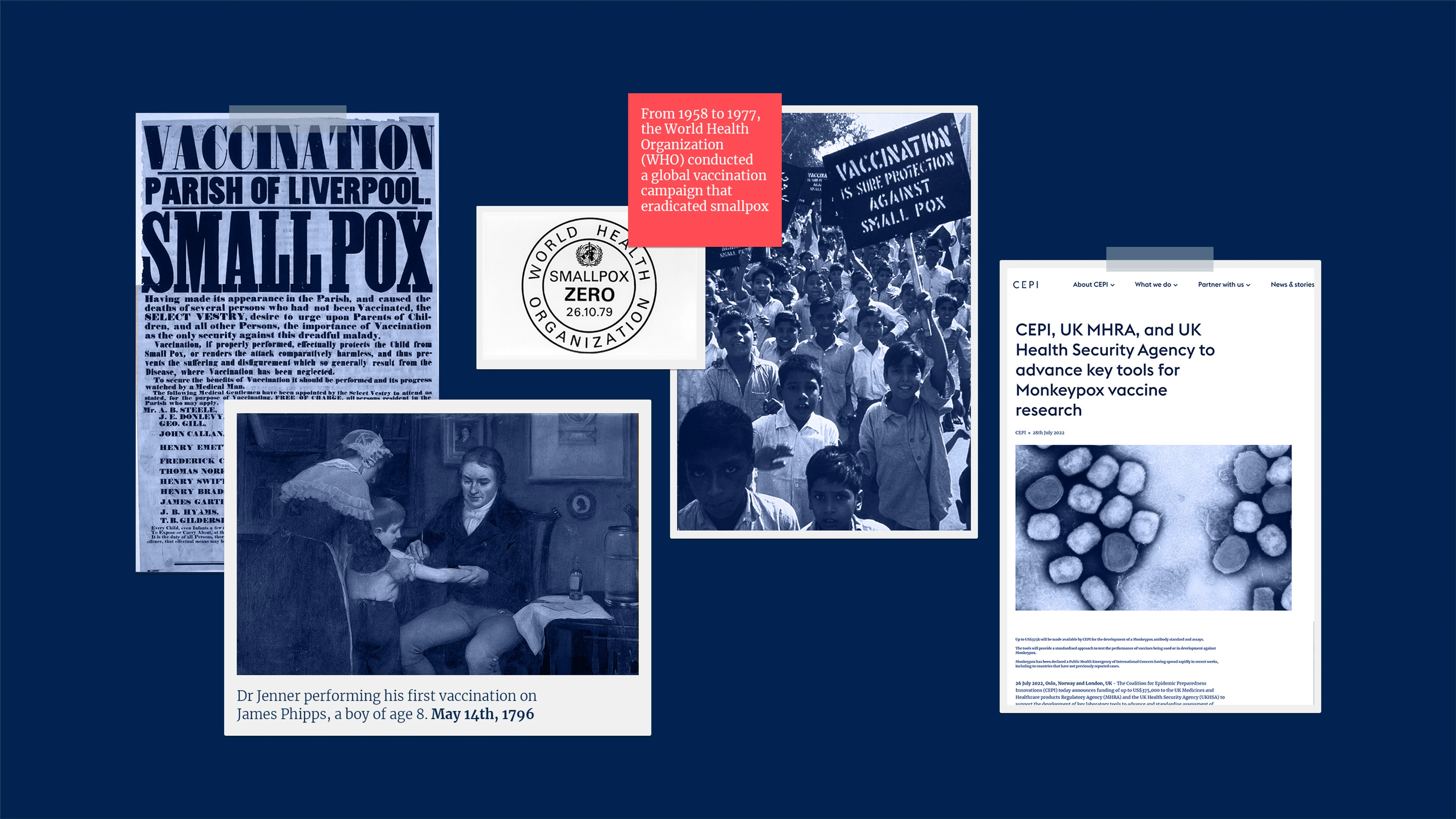

Today Smallpox is known as much for what it can no longer do. It no longer infects, disfigures or kills people in their millions. Thanks to a global vaccination campaign first made possible by the English physician and scientist Edward Jenner more than 200 years ago, Smallpox is the first and - so far - the only human disease ever to have been eradicated.

