The Parvoviruses and Hepeviruses

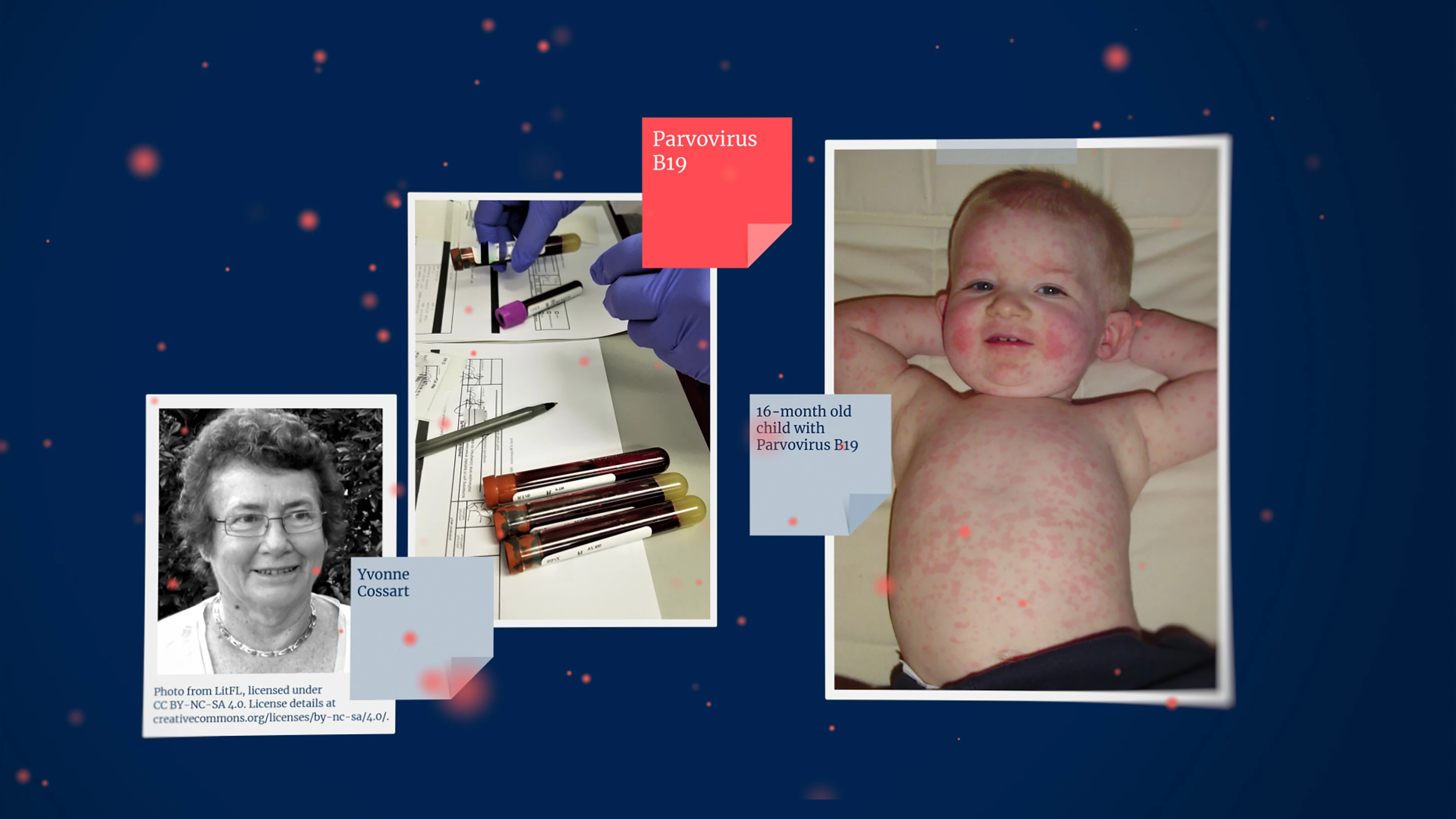

In 1974, an Australian virologist called Yvonne Cossart was screening blood samples for Hepatitis B virus when she accidentally came across a new viral attacker. This novel virus was not the one she’d been screening for at all, but one that looked very similar in shape and size to a group of pathogens called Parvoviruses that were known to infect animals. Identifying this new virus as a member of the same family, Cossart and her team named it according to the position and labelling of where they had found it: sample number 19, row B—and called it Parvovirus B19.

