The Hantaviruses

The Albuquerque Journal, a newspaper in the U.S. state of New Mexico, ran an alarming headline in its May 27th edition in 1993: “MYSTERY FLU KILLS 6 IN TRIBAL AREA”. The article told a story that had first come to light two weeks earlier, when a 19-year-old man was rushed to the emergency department of the Indian Medical Centre in Gallup.

The man, a Native American from the Navajo tribe, had been travelling with his family to his fiancée’s funeral when he began struggling to breathe in the car’s back seat. The family veered off the road to call for an ambulance. Both the first responders and, later, the emergency room doctors tried to revive the victim with cardiopulmonary resuscitation, but their efforts were in vain. The young man’s lungs were flooded with fluid. He had effectively drowned.

The ER doctors were shocked, not only at the speed and dramatic nature of the man’s death, but by the similarity of the case to that of a young woman a few weeks earlier who had suffered the same symptoms and also died.

Over the next few weeks, more than a dozen more people in the area contracted the deadly disease, many of them young Navajos.

During the same period, doctors and public health officials tried desperately to identify what was causing the outbreak. On June 11th, 1993, the weekly Morbidity And Mortality report from the U.S. Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) revealed that the mystery pathogen was “a previously unrecognized Hantavirus”.

The novel viral villain belonged to the Hantavirus family—a group of viruses normally carried by rats, mice and other rodents and known to cause severe disease in people. The Hantavirus family is one of The Viral Most Wanted.

One Big Close-Knit Family?