Unfortunately, however, the Poxvirus family behind the Variola Virus that causes Smallpox has plenty of other menacing members - making this family one of The Viral Most Wanted.

One Big Close-Knit Family?

Yes. The Poxviruses is a large family of more than 70 viruses that are all fairly closely related. Members of this family are divided into a number of subgroups, and they can infect both people and animals. The four Poxvirus family subgroups that are known to pose a risk to human populations are the Orthopoxviruses, the Parapoxviruses, the Molluscipoxviruses and the Yatapoxviruses.

Prime Suspects

The Poxviruses are some of the best known and most feared viruses on earth. The most notorious and deadly suspect within the viral family is Variola, the agent of Smallpox. It and other notable Poxvirus suspects, including Mpox or Monkeypox, Vaccinia and Cowpox, belong to the Orthopoxvirus subgroup.

Within the Parapoxvirus subgroup, prime suspects include Orf Virus, and Pseudocowpoxvirus, while the main ‘one to watch’ within the Molluscipoxvirus subgroup is Molluscum Contagiosum Virus

The Yatapoxvirus subgroup has two notable suspects that can infect humans and primates - Tanapox and Yaba Monkey Tumour Virus.

Nicknames and Aliases

The Poxvirus family name comes from the word pox, which itself derives from the Middle English word ‘pocke’ - or plural ‘pockes’ - meaning pustule, blister or eruptive sore.

Human Monkeypox was given its original name in 1970 after the virus that causes the disease was first discovered in captive monkeys in 1958. But its name was changed in 2022 on advice from the World Health Organization, which renamed it Mpox.

Variola Virus, which causes Smallpox, gets its name from the Latin for ‘spotted’ or ‘speckled’ and refers to the blistering pox that erupt on the skin of its victims.

Orf Virus, which infects sheep, may trace its name’s origin back to an Old English word meaning ‘cattle’. Strangely, it does not naturally infect cattle, but is largely found in sheep and goats.

In the Yatapoxvirus subgroup of the Poxvirus Family, Tanapox is named after the Tana River Basin in Kenya where it was first identified, while Yaba Monkey Tumour Virus is named after the Yaba suburb of the city of Lagos in Nigeria where it was discovered in some captive rhesus monkeys in the late 1950s.

