The Nairovirus Family

For a few terrible days in October 2008, healthworkers at a hospital in the Sudanese town of Al-Fulah could do little more than watch, helpless, as a 60-year-old man in their care began bleeding from almost every part of his body. The patient, who had been working as a butcher, had come to the Kordufan region rural hospital suffering with a high fever, acute chills and constant headache. Now he was bleeding from the nose, his vomit was black and streaked with blood, and he had severe and bloody diarrhoea. Five days after his first symptoms appeared, he was dead.

Doctors conducting a follow-up investigation suspected the source of the man’s disease was most probably contaminated tissue and blood from an animal he’d butchered, but they could not conclude this for certain. What they did establish, however, was that the man’s agonising death was a result of Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever (CCHF)—a tick-borne viral disease first identified more than 2,000 miles away and more than half a century earlier in the Crimean Peninsula.

This 2008 Sudan outbreak—in which person-to-person spread led to several doctors, nurses and members of the butcher’s family also being infected and killed—was just one of multiple small but deadly outbreaks of CCHF that have erupted in many parts of the world since the disease first emerged in 1944. The virus that causes it is a member of the Nairovirus family, one of The Viral Most Wanted.

One Big Close-Knit Family?

The Nairovirus family is not particularly large but it does have more than 40 members, most of which are viruses that infect wild and domestic animals rather than people. The family has three subgroups, but two of these, the Shaspiviruses and the Striwaviruses, have only one known member each. The third subgroup, the Orthonairoviruses, is by far the largest of the three and contains scores of closely related viruses.

Prime Suspects

The number one suspect within the Nairovirus family is CCHF Virus. It is the only well-established member of this viral family known to cause widespread and frequent outbreaks of severe and deadly disease in humans. Other menaces within the Nairovirus family include Nairobi Sheep Disease Virus, Dugbe Virus and Hazara Virus. These viruses infect cattle, sheep, goats and other livestock. Very rarely they also cause disease in people.

Nicknames and Aliases

When CCHF disease was first identified in the Crimean Peninsula 1944, it was given the name of the place where it was found. But around a quarter of a century later, disease detectives discovered that another haemorrhagic fever-causing pathogen that had been infecting and killing people in the Congo Basin since 1956 was exactly the same virus. In 1969, the disease was renamed Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever to reflect its dual roots. Nairobi Sheep Disease Virus earned its name from the city in Kenya where it originated and from the animals who are its most common victims. In the Indian subcontinent, Nairobi Sheep Disease Virus goes by the alias Ganjam Virus. The tick-borne Dugbe Virus and Hazara Virus, both of which infect animals but rarely people, take their names from the places where they were first identified, respectively in Nigeria in 1964, and in India in 1954.