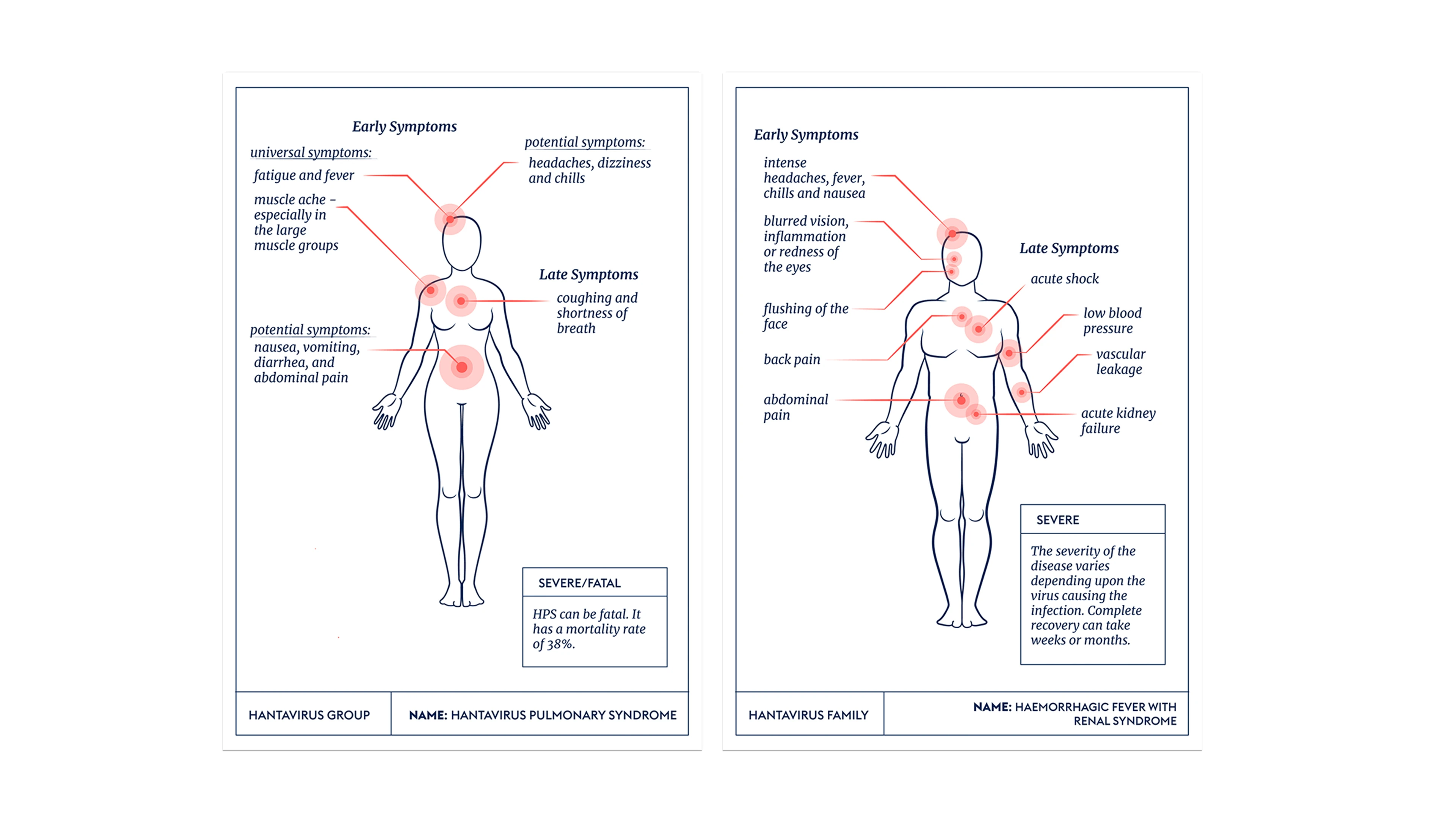

Yes, the Hantavirus Family is a fairly close-knit group of viruses, many of which can cause various diseases and syndromes in people all across the world. The family has two distinct subgroups: the Old World Hantaviruses, found in Africa, Asia and Europe; and the New World Hantaviruses, found in the Americas. While the two subgroups are related, they are also distinct in that they cause very different types of illness in their human victims. Viruses in the New World subgroup cause a disease known as Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome, or HPS, while viruses in the Old World subgroup cause a disease known as Haemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome, or HFRS.

Prime Suspects

In causing disease and death in the Americas, the most notorious suspects from the Hantavirus family are Sin Nombre Virus and Andes Virus, both of which are members of the New World Hantavirus subgroup. Other notable culprits in the Hantavirus family are Seoul Virus, Hantaan Virus, Dobrava Virus, Puumala Virus and Saaremaa Virus, all of which belong to the Old World subgroup.

Nicknames and Aliases

Ironically, it is the Hantavirus currently known as Sin Nombre Virus—the Spanish for “the virus with no name”—that has gone through the most name changes and had the most aliases. Originally referred to as Four Corners Virus, the novel Hantavirus that was identified in the 1993 New Mexico outbreak, described above, took its first name from the region where it originally emerged. The U.S. states of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah and Colorado come together at Four Corners. At times, this novel Hantavirus was also nicknamed Convict Creek Virus and known by the alias Muerto Canyon Virus before it acquired its current title of Sin Nombre Virus.

Many of the Old World Hantaviruses get their names from the places they were first identified. Hantaan Virus, for example, is named after the Hantaan River in South Korea where it was first found, while Seoul Virus takes its name from the South Korean capital city. Puumala Virus has the name of an area of Finland where it was discovered in 1980, while Saaremaa Virus is named after an island on the west coast of Estonia. Dobrova Virus is known by the name of the village in southeastern Slovenia, where it was found in the mid-1980s.