Distinguishing Features

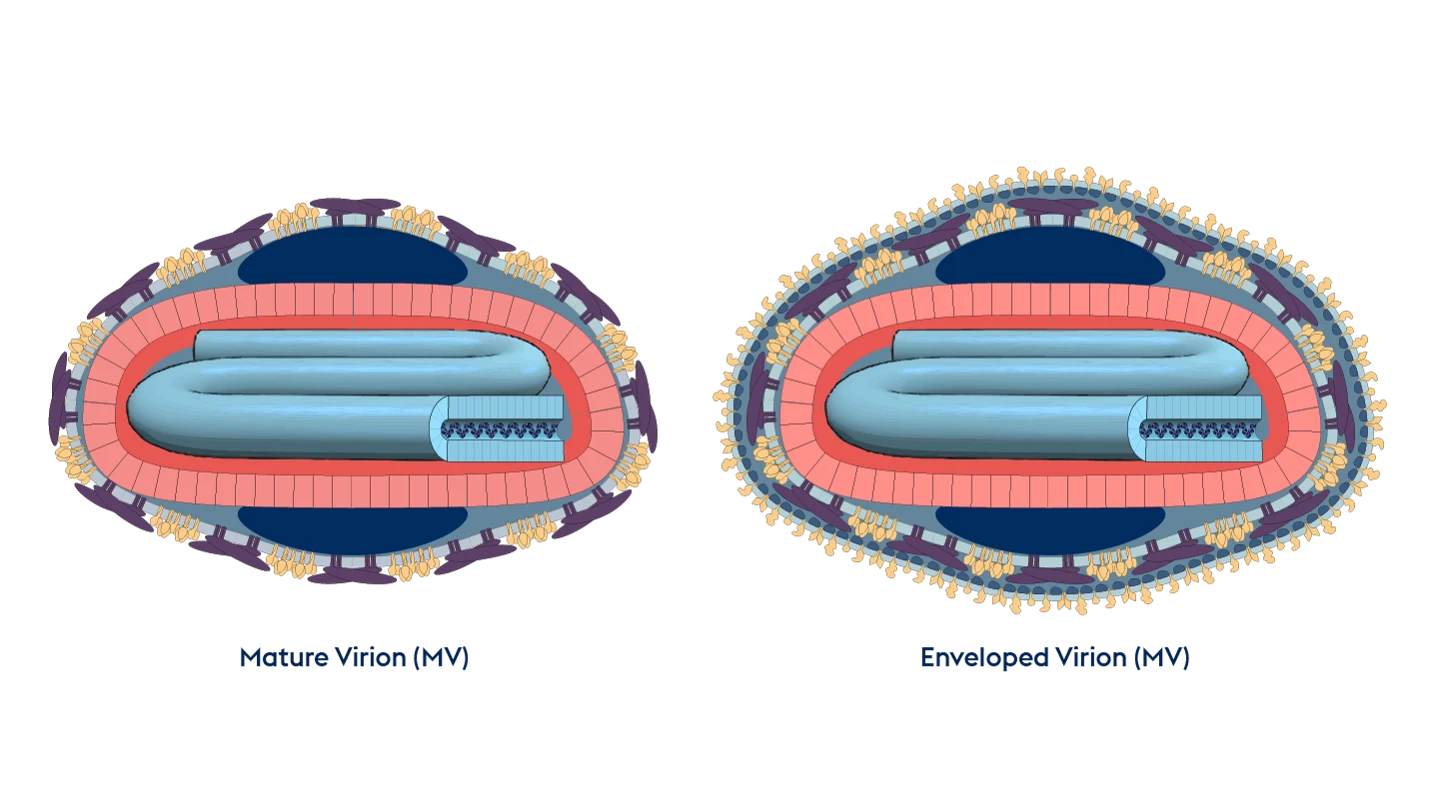

Poxviruses are the among largest and most complex known viruses. They are generally oval or brick-shaped viruses, between 220 and 450 nanometres long, and have an intricate internal structure, including a double-stranded DNA genome and multiple enzymes and proteins.

Modus Operandi

The M.O. of Poxviruses is complex and unique to this particular viral family. Unlike other DNA viruses, members of the Poxvirus Family replicate in the cytoplasm of host cells, rather than in the nucleus. The attachment of the virus to a host cell prompts a sequence of events in which the viral DNA initially replicates using its own proteins, then captures the host cell machinery to reproduce and coat itself in the host’s proteins, before proceeding to infect other cells. This clever enveloping of itself with host proteins means the Poxvirus creates a ‘cloak’ to enable it avoid detection by, and hence evade, the host’s immune defences.

Accomplices

Poxviruses can spread from person to person without the need for intermediate hosts and by any one of a number of routes. The Smallpox-causing Variola Virus, for example, is highly contagious and spreads in aerosols and droplets in the breath, coughs and sneezes of someone who is infected.

Molluscum Contagiosum Virus is spread from one person to another via skin contact. It can also spread within and around a single infected person’s body if they scratch the spots and then touch another area.

Other members of the Poxvirus family, such as the Orf Virus that primarily infects sheep, can get in through the skin via tiny cuts or grazes.

Poxviruses are also infamously robust and stable - meaning they are not generally weakened or killed by exposure to normal temperatures and environments. These attributes make them also able to survive for long periods - even several years - on surfaces or in the dried scabs of previous victims.

Common Victims

While many members of the Poxvirus family infect a range of animals - from cows, sheep deer and buffalo, to camels, monkeys and seals - Variola Virus and Molluscum Contagiosum Virus are specific to humans and only infect people.