Distinguishing Features

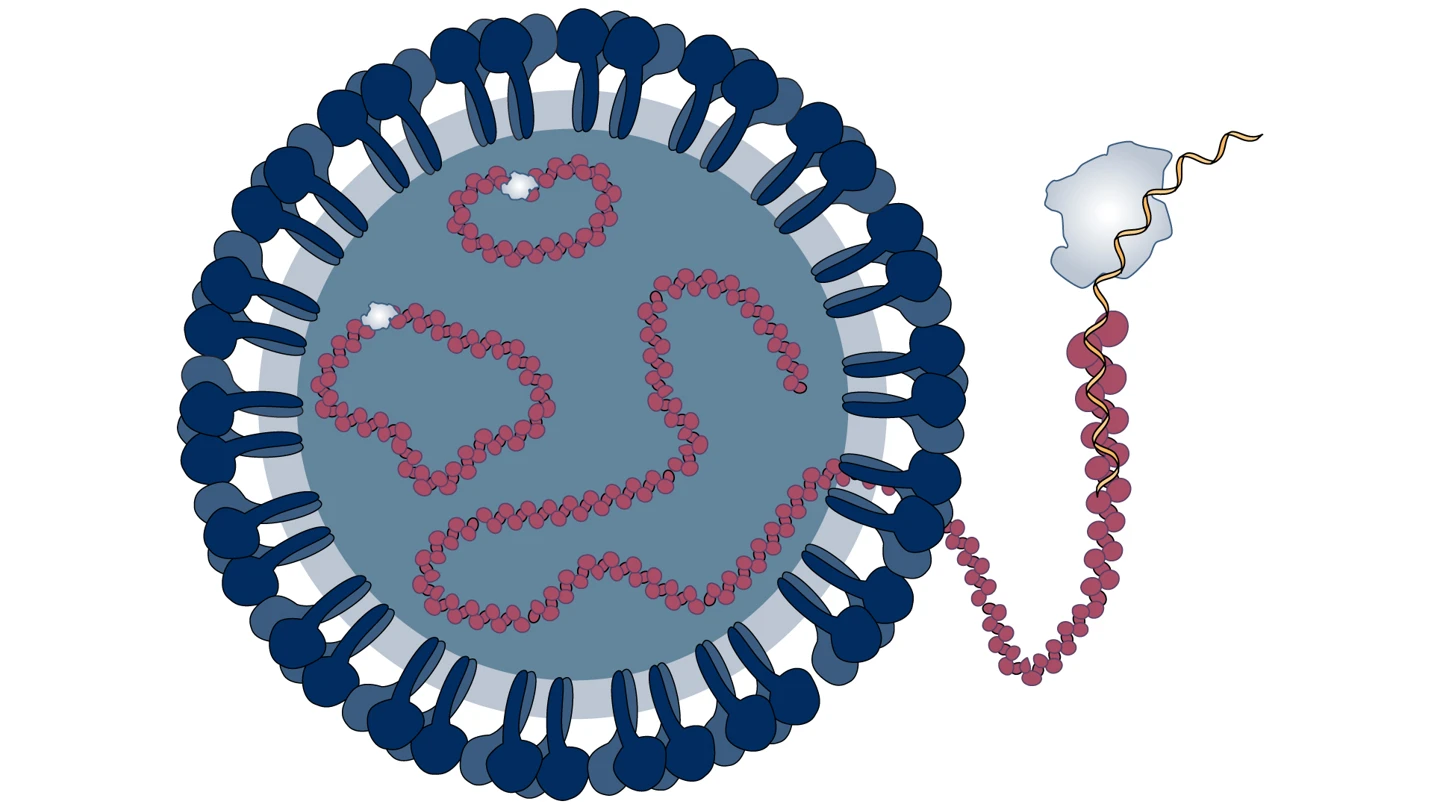

The viral particles, or virions, of the Nairovirus that causes CCHF are spherical with a diameter of 80 to 100 nanometers. They are enveloped, or cloaked, in a membrane that is studded with multiple minuscule protrusions made up of different types of proteins.

Modus Operandi

The CCHF virus infects its human victims by entering through cells called epithelial cells. These are found on the skin, in blood vessels and in various organs. The virus replicates and then spreads by entering the lymphatic system and infecting major organs such as the liver and spleen — ultimately causing multi-organ failure.

Accomplices

Nairoviruses are primarily carried and spread by ticks, specifically hard-shelled or ixodid ticks, which explains why they mostly infect wild and domestic animals.

