Preparedness in practice: Rwanda’s record-breaking Marburg response

CEPI’s Outbreak Response function is aimed at enabling rapid and cohesive responses to outbreaks that seek to protect people as well as deepen scientific knowledge to further research and development of vaccines and other medical countermeasures.

We spoke to CEPI’s outbreak response experts about how and why they want 100 Days Mission preparedness to become common practice.

___________

On September 11, 2024, at the Rwanda Biomedical Centre in Kigali, leading national health officials got together with local and international scientists for a special 100 Days Mission tabletop exercise. It used a fictional scenario to role play how to contain a future deadly disease epidemic within three months to neutralise its pandemic potential.

The first-of-its-kind exercise brought together more than 40 experts from seven organisations from all over the world and, in a day of intense discussion, helped them forge new partnerships, identify risks, strengths and gaps in outbreak response planning, as well as deepen their understanding of both each other and of disease epidemics.

“We’re going to get into some very complex issues here,” CEPI’s CEO Dr Richard Hatchett cautioned as he opened the meeting. “(And) the only way to be ready to address those in a crisis is to begin to chip away at them.”

The fictional future scenario they worked with, set in 2028, began like this:

A 23-year-old male worker from the main city abattoir is admitted to a Kigali healthcare facility with severe haemorrhagic symptoms. Within five days, healthcare workers who have had direct contact with the patient begin presenting with sudden-onset, flu-like symptoms: fever, muscle pain, joint pain and headaches. Three of these healthcare patients develop severe haemorrhagic symptoms, and one dies.

What the group of international experts didn’t know as they considered this fictional outbreak, was that at almost exactly the same time—early September 2024—in Tunnel 12 of Rwanda’s Gamico tin mine, a 27-year-old miner had unwittingly picked up an actual viral disease.

The pathogen from Tunnel 12—later identified as the highly deadly Marburg Virus — made its way into the miner’s body and began replicating there, causing fever, body aches and general malaise. Not knowing what was making him ill, the man unwittingly passed the virus on to his pregnant wife. And a few days later, the increasingly sick couple were admitted to the University Teaching Hospital in Kigali, where they in turn went on to infect several healthcare workers with the haemorrhagic virus.

By September 26, it was clear to Minister for Health Dr Sabin Nsanzimana that Rwanda had a very real and deadly Marburg outbreak on its hands.

Marburg is a known disease but it had never been seen in Rwanda before and there are no licensed vaccines or treatments against it. Yet—thanks in part to the fresh learnings from the tabletop exercise a few weeks earlier—Minister Sabin and colleagues at the Rwanda Biomedical Centre knew almost immediately that they had the knowledge and capability both to contain the outbreak as swiftly as possible and at the same time help scientists make progress on the development of potential vaccines against Marburg.

Using lessons and connections from the eerily prescient tabletop exercise they had role-played, they put in late-night calls to CEPI CEO Richard Hatchett, the Sabin Vaccine Institute in the U.S. and other global health contacts. Simultaneously, they initiated an immediate and intensive door-to-door surveillance, testing and contact-tracing operation.