Before it was wiped out, Smallpox could infect everyone and anyone, from adults to children to babies. Historical evidence suggests, however, that babies and young children were most at risk of becoming fatal victims. Before vaccination began and eventually eradicated the disease, more than 90 percent of smallpox deaths were in children under 10 years old.

Mpox is increasingly spreading in people and is seen as a significant epidemic threat despite originally being a disease whose victims were usually monkeys. In an ongoing Mpox outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo which started in 2023 and is caused by a strain of the virus known as Clade I, the vast majority of victims of infection and death have been children younger than 15 years.

The most common victims of the Orf Virus, from the family’s Parapoxvirus subgroup, are sheep and goats. But it has also been known in rare cases to infect people. Those most at risk are farmers, vets and other people who work closely with sheep or goats.

Infamous Outbreaks

Smallpox

Smallpox ravaged the world for many centuries before disease detectives finally began to make headway against it with the development of vaccination. The earliest physical evidence of Smallpox infection was found in Egyptian mummified bodies of people who died around 3,000 years ago, although disease investigators think the Variola Virus that causes it could well have emerged many centuries before that.

Britain suffered repeated deadly outbreaks of Smallpox during the 17th Century, including one that claimed the life of Queen Mary II of England, who fell victim to the disease in 1694 when she was 32 years old. Historical accounts from the 18th Century show that Smallpox killed an estimated 400,000 Europeans every year during this period. Among its most famous European victims were five reigning monarchs - Joseph I of Germany, Peter II of Russia, Louis XV of France, William II of Orange, and the last Elector of Bavaria.

Estimates for the whole of the 20th Century - even when Smallpox vaccination had been introduced and the disease had already been eliminated in North America and in Europe - suggest that it still killed between 300 and 500 million people worldwide.

With a massive and ultimately decades-long global vaccination campaign that began with the first immunisations in the 18th Century, disease fighters eventually managed to put an end to outbreaks of Smallpox in the 1970s. The last naturally occurring case of infection was in Somalia in 1977, and the World Health Organization officially declared the world Smallpox-free in 1980. This viral killer remains the only human disease in history to have been totally eradicated.