Less than a decade later, in 1983, the main culprit in the Hepevirus family was discovered by scientists investigating an outbreak of unexplained liver disease among Soviet soldiers during their occupation of Afghanistan. This virus—Hepatitis E—is now estimated to be the cause of 20 million infections worldwide each year, among which an estimated 3.3 million cases have symptomatic disease that includes liver inflammation and jaundice.

While neither of these viruses is currently believed to be a serious or imminent pandemic threat, each poses a significant disease and even death risk for vulnerable populations— particularly pregnant women. It is this risk that puts them among The Viral Most Wanted

Big Close-Knit Families?

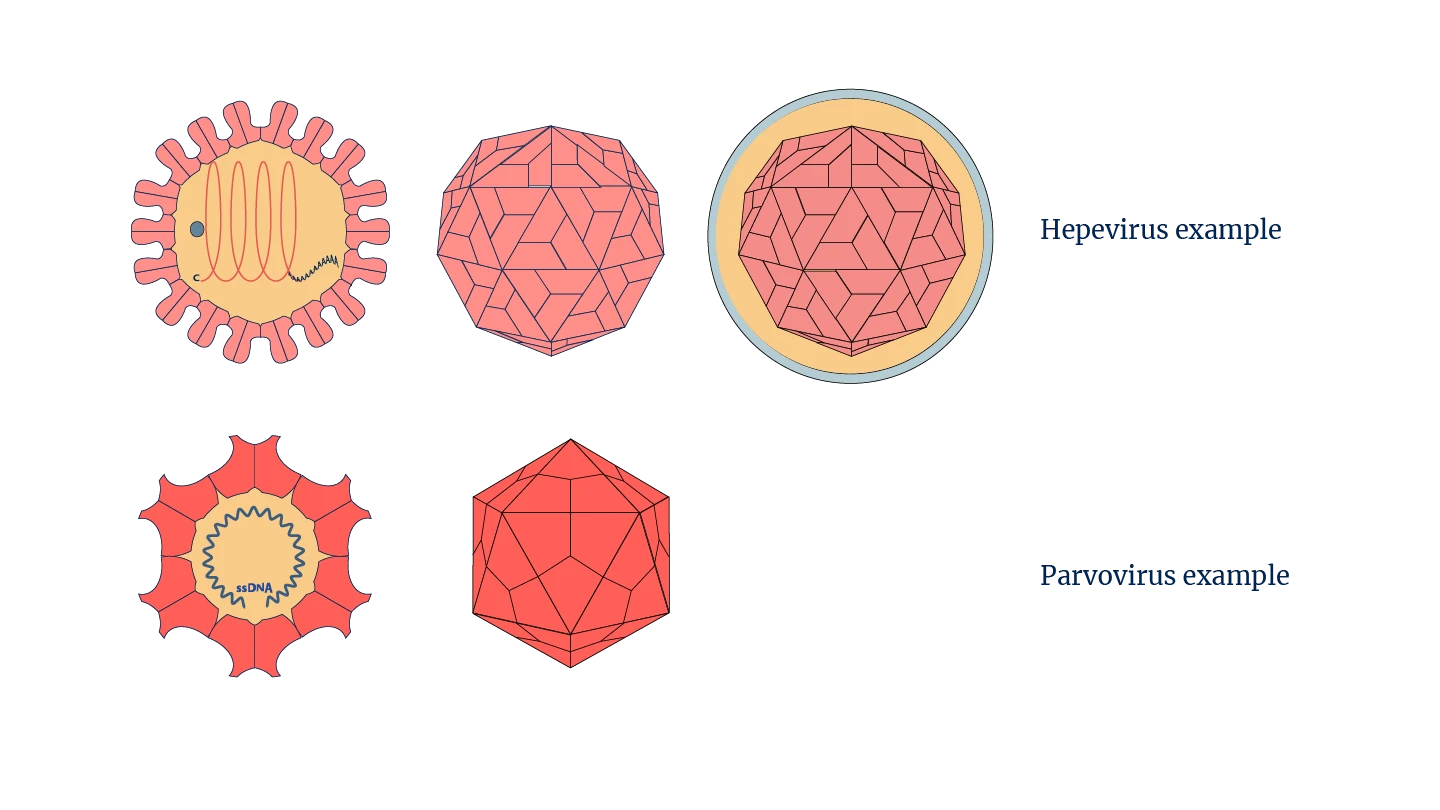

The Parvovirus and Hepevirus Families are quite distinct from each other and not closely related in terms of genetics and structure. Parvoviruses are small, non-enveloped DNA viruses, while Hepeviruses are also non-enveloped but tend to be slightly larger and have a single-stranded RNA genome.

