The Filoviruses

Dr Jean-Jacques Muyembe was a newly-qualified microbiologist working as a field epidemiologist when he got a call in 1976 to help investigate an outbreak. A pernicious disease had taken hold in the village of Yambuku in central Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo. People were dying in large numbers of the infection – one that appeared at first to be like malaria or typhoid or yellow fever, but was clearly something even worse.

Muyembe knew that some of the Belgian nuns working in the village had been vaccinated against yellow fever and typhoid, yet this infection was easily flooring those defences. It was a swift and gruesome new killer.

Reflecting on his experience with these first few patients, Muyembe said the most striking thing was when he drew blood from them. Removing the syringe and needle, he found that the tiny puncture hole would continue to gush blood. It was the first time he’d seen such a thing, he recalled, and he knew it was an ominous sign.

After asking one of the infected nuns to fly back with him to Kinshasa, Muyembe took blood samples from her and sent them to Belgium for testing. The analysis that followed produced a shocking result. The blood of the nun, who by now had been killed by the disease, was infected with a virus that caused an acute haemorrhagic fever – one that scientists now describe as “one of the most lethal infections you can think of”.

The pathogen swiftly became known as Ebolavirus after the river that runs near Yambuku where it infected the villagers and the nuns. It was also swiftly recognised as a member of the Filovirus family - one of The Viral Most Wanted.

One Big Close-Knit Family?

Despite having multiple viral members, the Filovirus family is indeed a fairly close-knit unit. When it comes to family members that cause human disease and death, the Filoviruses have two important, genetically distinct but related subgroups - the Ebolaviruses and the Marburgviruses - which have many common traits.

Prime Suspects

The most menacing member of the Filovirus family is Ebola - or more specifically the Zaire Ebolavirus that caused a devastating two year-long epidemic in West Africa beginning in 2014. Besides Zaire Ebolavirus, the Ebolavirus subgroup of the Filoviruses includes three more prime suspects: Sudan Ebolavirus - a close cousin of Zaire, Taï Forest Ebolavirus and Bundibugyo Ebolavirus. Disease detectives are also wary of two other members of the Ebolavirus subgroup which have not yet been known to cause disease in people. These are Reston Ebolavirus and Bombali Ebolavirus.

Within the Marburgvirus subgroup of the Filoviruses, Marburg Virus and Ravn Virus are the key culprits.