Distinguishing Features

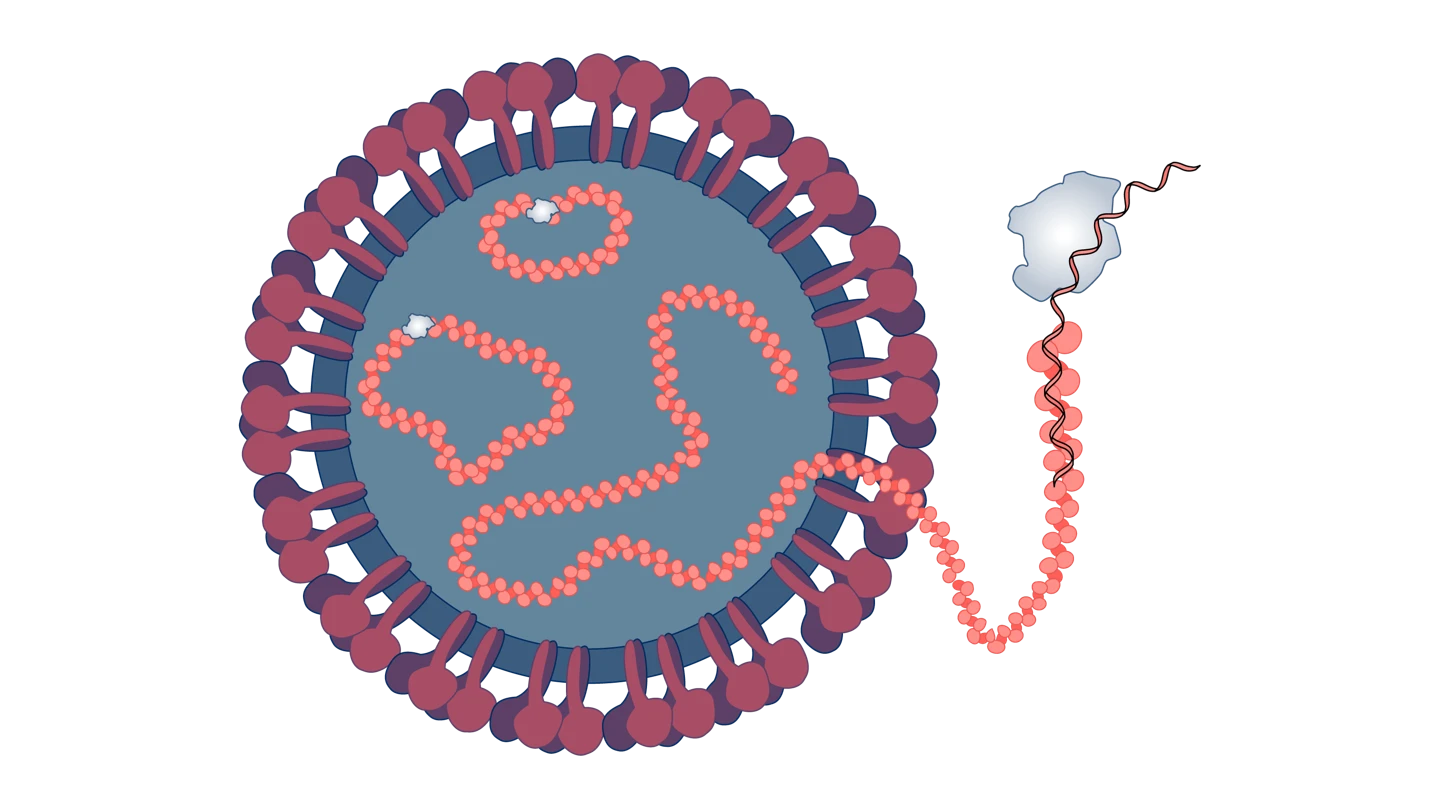

Hantaviruses are enveloped viruses with a genome that consists of three single-stranded RNA segments. The viral particles, or virions, from members of this family are spherical or ovoid with an average diameter of between 80 and 120 nanometres. Their surface structure features a grid-like pattern which is formed by glycoprotein projections anchored in a double-layered fatty membrane coating, or envelope. The virions are notorious for being very stable and for being able to survive for 10 days at room temperature and at least 18 days at very low temperatures - down to minus 20 degrees Celsius

Source: Viral Zone by SwissBioPics

Modus Operandi

Hantaviruses infect their human victims by attaching to specific proteins, or receptors, in specific types of the host’s cells. Members of this viral family are known for their preference for infecting endothelial cells—the type that line the blood vessels—in a variety of organs in the human body, including the lungs, heart, kidney, liver and spleen.