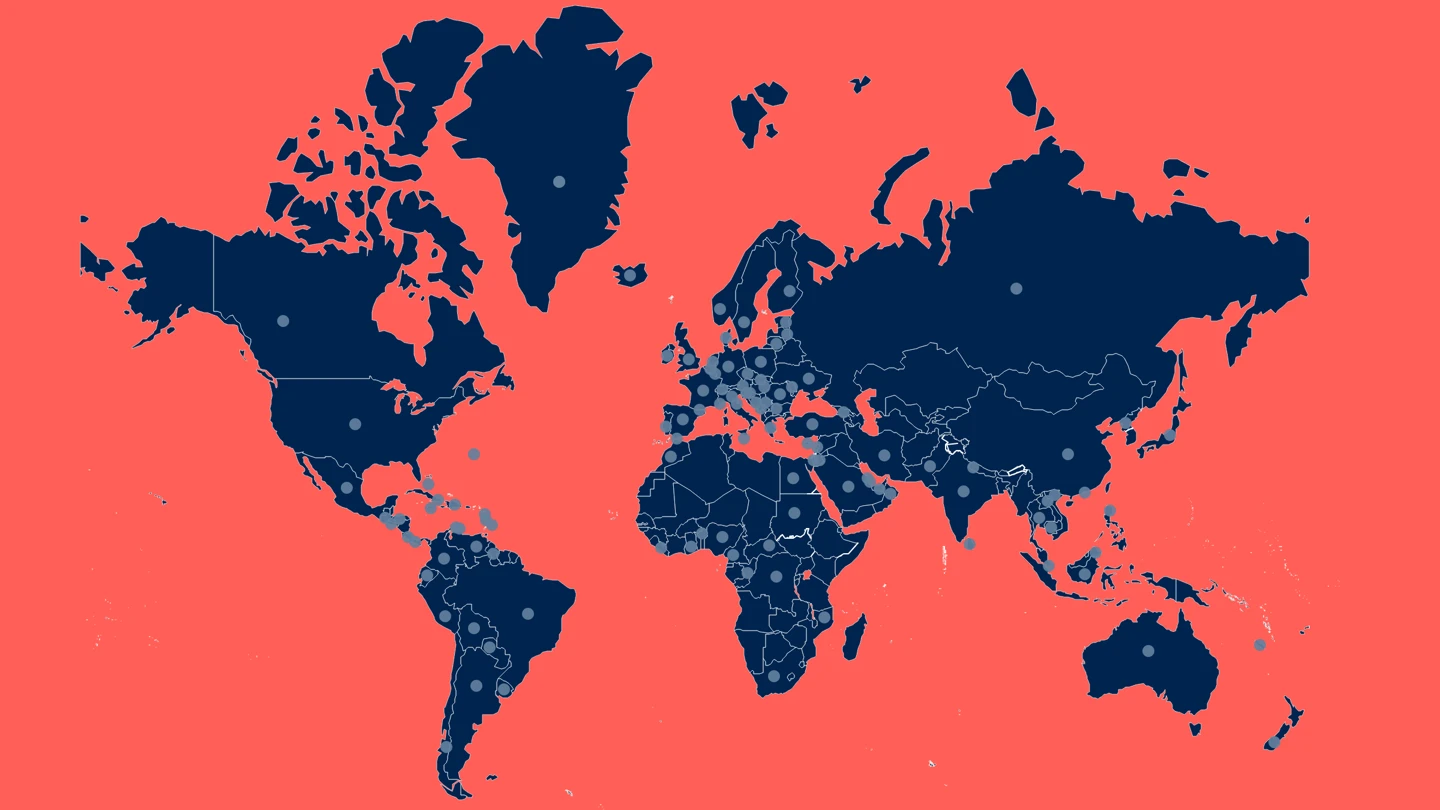

2022-2023 Mpox Outbreak Global Map - US CDC data, updated March 2024

Mpox

Mpox has, since its first detection in people in 1970, staged sporadic attacks across Central, East and West Africa, with people in the Democratic Republic of the Congo frequently falling victim to the disease. Every year since 2005, thousands of suspected and confirmed Mpox cases have been reported in the DRC.

In 2017, Mpox re-emerged in Nigeria, West Africa’s most populous country, and has continued to spread between people across the country, as well as across borders into neighbouring countries.

By far the largest outbreak of Mpox ever recorded began in May 2022, when the Clade II strain of Mpox virus appeared to erupt suddenly in Europe before spreading rapidly across the world. The epidemic affected at least 110 countries, with 87 thousand reported cases, at least 112 of which were fatal. Disease investigators noted that this global Mpox outbreak primarily affected gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. Epidemiological analysis of the outbreak found that the Mpox virus had often spread person-to-person through sexual networks.

Another large and deadly outbreak of Mpox – this time caused by the Clade I strain - has been spreading in the Democratic Republic of Congo since 2023. Official figures show there were more than 14,600 Mpox infections and 901 deaths in DRC in 2023 alone – almost three times the numbers reported in the previous year. The majority of the Mpox cases and almost three-quarters of the Mpox deaths in 2023 in the DRC were among children under 15.

Common Harms

The most prominent feature of both human and animal infections with any member of the Poxvirus family is skin lesions, blisters or pus-filled sores. These vary in number, size and appearance according to which of the Poxviruses is causing the disease. People infected with Mpox, for example, can have as few as one or two lesions on the skin, or up to several thousand, and these are generally smallish pearly-coloured papules. The Variola Virus behind Smallpox, on the other hand, causes large, encrusted pustules.

Besides these sores and blisters, other common initial symptoms of a Poxvirus attack include fevers and headaches.

Smallpox is also known not only for its very high death rate, but for its very high rate of disfiguring complications in victims who survive. Many Smallpox survivors are left with permanent and deep pox scars over large areas of their bodies, in particular on their faces. Some are also rendered blind by the disease.

Lines of Enquiry

While the Poxvirus family is responsible for one of the most fearsome contagious diseases in human history, it is also responsible for one of the most important advances in modern medicine - vaccination. Today, vaccines are recognised as having saved more human lives than any other medical invention in history.