Nicknames and Aliases

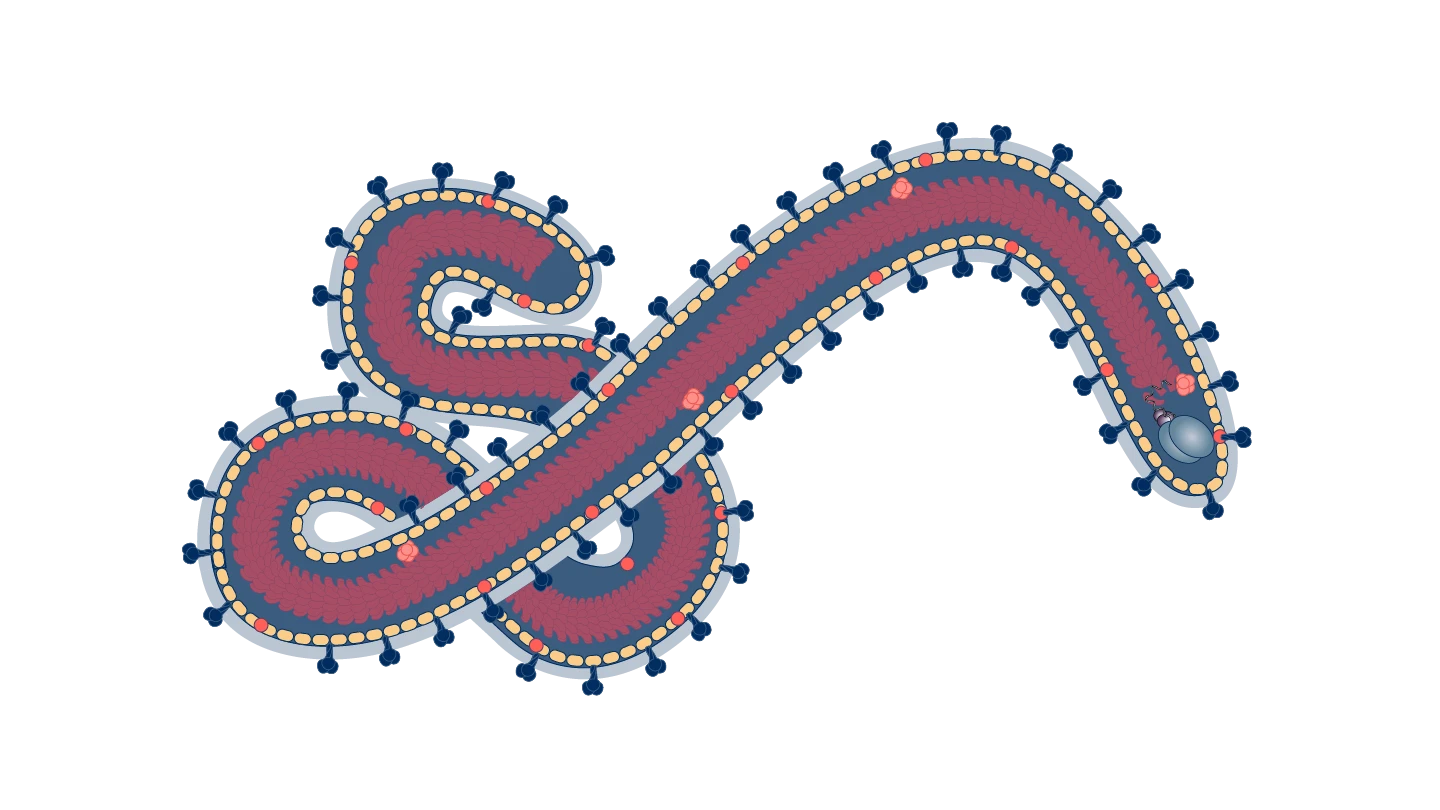

The name Filovirus is derived from the Latin word ‘filum’, meaning ‘thread’, and describing its thin, flexible, threadlike appearance.

Ebolaviruses take their name from the Ebola River in DRC - formerly Zaire - where the first one was identified in 1976.

Since then, each type of Ebolavirus has also adopted the name of the place where it was first identified: Taï Forest Ebolavirus, which was also known in the past as Côte d'Ivoire Ebolavirus, was found in a single fatal case of infection of a scientist working in the Tai Forest reserve, while Bombali Ebolavirus was found in the Bombali region in the north of Sierra Leone.

Bundibugyo Ebolavirus takes its name from the district of western Uganda where it first emerged in 2007 and Reston Ebolavirus is named after the town of Reston in the U.S. state of Virginia, where it was first found in macaque monkeys that had been imported from the Philippines.

Distinguishing Features

One unique aspect of Filoviruses is their distinctive shape. They are enveloped viruses with a single-stranded RNA genome. Filovirus virions, or virus particles, are long and ribbon- or thread-like and appear to snake into distinctive shapes under a microscope. Some investigators say the shape resembles a shepherd’s crook.

Modus Operandi

Filovirus particles use a protein known as a glycoprotein to bind to receptors on the surface of host cells. The binding of these receptors triggers what Filovirus specialists refer to as a cell “eating” process called macropinocytosis. This process, in turn, results in the Filovirus being engulfed by a wave-like motion of a host cell’s membrane and taken into the cell, where it replicates and begins to spread.

Accomplices

Fruit bats, apes and monkeys all act as accomplices to the spread of Filoviruses from animals to people, especially Ebolaviruses. Ebola outbreaks often start with a so-called index case - the first person to become infected - getting sick after eating bushmeat or having contact with the bodily fluids, droppings or flesh of a bat or primate carrying the virus.