Accomplices

The Hantavirus family is known to have a whole range of accomplices, with each viral family member having one or two specific species of rodents acting as its spreading agent. The chief partner-in-crime of Sin Nombre Virus is the North American deer mouse—otherwise known as Peromyscus maniculatus. For Seoul Virus, the natural hosts are Rattus Norvegicus—a.k.a the Norway rat—and the black rat, or Rattus rattus.

Dobrava Virus is carried by a rodent called the yellow-necked mouse, and Saaremaa Virus uses the striped field mouse as its main accomplice. Puumala Virus is carried by a rodent known as a bank vole, and Andes Virus is carried by the long-tail pygmy rice rat.

The Hantavirus family’s rodent accomplices do not get sick from the virus themselves, which makes them very efficient at spreading the virus wherever they live and forage. The virus is excreted in their urine, faeces and saliva, tiny particles or droplets of which can contaminate the air in their surroundings and be inhaled by people close by. On rare occasions, people can become infected with a Hantavirus after being bitten by a rodent carrier.

Common Victims

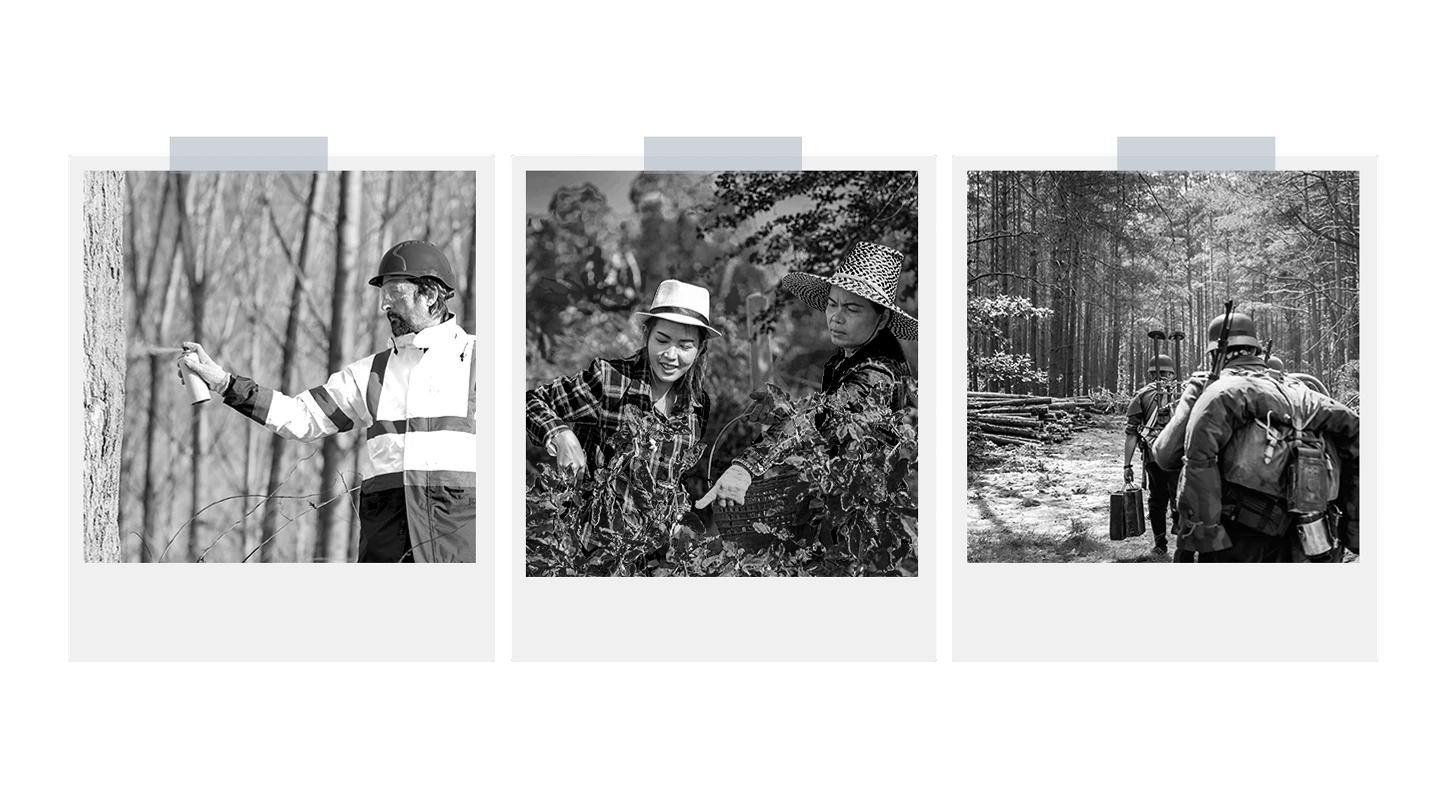

Hantaviruses can infect people of any age, gender or ethnicity, but those most at risk are people who work or live in environments where the Hantavirus rodent accomplices are most prolific. This means that people who work in occupations such as forestry, farming, trapping or the military are among those with the highest risk of falling victim to a viral attack by a member of the Hantavirus family. The geographical distribution of the rodent accomplices is also a factor in determining who might be at highest risk. For example, Dobrava Virus—which is carried by the yellow-necked mouse—is found only in south-east Europe as far as the Czech Republic and southernmost Germany in the north, even though its accomplice species has a far wider distribution within Europe.

Infamous Outbreaks

Haemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome