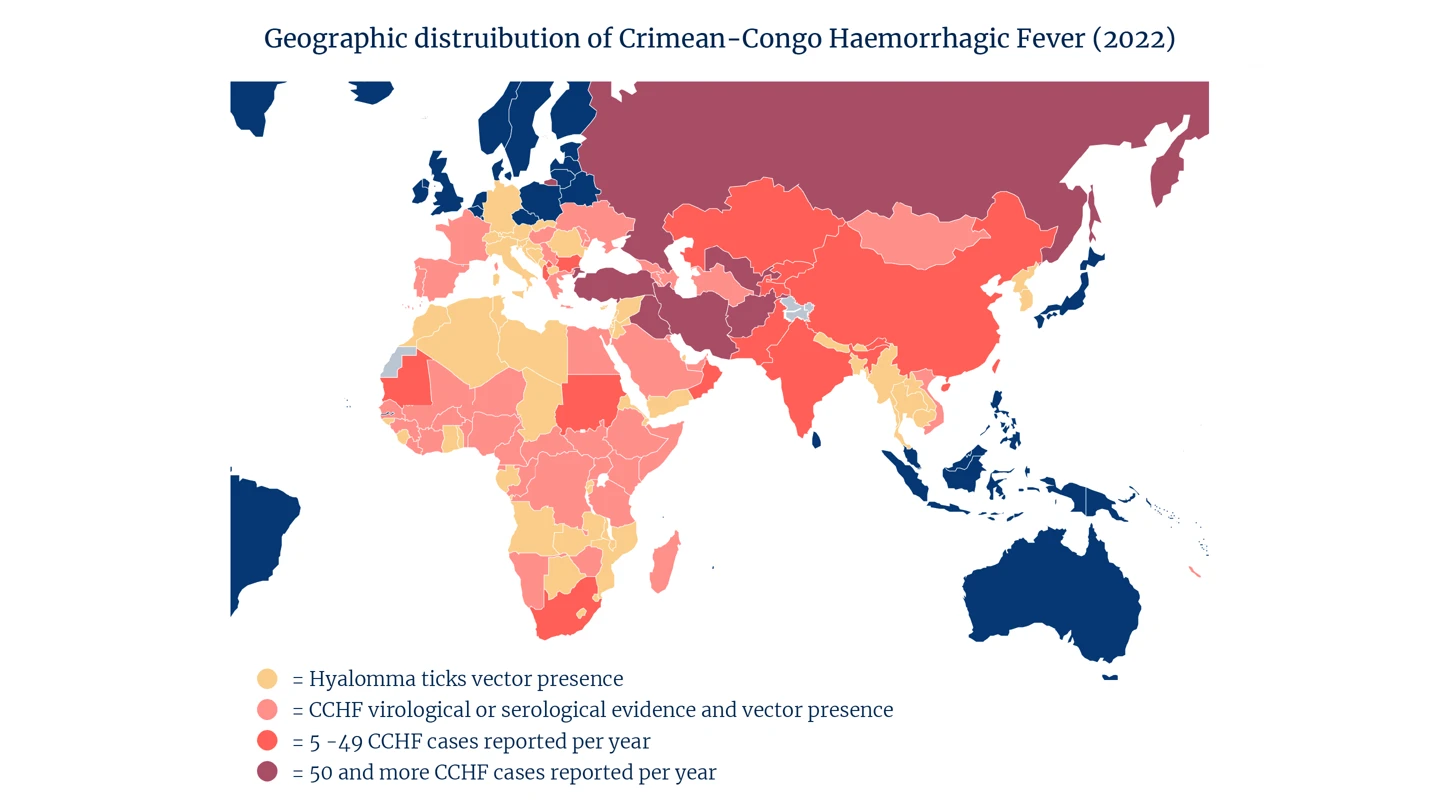

The chief accomplice for the deadly CCHF Virus is a tick known as Hyalomma marginatum. These Hyalomma ticks are widespread across Africa and Asia, and also found in many parts of southern and eastern Europe.

Many types of wild and domestic animals that Hyalomma ticks feed on become intermediate hosts and secondary accomplices of the CCHF Virus. These include livestock, horses, dogs, chickens, camels, ostriches, pigs, hares, deer, buffalo and even rhinoceroses. Outbreak investigators believe these animal hosts—who do not get sick with CCHF but remain asymptomatic—are largely responsible for the very wide geographical distribution of the virus because the ticks are transported with them during trading or migration.

CCHF can also be spread from person to person via close contact with the blood, organs or bodily fluids of someone infected with the virus.