To spread between people, Filoviruses tend to need no accomplices. Person-to-person transmission of Ebola, for example, is via contact with urine, saliva, sweat, faeces, blood, vomit, breast milk, or semen of a person who is sick with or has died from an Ebolavirus infection.

Common Victims

Filoviruses can infect people of any gender or age. Since all six known types of Ebolavirus, as well as the two known Marburg viruses, are known to spread through direct contact with an infected person or animal, people at highest risk are those who have direct interactions with wildlife or with human cases.

This means that people who eat bushmeat such as meat from bats, monkeys and apes are at higher risk of falling victim to members of the Filovirus family. And in Ebola outbreaks, healthcare workers who don’t have full personal protective equipment and close friends and family members of sick patients are particularly vulnerable to infection.

Because of its transmission route - which puts those caring for sick loved ones, washing the bodies of the dead, or attending their burials at high risk of becoming sick themselves – Ebola was sometimes described during the West Africa outbreak as “a disease of love”.

Infamous Outbreaks

By far the largest, longest, most complex and most deadly Filovirus outbreak in history was the 2014 to 2016 Zaire Ebolavirus epidemic in West Africa. Starting with around 50 cases reported among people living in forested areas of south-eastern Guinea, the outbreak swiftly spread to the neighbouring countries of Sierra Leone and Liberia. By July 2014, it had reached the capital cities of these three countries and a month later, disease experts at the World Health Organization declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. During the following two years, the Ebola epidemic spread to another seven countries - Nigeria, Mali, Senegal, Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States. By the time it ended in June 2016, it had infected more than 28,000 people and killed at least 11,300 of them.

The West Africa epidemic was the seventh outbreak of Zaire Ebolavirus since the virus was first discovered in 1976. By the time it was declared over, it had caused more cases and deaths than all previous Zaire Ebolavirus outbreaks combined.

Sudan Ebolavirus has staged several attacks in Uganda, including a large and severe one in 2000, when it caused an outbreak of at least 425 infections with a case fatality rate of more than 50 percent. The Sudan strain of Ebola caused its most recent Ugandan outbreak in 2022, when it spread to nine districts and caused at least 164 human infections and 77 deaths until it was contained and ended in January 2023

Marburg outbreaks have historically been less frequent than those caused by other Filoviruses, but they nevertheless pose a significant threat. One of the largest and most deadly outbreaks of Marburg viral haemorrhagic fever was in Angola in 2004 and 2005. The disease ultimately spread to infect several hundred people, and 90 percent of those who contracted the disease died.

Recently, disease detectives have noted that Marburg virus outbreaks appear to be becoming more frequent and more widespread, with a number of deadly incidents cropping up in new regions or countries for the first time.

In 2023 alone, two countries that had never before reported cases of Marburg suffered deadly outbreaks. The first was in Equatorial Guinea, where 17 people across several provinces were infected with Marburg, 12 of them fatally.

A month after the Equatorial Guinea outbreak, Marburg virus cases were reported for the first time ever in Tanzania, in the northwest region of Kagera. This outbreak was curbed relatively quickly, but still managed to infect nine people and kill six of them.

Then in 2024, Rwanda saw its first ever cases of Marburg with an outbreak that began in a mining tunnel near Kigali that is home to a large colony of fruit bats. This outbreak was contained in a matter of months, with only 66 cases and 15 deaths, after Rwandan authorities immediately deployed an emergency outbreak response plan involving door-to-door surveillance, testing and contact-tracing and a clinical trial of a candidate Marburg vaccine.

Common Harms

Filovirus infections can have gruesome and often deadly effects on people.