The vast majority of outbreaks of Haemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome (HFRS) are in Asia, particularly China, where the disease is caused mostly by Hantaan Virus during winter months, and mostly by Seoul Virus in the spring months, when outbreaks tend to be larger. Since the first clinical HFRS case was detected in mainland China in 1931, China has gradually become the most prevalent country in the world, with almost 210,000 cases of HFRS and 1,855 deaths reported between 2004 and 2019. This toll accounted for more than 90 percent of all HRFS cases worldwide during that 15-year period.

Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome

Outbreaks of Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS), the other potentially deadly infection caused by members of the Hantavirus family, generally erupt in South and North America.

Two years after the first known outbreak of HPS was discovered in 1993 to have been caused by the novel Sin Nombre Virus, Paraguay also suffered a serious HPS outbreak. The epidemic was later found to also have been caused by Sin Nombre Virus with Hantavirus-spreading Vesper mice acting as accomplices.

The following year, 1996, there was another notable cluster of cases of HPS in Argentina. Disease detectives analysing this epidemic—which claimed victims in three different cities in southern Argentina and lasted 11 weeks—found the viral attacker behind the HPS infections was Andes Virus. The southern Argentinian HPS outbreak also became known for providing disease investigators with the first reliable evidence for person-to-person transmission of a Hantavirus.

Common Harms

Both of the major diseases caused by Hantavirus family members can be severe and sometimes fatal in people, but can also cause relatively mild symptoms that are similar to flu. Recorded death rates for Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome have reached as high as 50 to 60 percent in some epidemics, and for Haemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome as high as 12 to 15 percent.

Initial signs of a Hantavirus attack tend to be similar, whether the culprit is an Old World or a New World virus. Often starting with a fever, body aches and sometimes vomiting, the infections are not immediately easy to distinguish from other infectious diseases in the early stages.