Prime Suspects

Parvovirus B19 is the prime suspect within the Parvovirus family, closely followed by Human Bocavirus. Within the Hepevirus family, the main culprit in terms of human disease is Hepatitis E Virus.

Nicknames and Aliases

Parvovirus B19 goes under a variety of nicknames and aliases, including B19 Virus, B19V, Erythema Infectiosum and Fifth Disease. Because it causes a red rash on the faces of babies and young children who are infected, it is also often known as Slapped Cheek Syndrome, Slap Cheek or Slapped Cheek Disease. In Japan it is sometimes referred to as Nakatani Virus. The name Fifth Disease comes from it being the fifth in a list of historical classifications of common skin rash illnesses in children.

Hepatitis E Virus is sometimes shortened to Hep E.

Distinguishing Features

Parvovirus virions, or virus particles, are minuscule—measuring between 23 to 28 nanometres in diameter—and their DNA genome is encased in a 20-sided, or icosahedral, protein shell. They are exceptionally stable and robust, allowing them to remain infectious in the environment for months or even years.

Hepevirus virions are spherical particles measuring about 27 to 34 nanometres in diameter. Under an electron microscope, various spikes and bumps can be seen on their surfaces.

Source: Viral Zone by SwissBioPics

Modus Operandi

Parvovirus B19 targets specific cells known as erythroid progenitor cells, which are found in the bone marrow. The virus binds to a receptor on the cell surface called the P antigen. Once attached, the virus is taken into the cell where its DNA travels to the nucleus and hijacks the cell's machinery to replicate.

Hepeviruses use their surface proteins to attach themselves to specific receptors on the surface of human cells—primarily liver cells, which are also known as hepatocytes. The virus is then taken in and engulfed by the cell’s membrane. Inside, the viral RNA uses the host cell's machinery to produce new virus particles.