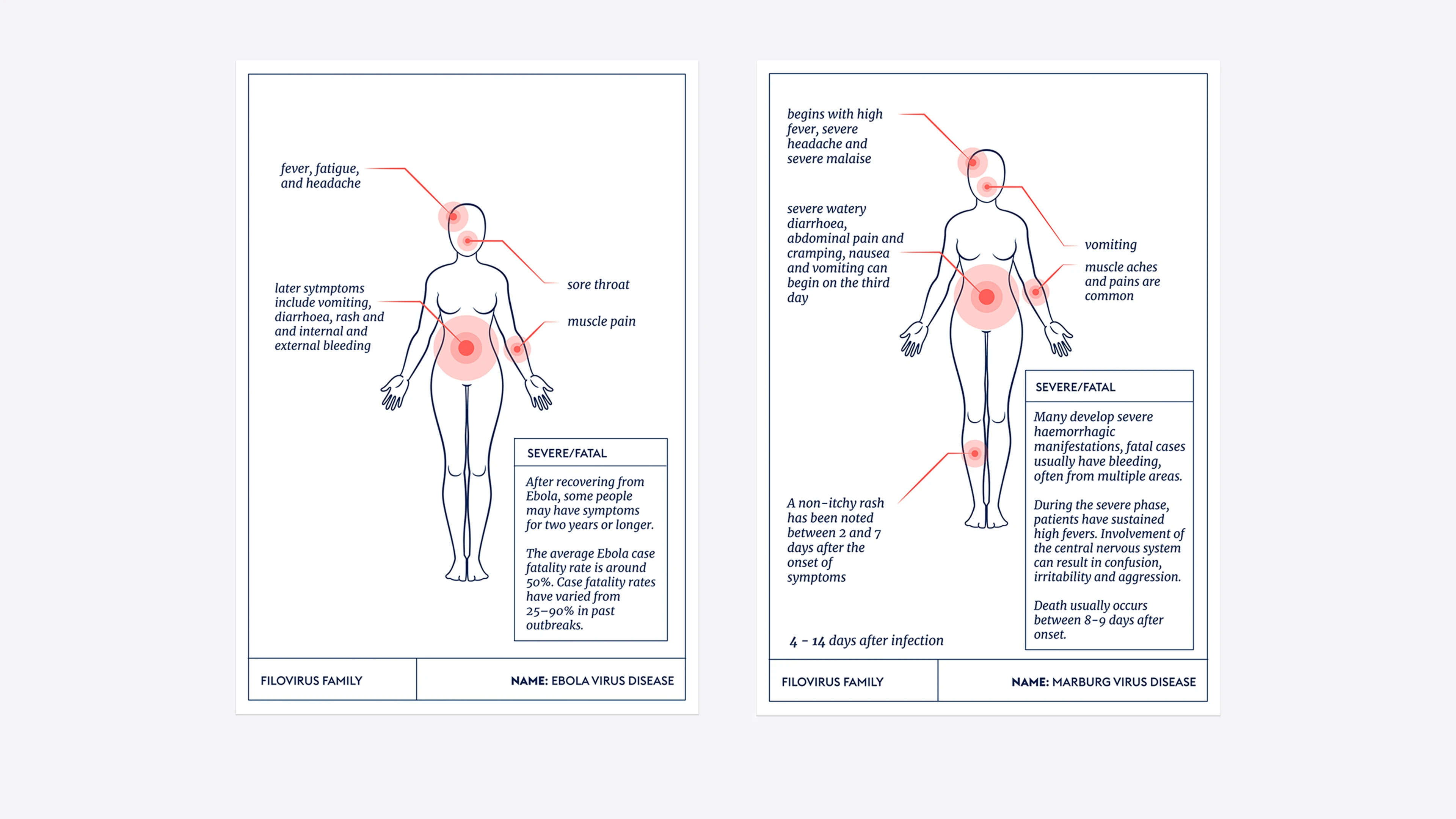

In victims of Marburg virus infection, the illness begins very suddenly with high fever, acute headache and severe malaise. Case notes detailing human outbreaks show that muscle aches, extreme watery diarrhoea, abdominal cramping, nausea and vomiting can begin by the third day. Patients are sometimes described as this stage as being “ghost-like”, with deep-set eyes, expressionless faces and extreme lethargy. Some Marburg victims have a rash during this mid-phase of illness, before going on to develop severe haemorrhagic systems within about a week of first falling sick. Internal and external bleeding is common and can be profuse, including from the nose, mouth and vagina. Those who are not able to overcome the viral attack are usually killed by it within nine days.

