Rift Valley fever

Rift Valley fever is a disease whose epidemic potential lies in the intersection of global climate, trade and health security. CEPI invests in a range of research programmes aiming to address the threat.

What is Rift Valley fever?

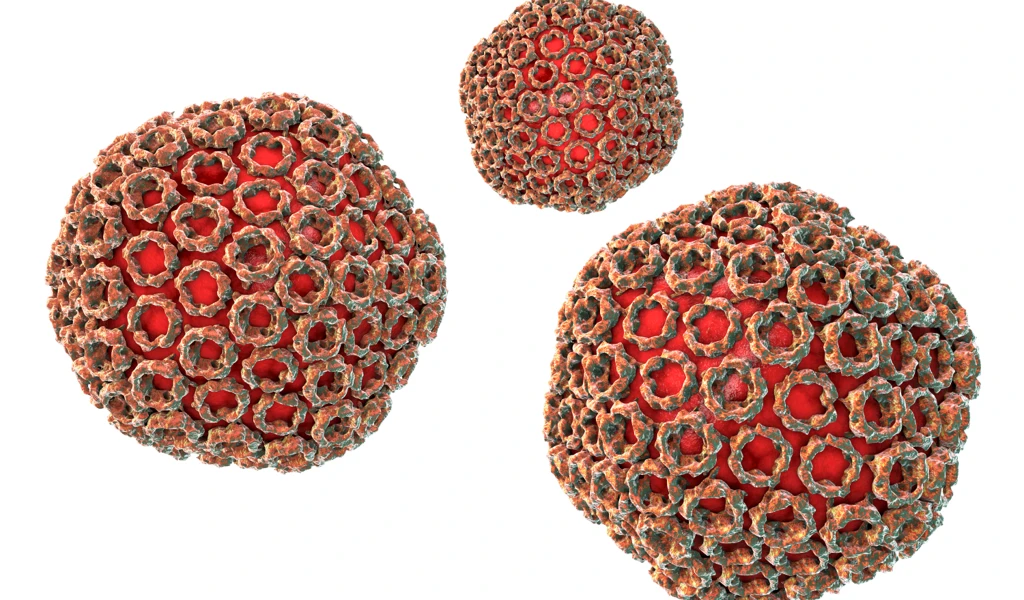

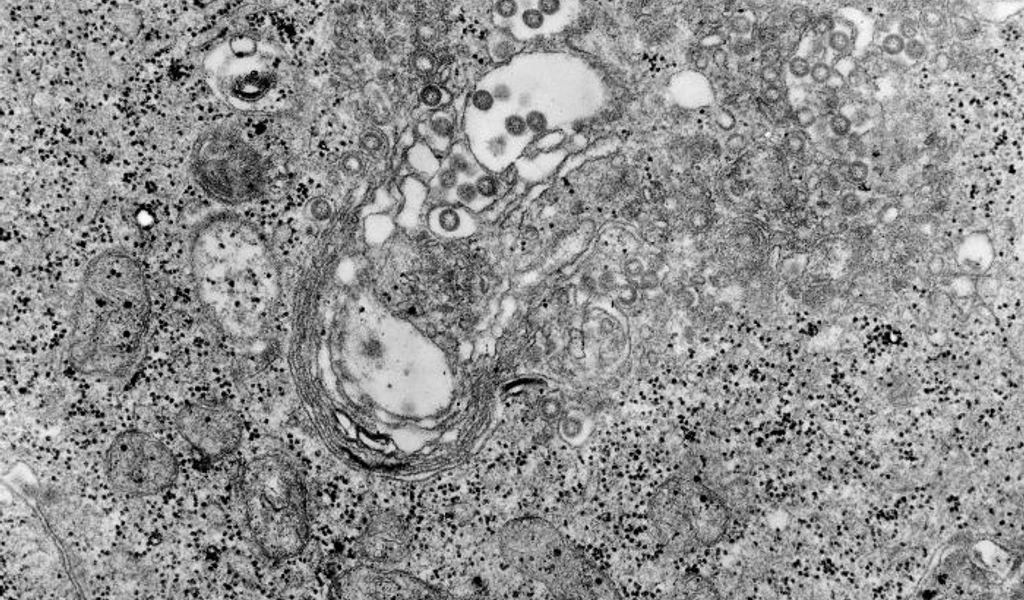

Rift Valley fever is a potentially deadly disease caused by the Rift Valley fever virus, which is part of the Phenuivirus family.