Accomplices

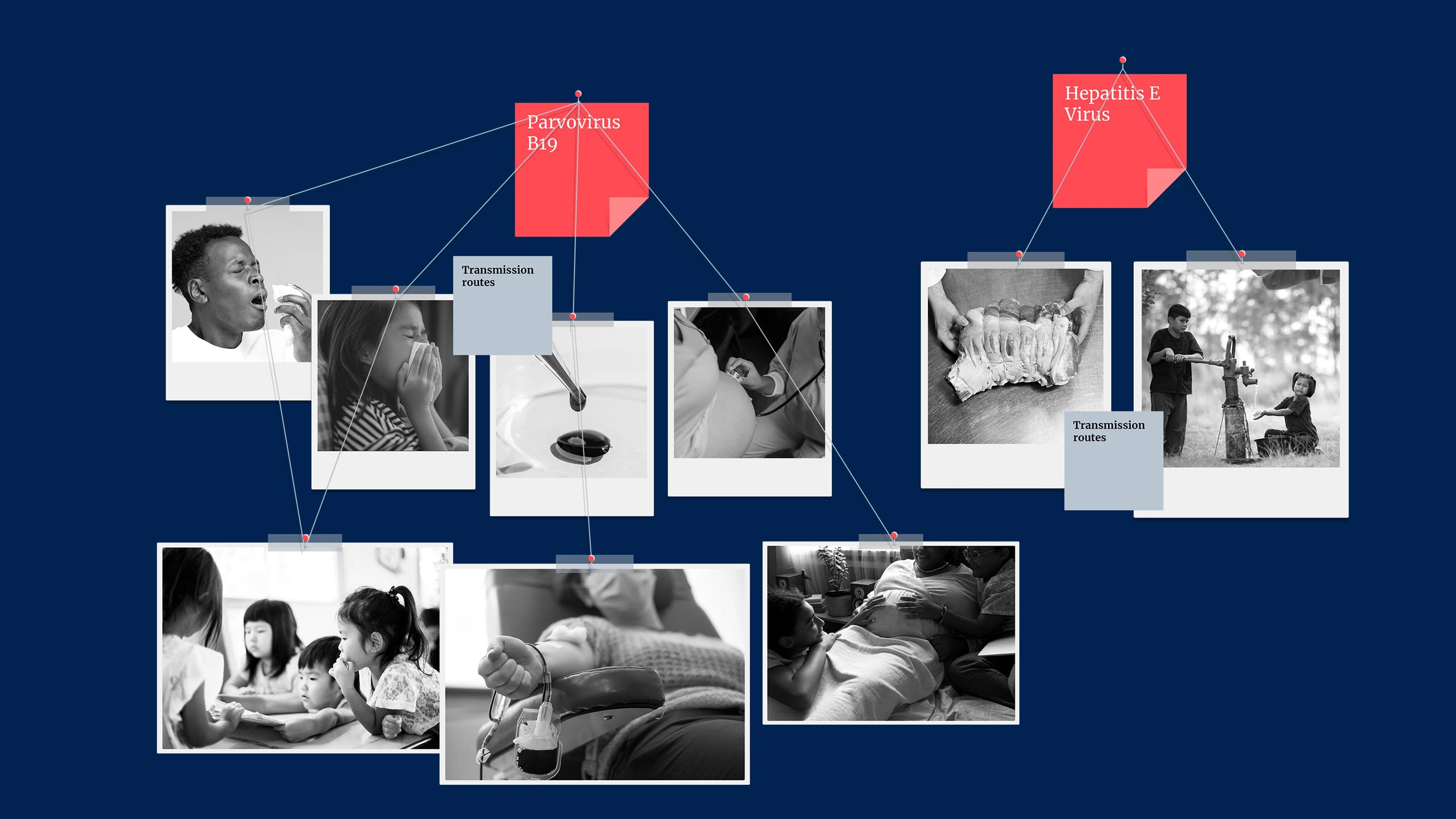

Parvovirus B19 needs no accomplices. It is transmitted primarily through respiratory droplets from coughs and sneezes—very common in places where there is frequent close contact between people such as nurseries, schools and daycare centres. The virus can also spread through blood and blood products, posing a risk for people who undergo transfusions or organ transplants. In pregnant women, Parvovirus B19 can cross the placenta from an infected mother to her unborn child, potentially leading to severe complications such as miscarriage.

Similarly, Hepatitis E uses no accomplices to spread from person to person. It generally spreads via the so-called faecal-oral route. In countries with poor sanitation, people most often get hepatitis E from drinking water contaminated with faeces from people infected with the virus. In other countries where sanitation is good and Hepatitis E is not as common, those who do become infected generally do so after eating raw or undercooked pork, venison (deer meat), wild boar meat or shellfish.

Common Victims

While Parvovirus B19 can infect anyone of any age or gender, it is particularly dangerous for women who are pregnant and for their unborn babies. Infection with the virus during pregnancy can lead, in some cases, to serious anaemia in the baby, miscarriage or a condition known as hydrops foetalis in which large amounts of fluid build up in a baby's tissues and organs, causing severe swelling.

Similarly, pregnant women infected with Hepatitis E Virus, particularly in the second or third trimester, are at increased risk of miscarriage, acute liver failure or death. Hepatitis E infection is fatal in up to 30 percent of infected pregnant women in the third trimester.

Infamous Outbreaks

Parvovirus B19

Parvovirus B19 is fairly common worldwide, with the majority of its victims barely noticing their symptoms or getting only mildly ill. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Prevention and Control, about 50 percent of adults globally have detectable B19 antibodies by the age of 20, meaning the virus has infected them in the past. This increases to more than 70 percent in adults aged 40.

In 2024, disease trackers in the United States, Japan and Europe all reported increases in cases of Parvovirus B19, with clusters of complications in vulnerable groups such as pregnant women and people with compromised immune systems.

In the U.S., health authorities said the most significant increase in prevalence was among children aged between five and nine years old—from 15 percent during 2022 to 2024 to 40 percent in June 2024. Meanwhile in Japan, authorities reported the worst outbreak of Parvovirus B19 in 25 years, with particular risks to pregnant women.