People infected with Zaire Ebolavirus or Sudan Ebolavirus suffer a largely similar series of symptoms. Because initial symptoms of fever, headache and muscle pain are similar to the early symptoms of other diseases like malaria and Yellow Fever, which are endemic to countries where Ebolavirus outbreaks often occur, the diagnosis of Ebolavirus infection is sometimes confused and delayed. Subsequent symptoms become increasingly severe, with vomiting, diarrhoea and, in many ultimately fatal cases, external and internal bleeding.

Lines of Enquiry

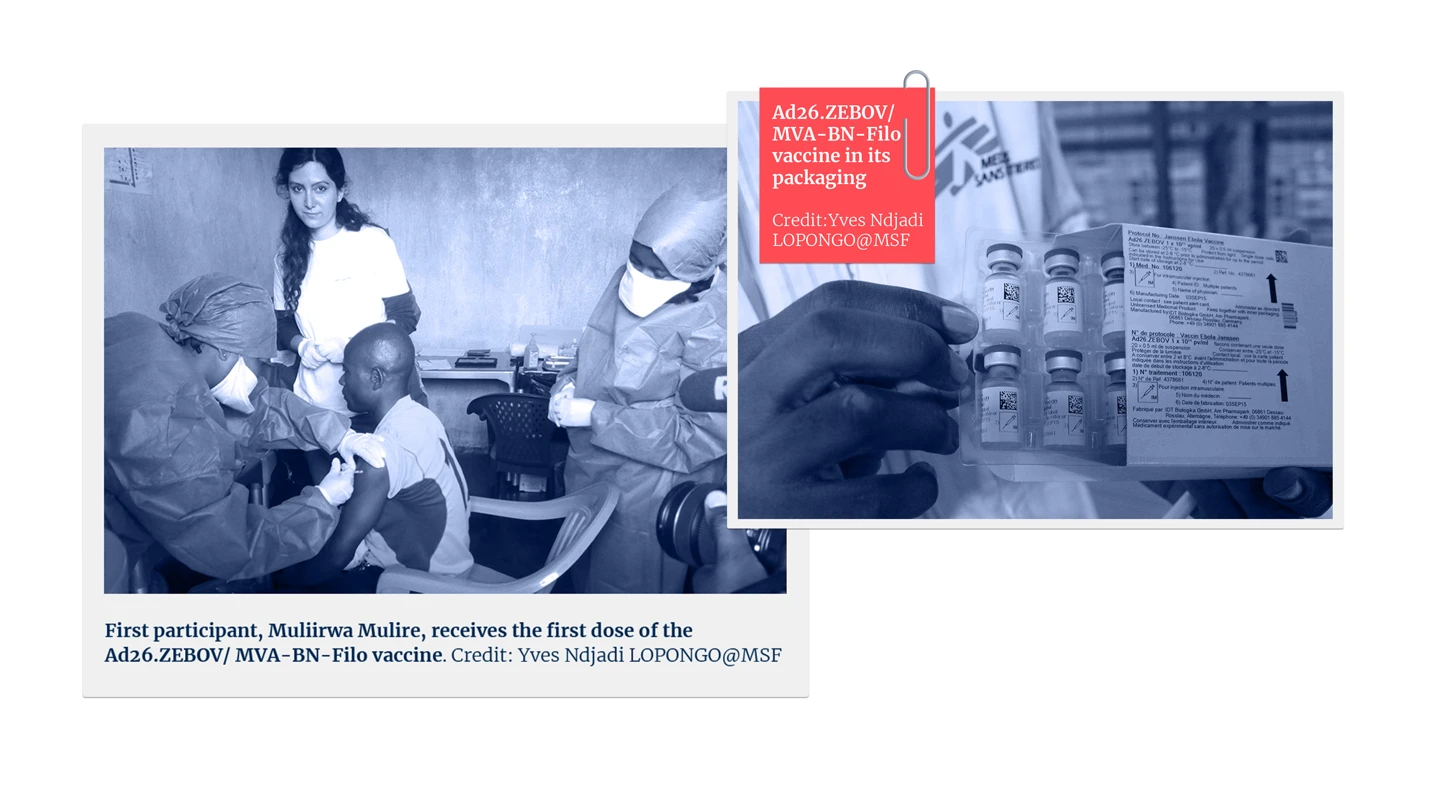

Although their work came tragically too late to make an impact on the biggest outbreak of Ebola in recorded history - the devastating West Africa epidemic in 2014 to 2016 - vaccinologists have now successfully developed two approved vaccines against Zaire Ebolavirus vaccines. Both the single-dose Ervebo vaccine and the two-shot Zabdeno plus Mvabea vaccines are licensed by drugs regulators and approved by the World Health Organization. These scientific successes mean that now, when new outbreaks of Zaire Ebolavirus crop up, disease detectives are able to swiftly deploy defensive immunisation strategies to contain their spread and minimise the number of victims.

During an outbreak of Zaire Ebolavirus in The Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2019 – the second largest outbreak of this disease in history - CEPI joined a consortium to support the DRC government in conducting a large-scale clinical trial of the two-shot vaccine. CEPI is also supporting ongoing research to help expand access to Zaire Ebolavirus vaccines to vulnerable groups and at-risk populations, including pregnant women.

Scientific investigations into how to protect people against other deadly Filoviruses are active and also showing some promise. Several potential vaccines against Sudan Ebolavirus are in development. Towards the end of an outbreak of Sudan Ebola in Uganda in 2022 doses of the first candidate vaccine arrived in the country in record time – just 79 days after the Uganda outbreak began – but the planned trial was no longer needed because the outbreak was already petering out, with fewer and fewer cases.

As another line of enquiry on Ebolaviruses, CEPI is supporting the development of an international antibody standard against Sudan Ebolavirus. When it is successfully established, the antibody standard will become an important scientific tool for assessing and comparing the performance of experimental vaccines against the deadly disease.