Common Victims

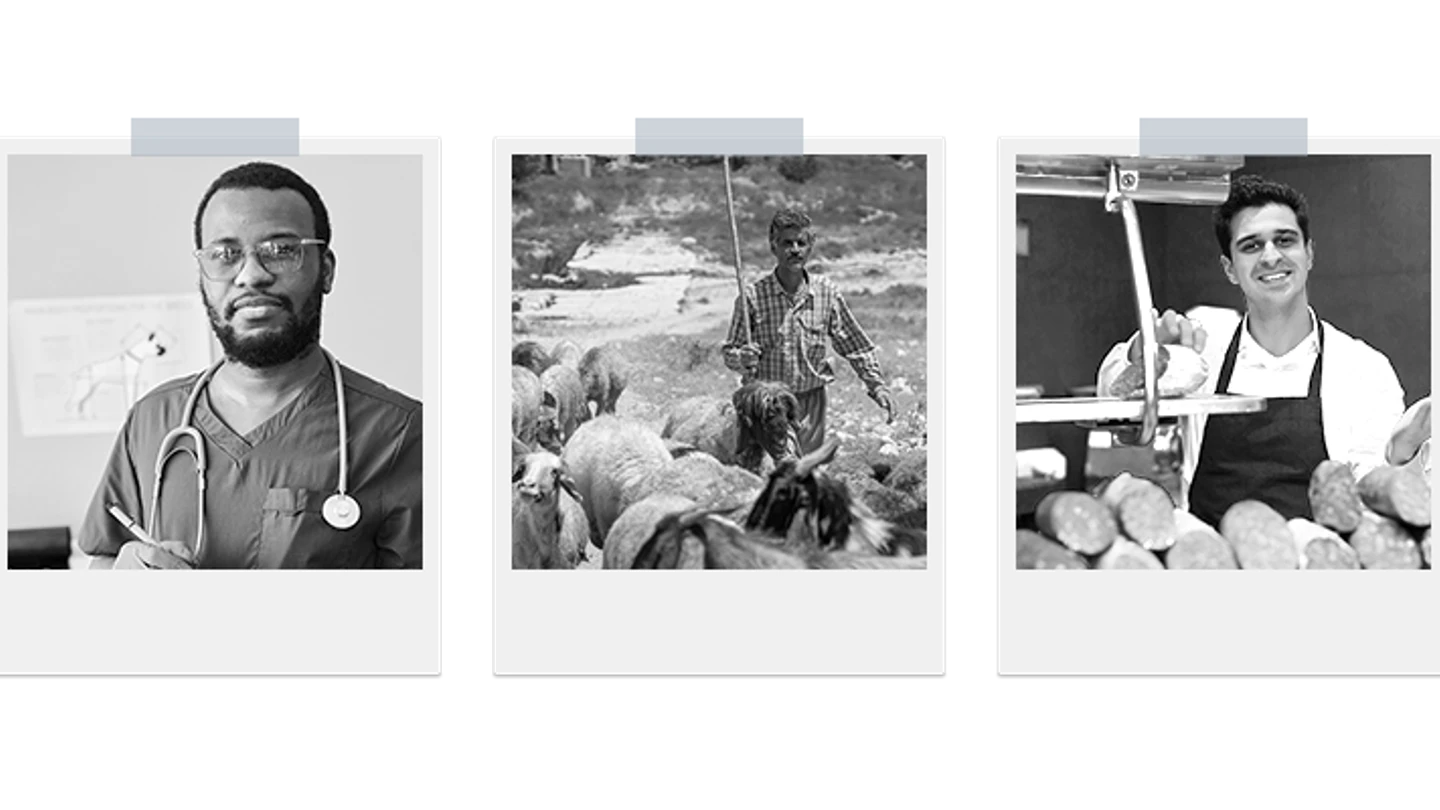

CCHF is endemic in all of Africa, the Balkans, the Middle East and in Asia. Because it is spread via ticks and via contact with infected animals, the disease’s most common victims are livestock workers, vets, slaughterhouse workers and butchers.

Other people who spend a lot of time in wildlife and who may be bitten by virus-carrying ticks, such as soldiers, farmers, forest workers and hikers, are also at higher risk of contracting CCHF.

Disease detectives analysing surges in cases of CCHF infection during important religious festivals like the Islamic Eid-ul-Adha Feast of Sacrifice suspect these may be sparked by the transportation of infected livestock from rural to urban areas for slaughter.

Infamous Outbreaks

The viral particles, or virions, of the Nairovirus that causes CCHF are spherical with a diameter of 80 to 100 nanometers. They are enveloped, or cloaked, in a membrane that is studded with multiple minuscule protrusions made up of different types of proteins.

CCHF

The first known outbreak of CCHF was in Crimea at the end of World War Two when about 200 Soviet military personnel were infected.