It most commonly affects domestic animals, such as cattle, sheep, goats and camels. However, Rift Valley fever can also cause infection and outbreaks in people if they are bitten by infected mosquitoes or blood-feeding flies. Infection can also occur if people come into contact with infected animal fluids or tissues, such as during butchering, veterinary procedures, or when consuming raw or undercooked animal products.

30+

Number of countries where Rift Valley fever has been identified

~600

Estimated human deaths during one outbreak in Egypt in 1977

50%

Fatality rate in those who develop severe Rift Valley fever disease

Where does Rift Valley fever occur?

Rift Valley fever was first identified in 1930, when sudden deaths and abortions were reported in sheep in Kenya's Rift Valley.

Since then, multiple outbreaks have been reported across Africa and the disease has since spread to the Middle East. A 1977 outbreak in Egypt infected 20,000 to 40,000 people and 600 people died. Twenty years later, a major outbreak in East Africa infected 90,000 people and 500 people died.

An outbreak is currently affecting people and livestock in Senegal and Mauritania in West Africa, and animals in The Gambia and South Africa.

A CEPI-sponsored review of Rift Valley fever's spread over the past two decades found that the virus has expanded in both range and frequency. CEPI is now supporting research to track the disease burden and impact of Rift Valley fever across Africa.

As climate change persists, expanding the range of mosquitoes and increasing the likelihood of extreme weather events such as flooding, there is a risk that this trend will continue.

What are the symptoms of Rift Valley fever?

People with Rift Valley fever usually show no symptoms or develop mild symptoms like fever, weakness and muscle pain.

Though most people with Rift Valley fever recover within a week, severe complications develop in 8-10% of people infected.

However, in some cases, it can progress to haemorrhagic fever - bleeding from multiple body parts - and inflammation of the brain and eyes, resulting in blindness.

In those who develop the haemorrhagic form of the disease, the fatality rate is around 50%.

In livestock, Rift Valley fever causes fever, weakness, abortions and a high rate of severe illness and death, particularly among young animals. Rift Valley fever can therefore cause significant economic damage in pastoral farming communities due to the loss of infected livestock pushing people into deprivation and impacting their mental wellbeing.

How is CEPI responding to Rift Valley fever?

Rift Valley fever vaccines have been used successfully to protect livestock. However, there are no vaccines currently approved to protect people.

CEPI has supported the development of four human Rift Valley fever vaccine candidates. This includes funding the first Phase II clinical trial of a human Rift Valley fever vaccine in an outbreak-prone area. The research is ongoing in Kenya.

We have also joined forces with two major collaborative research groups to strengthen scientific understanding of Rift Valley fever and its disease impact across Africa. Led by institutions in Kenya and Tanzania the CEPI-funded research will help guide the planning of future clinical trials assessing human Rift Valley fever vaccine candidates.

CEPI will work with developers, partners and countries affected by Rift Valley fever to ensure this work is a success and vaccines are made available to those who need them.

Related news

Landmark African-led research to map the extent of Rift Valley fever impact

A plan to protect lives and livelihoods from a mosquito-borne killer

South Africa’s Afrigen to develop human mRNA Rift Valley fever vaccine

Promising human Rift Valley fever vaccine to enter Phase II clinical trials in Kenya

CEPI partners with University of California, Davis to advance a vaccine against potentially deadly Rift Valley fever virus into clinical trials

Rift Valley fever vaccines to advance with new $50 million CEPI and EU funding call

Efforts to advance Rift Valley fever vaccines progress with new CEPI partnership

CEPI awards funding agreement worth up to US$9.5 million to Colorado State University to develop a human vaccine against Rift Valley fever

How CEPI is preparing to combat Rift Valley fever

CEPI awards contract worth up to US$12.5 million to consortium led by Wageningen Bioveterinary Research to develop a human vaccine against Rift Valley fever