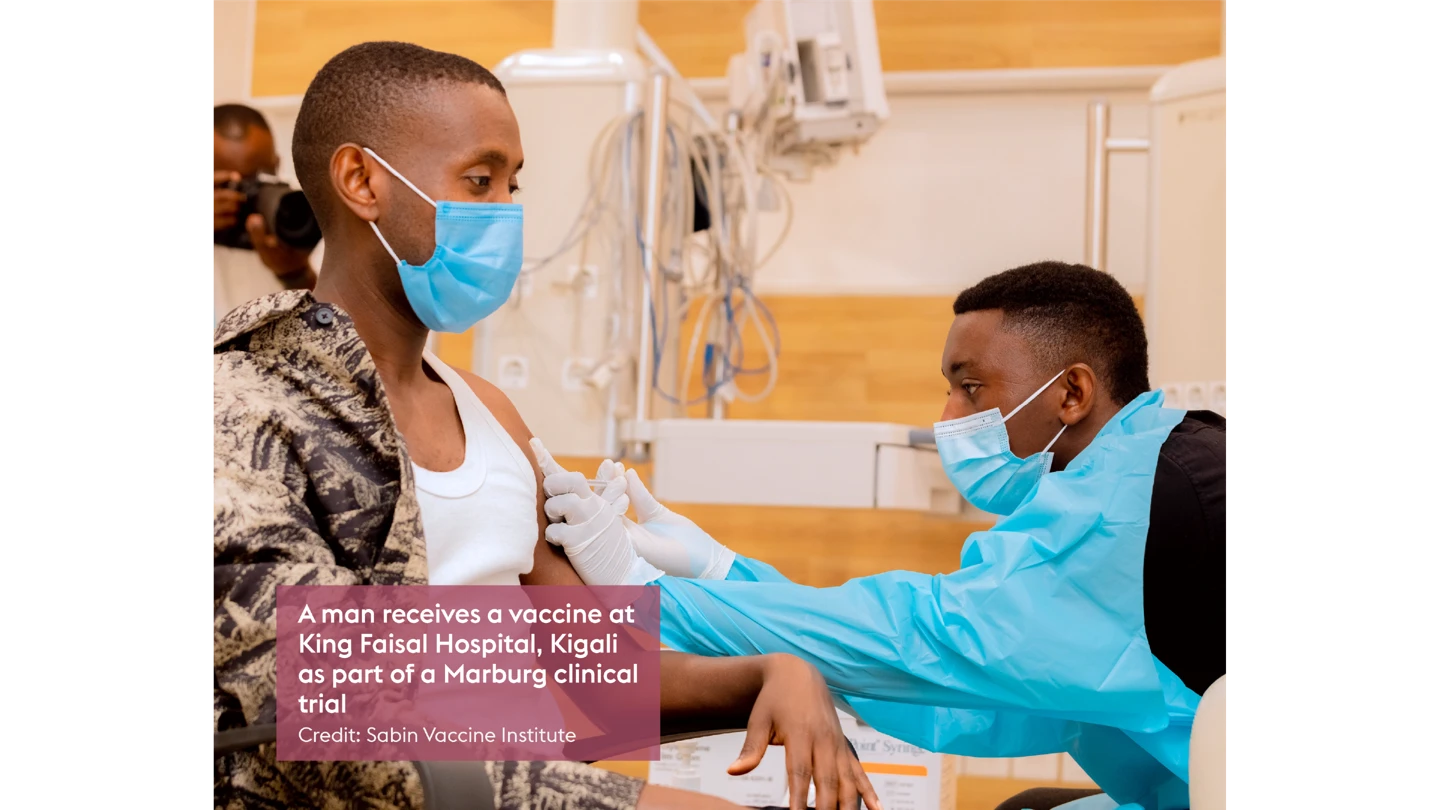

Working with CEPI and the Sabin Vaccine Institute—a non-profit which has been developing a Marburg vaccine and had experimental doses ready for use in clinical trials—Rwanda was able to implement an emergency trial of the vaccine just 10 days after the outbreak was declared.

“This amazing response was one of the best examples yet of how preparedness, practice and trust can pay huge, life-saving dividends when it comes to tackling real-life deadly disease outbreaks,” said Dr Nicole Lurie, CEPI’s Executive Director of Preparedness and Response.

“Not only was it an immensely positive experience of partnership and teamwork, but it also served as a vital reminder that rapid and effective outbreak response is very possible when multiple partners know what to do and can do it together.”

CEPI’s outbreak response experts are keen to replicate and build on this success by working with other governments around the world to conduct 100 Days Mission exercises that help national authorities test their response strategies, identify and close gaps and forge partnerships that will improve coordination at times of crisis or threat.

Essentially, such simulated outbreak scenarios serve as a way to help national policymakers and partners in both the public and private sector, together with CEPI and other international organisations, practice and train so that they are ready to act swiftly when a real disease outbreak erupts.

The plan is to extend the exercises from tabletop to functional and then so-called live-fire practice sessions—exercises that involve the real mobilisation of resources, rather than theoretical or simulated actions—so that countries learn how to work across sectors to prepare in advance as many as possible of the capabilities needed for swift and effective outbreak response, and learn how to take “no regrets” decisions early in an emerging epidemic.

Rwanda’s Minister Sabin is in no doubt that practicing such preparedness is a life-saver.

On December 20, 2024—the day the historic Marburg outbreak in Rwanda was brought to an end in record time—he wrote in Britain’s Telegraph newspaper: “The partnerships and preparedness that helped bring this Marburg outbreak to such a swift end saved many lives in Rwanda and helped protect the rest of the world from a potentially catastrophic deadly epidemic.”