Beyond these initial stages, however, the two types of infection become quite distinct. Hantaviruses from the New World—Sin Nombre Virus and Andes Virus, for example—focus their attacks on the lungs. There they can infect cells that line the tiny blood vessels and cause them to become “leaky”, ultimately flooding the lungs with fluid and causing the victim to struggle for breath. When these viruses reach the heart, the damage they inflict limits its ability to pump blood around the body. This failure causes acutely low blood pressure—a symptom also known as going into shock—because many of the body’s cells become starved of oxygen. This can lead to the failure of most or all of the body’s organs and rapidly cause death.

With HFRS infections caused by Old World Hantaviruses, the second phase of symptoms can include flushed cheeks, rash and red or sore eyes. Because these viral attacks cause internal bleeding - or haemorrhaging - severe symptoms can include low blood pressure, shock, and acute kidney failure. Analysis by disease experts suggests that the severity of the disease can vary depending upon which member of the Hantavirus family is the culprit. Hantaan Virus and Dobrava Virus infections tend to attack more ferociously, while Seoul Virus, Saaremaa Virus and Puumala Virus are less severe.

Lines of Enquiry

Various lines of enquiry into how to prevent or limit the threat posed by Hantaviruses have been pursued by teams of scientists in several countries and over many years, but have not yet led to the development of a globally authorised safe and effective vaccine against any of the family’s prime suspects.

One such enquiry produced significant results for China and South Korea in the 1990s, however, when a vaccine against Haemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome was developed. The vaccine, which is bivalent and based on inactivated forms of Hantaan Virus and Seoul Virus, has been approved for use by China and South Korea.

For Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome, no vaccine has yet been successfully developed, although scientists are investigating the use of several different types of vaccine technology to target the Hantaviruses that cause HPS. Many of these candidate vaccines are showing promise in early-stage trials, but more work is needed to progress one or more of them through to full development and regulatory approval.

Editor's note:

The naming and classification of viruses into various families and sub-families is an ever-evolving and sometimes controversial field of science.

As scientific understanding deepens, viruses currently classified as members of one family may be switched or adopted into another family, or be put into a completely new family of their own.

CEPI’s series on The Viral Most Wanted seeks to reflect the most widespread scientific consensus on viral families and their members, and is cross-referenced with the latest reports by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).

Related articles

Related articles

The Hantaviruses

Some Hantaviruses focus their attacks on blood vessels in the lungs, causing the blood to leak out and ultimately ‘drowning’ their victims.

The Flaviviruses

Yellow Fever is now known as one of several deadly viral haemorrhagic fevers currently classified a Flavivirus, one of The Viral Most Wanted.

The Poxviruses

The viral family of one of the most fearsome contagious diseases in human history

The Retroviruses

The most nefarious Retrovirus—HIV—has infected 85 million and killed 40 million people worldwide.

Matonaviruses and Togaviruses

Multiple lines of enquiry against Chikungunya virus and its viral relatives are being pursued by scientists around the world, with the hope for a new protective vaccine coming very soon.

The Filoviruses

“one of the most lethal infections you can think of” - and it's one whose deadly reach is extending ever further

The Coronaviruses

Seven members of the Coronavirus family are already known to infect people, often with deadly consequences. Disease investigators fear that more new and dangerous Coronaviruses could spill over at any time.

The Nairoviruses

The prime suspect in this family is a deadly virus that causes its human victims to bleed profusely.

The Arenaviruses

The Arenavirus family includes some of the most lethal haemorrhagic fevers known. All its prime suspects can cause life-threatening disease and death

The Phenuiviruses

The most infamous Phenuivirus, Rift Valley fever, poses a significant threat to people and livestock causing serious disease and dangerous outbreaks.

The Picornaviruses

Large, persistent and deadly outbreaks of a crippling infection caused by one member of this viral family meant that it was once among the most feared diseases in the world

The Paramyxoviruses

This family contains one of the most contagious human viral diseases, as well as one of the most deadly. Explore The Paramyxoviruses.