It was thanks to doctors and scientists pursuing multiple lines of enquiry against Smallpox that the theory, and then practice, was developed that forewarning the body’s immune system with a similar pathogen or very small amount of the same pathogen would prompt it to mount an effective defence against that pathogen in future.

The earliest immunisation strategy devised to defend people against Smallpox used the Variola Virus itself as the inoculating agent and was known as Variolation.

Around half a century later, in 1789, the scientist Edward Jenner developed a much safer practice by showing that another pathogen from the Poxvirus family - Cowpox Virus - could be used to prevent Smallpox infections in people. This was the procedure that disease detectives called vaccination - a name derived from ‘vacca’, the Latin word for cow.

These historic and successful lines of enquiry were also pivotal for scientific investigators to pursue and advance many other areas of human physiology and medicine, in particular cell biology, immunology and vaccinology against multiple diseases.

The success of Smallpox vaccines also led to the recognition of the possibility that immunisation might in some cases be capable of defending people against more than one viral disease at a time - if those viruses are related via the same viral family. This is known as cross-protection - a feature that has meant that the development of a vaccine against Smallpox in the 18th Century has led to people being able to be protected with the same vaccine against Mpox and other Poxvirus diseases.

Several research groups are also pursuing the development of new Mpox vaccines - including ones based on mRNA and DNA vaccine technology - looking for ways to make them faster and/or cheaper to produce and therefore more swiftly and widely accessible.

When the global Mpox outbreak of 2022 was declared a Public Health Emergency by the World Health Organization, CEPI joined forces with several partners to fund the development of an antibody standard and assays - important laboratory tools used to standardise the assessment of Mpox vaccines.

In September 2023, CEPI partnered with the German biotech company BioNTech to begin early-stage human trials of its Mpox vaccine, BNT166, which uses mRNA technology.

Editor's note:

The naming and classification of viruses into various families and sub-families is an ever-evolving and sometimes controversial field of science.

As scientific understanding deepens, viruses currently classified as members of one family may be switched or adopted into another family, or be put into a completely new family of their own.

CEPI’s series on The Viral Most Wanted seeks to reflect the most widespread scientific consensus on viral families and their members, and is cross-referenced with the latest reports by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).

More in the series

More in the series

The Arenaviruses

The Arenavirus family includes some of the most lethal haemorrhagic fevers known. All its prime suspects can cause life-threatening disease and death

The Coronaviruses

Seven members of the Coronavirus family are already known to infect people, often with deadly consequences. Disease investigators fear that more new and dangerous Coronaviruses could spill over at any time.

The Flaviviruses

Yellow Fever is now known as one of several deadly viral haemorrhagic fevers currently classified a Flavivirus, one of The Viral Most Wanted.

The Filoviruses

“one of the most lethal infections you can think of” - and it's one whose deadly reach is extending ever further

The Flaviviruses

Yellow Fever is now known as one of several deadly viral haemorrhagic fevers currently classified a Flavivirus, one of The Viral Most Wanted.

The Hantaviruses

Some Hantaviruses focus their attacks on blood vessels in the lungs, causing the blood to leak out and ultimately ‘drowning’ their victims.

Matonaviruses and Togaviruses

Multiple lines of enquiry against Chikungunya virus and its viral relatives are being pursued by scientists around the world, with the hope for a new protective vaccine coming very soon.

The Nairoviruses

The prime suspect in this family is a deadly virus that causes its human victims to bleed profusely.

The Orthomyxoviruses

These viral culprits have caused the deadliest pandemics in human history

The Paramyxoviruses

This family contains one of the most contagious human viral diseases, as well as one of the most deadly. Explore The Paramyxoviruses.

The Phenuiviruses

The most infamous Phenuivirus, Rift Valley fever, poses a significant threat to people and livestock causing serious disease and dangerous outbreaks.

The Picornaviruses

Large, persistent and deadly outbreaks of a crippling infection caused by one member of this viral family meant that it was once among the most feared diseases in the world