Editor's note:

The naming and classification of viruses into various families and sub-families is an ever-evolving and sometimes controversial field of science.

As scientific understanding deepens, viruses currently classified as members of one family may be switched or adopted into another family, or be put into a completely new family of their own.

CEPI’s series on The Viral Most Wanted seeks to reflect the most widespread scientific consensus on viral families and their members, and is cross-referenced with the latest reports by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).

Related articles

Related articles

The Arenaviruses

The Arenavirus family includes some of the most lethal haemorrhagic fevers known. All its prime suspects can cause life-threatening disease and death

The Nairoviruses

The prime suspect in this family is a deadly virus that causes its human victims to bleed profusely.

The Coronaviruses

Seven members of the Coronavirus family are already known to infect people, often with deadly consequences. Disease investigators fear that more new and dangerous Coronaviruses could spill over at any time.

The Paramyxoviruses

This family contains one of the most contagious human viral diseases, as well as one of the most deadly. Explore The Paramyxoviruses.

Matonaviruses and Togaviruses

Multiple lines of enquiry against Chikungunya virus and its viral relatives are being pursued by scientists around the world, with the hope for a new protective vaccine coming very soon.

The Flaviviruses

Yellow Fever is now known as one of several deadly viral haemorrhagic fevers currently classified a Flavivirus, one of The Viral Most Wanted.

The Hantaviruses

Some Hantaviruses focus their attacks on blood vessels in the lungs, causing the blood to leak out and ultimately ‘drowning’ their victims.

The Retroviruses

The most nefarious Retrovirus—HIV—has infected 85 million and killed 40 million people worldwide.

The Orthomyxoviruses

These viral culprits have caused the deadliest pandemics in human history

The Phenuiviruses

The most infamous Phenuivirus, Rift Valley fever, poses a significant threat to people and livestock causing serious disease and dangerous outbreaks.

The Picornaviruses

Large, persistent and deadly outbreaks of a crippling infection caused by one member of this viral family meant that it was once among the most feared diseases in the world

The Poxviruses

The viral family of one of the most fearsome contagious diseases in human history