Disease detectives say that Turkey, specifically the mid-eastern Anatolian region of the country, appears to have a particular problem with recurring outbreaks of CCHF, which seem to come in seasonal waves. Case records from the Turkish Ministry of Health show that between 2002 and 2007, for example, at least 1,820 people in Turkey were infected with the viral disease, and around five percent of them died.

CCHF is now endemic in Turkey, as well as in at least 29 other countries around the world.

Investigators also became very concerned by several more recent notable outbreaks of CCHF: a persistent one in Kosovo, where the disease is now endemic, in which 228 people were infected, a quarter of them fatally, over a period of 18 years between 1995 to 2013; and another in Iraq in 2022 in which at least 212 people were infected and, of those, at least 27 died.

In August 2016, Spain recorded the first ever locally acquired case of CCHF in 62-year-old man who had been bitten by a Nairovirus-carrying tick.

Epidemiological experts now estimate that as many as three billion people globally live in areas where they are at risk of becoming infected with CCHF.

Common Harms

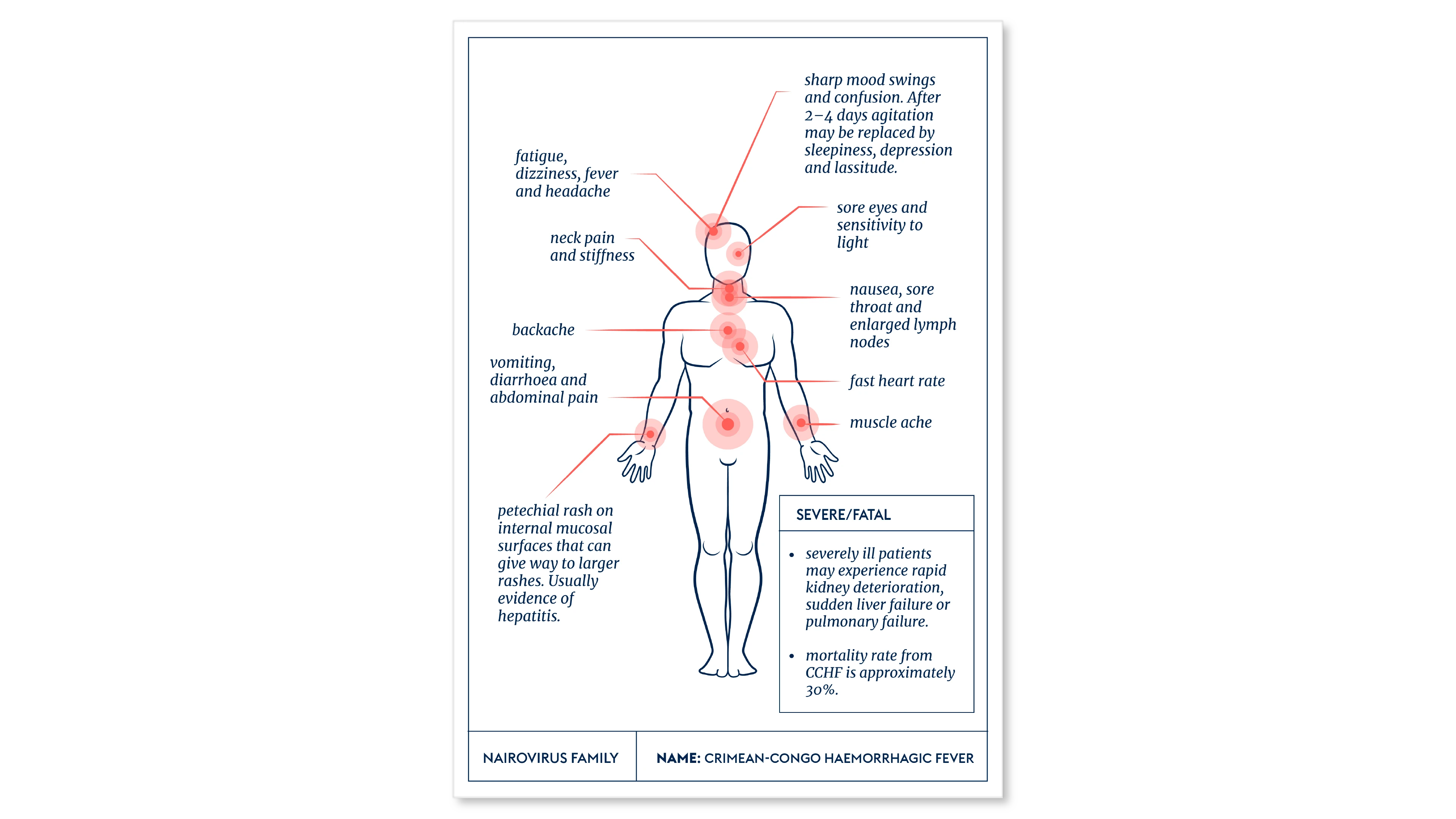

Victims of CCHF infection generally suffer a sudden and acute onset of initial symptoms, including a high fever, muscle aches, dizziness, neck pain, backache, headache, sore eyes and sensitivity to light. More severe symptoms of nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea follow, coupled with neurological confusion and mood swings.

The virus often causes hepatitis in more serious cases, and the most severely affected victims can suffer rapid kidney deterioration and sudden liver failure or pulmonary failure as early as the fifth day after falling sick.

Case fatality rates appear to vary widely in different outbreaks and different locations around the world. But death rates from CCHF can be as high as 40 percent.

Lines of Enquiry

Pursuing multiple lines of enquiry, disease detectives around the world are making encouraging progress in developing potential vaccines to defend against the Nairovirus family’s prime suspect.

Several types of CCHF vaccine are being explored, including development of candidates based on technologies that use mRNA, DNA, virus-like particles, or inactivated forms of the virus, and others that take a viral-vector-based approach.

One team of scientists in Britain is working on a CCHF vaccine that would use the same viral-vector platform as has been successfully used to make effective vaccines against SARS-CoV-2, a deadly virus in the Coronavirus Family.

While there is a CCHF vaccine deployed in Bulgaria, where it has been given to soldiers, other military personnel and some medics since the mid-1970s, there is limited publicly available evidence to show whether or not the shot is truly effective in reducing cases of infection with the CCHF Virus, or in reducing the severity of disease in those who do contract it.

Editor's note:

The naming and classification of viruses into various families and sub-families is an ever-evolving and sometimes controversial field of science.

As scientific understanding deepens, viruses currently classified as members of one family may be switched or adopted into another family, or be put into a completely new family of their own.

CEPI’s series on The Viral Most Wanted seeks to reflect the most widespread scientific consensus on viral families and their members, and is cross-referenced with the latest reports by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).

Related articles

Related articles

The Arenaviruses

The Arenavirus family includes some of the most lethal haemorrhagic fevers known. All its prime suspects can cause life-threatening disease and death

The Coronaviruses

Seven members of the Coronavirus family are already known to infect people, often with deadly consequences. Disease investigators fear that more new and dangerous Coronaviruses could spill over at any time.

The Paramyxoviruses

This family contains one of the most contagious human viral diseases, as well as one of the most deadly. Explore The Paramyxoviruses.

Matonaviruses and Togaviruses

Multiple lines of enquiry against Chikungunya virus and its viral relatives are being pursued by scientists around the world, with the hope for a new protective vaccine coming very soon.

The Flaviviruses

Yellow Fever is now known as one of several deadly viral haemorrhagic fevers currently classified a Flavivirus, one of The Viral Most Wanted.

The Hantaviruses

Some Hantaviruses focus their attacks on blood vessels in the lungs, causing the blood to leak out and ultimately ‘drowning’ their victims.

The Orthomyxoviruses

These viral culprits have caused the deadliest pandemics in human history

The Nairoviruses

The prime suspect in this family is a deadly virus that causes its human victims to bleed profusely.

The Retroviruses

The most nefarious Retrovirus—HIV—has infected 85 million and killed 40 million people worldwide.

The Phenuiviruses

The most infamous Phenuivirus, Rift Valley fever, poses a significant threat to people and livestock causing serious disease and dangerous outbreaks.

The Poxviruses

The viral family of one of the most fearsome contagious diseases in human history

The Filoviruses

“one of the most lethal infections you can think of” - and it's one whose deadly reach is extending ever further