Hepatitis E

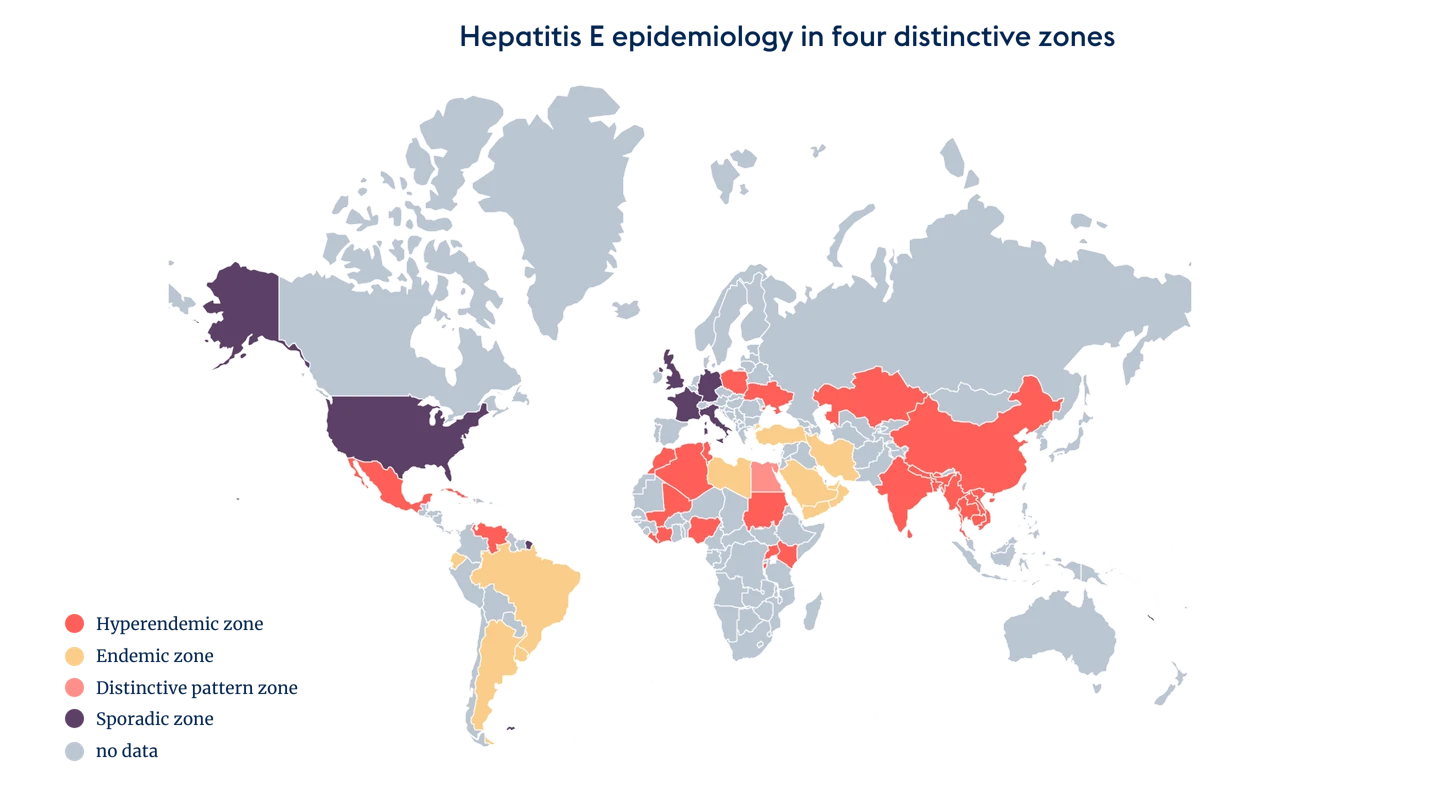

Hepatitis E infection is also found worldwide, but outbreaks are more common in low- and middle-income countries where access to water, sanitation, hygiene and health services is limited. The World Health Organization estimates there are 20 million Hep E infections a year worldwide, leading to an estimated 3.3 million symptomatic cases.

While Hep E can attack in sporadic cases, it does so more often in clusters or outbreaks. These outbreaks, which may affect several hundred to several thousand people at a time, typically come amid natural disasters, conflict or other humanitarian emergencies when there is a higher risk of drinking water contamination or poor sanitation.

Adapted from Aziz, A. et al. (2022). Hepatitis E Virus (HEV): Synopsis, General Aspects, and Focus on Bangladesh. Viruses

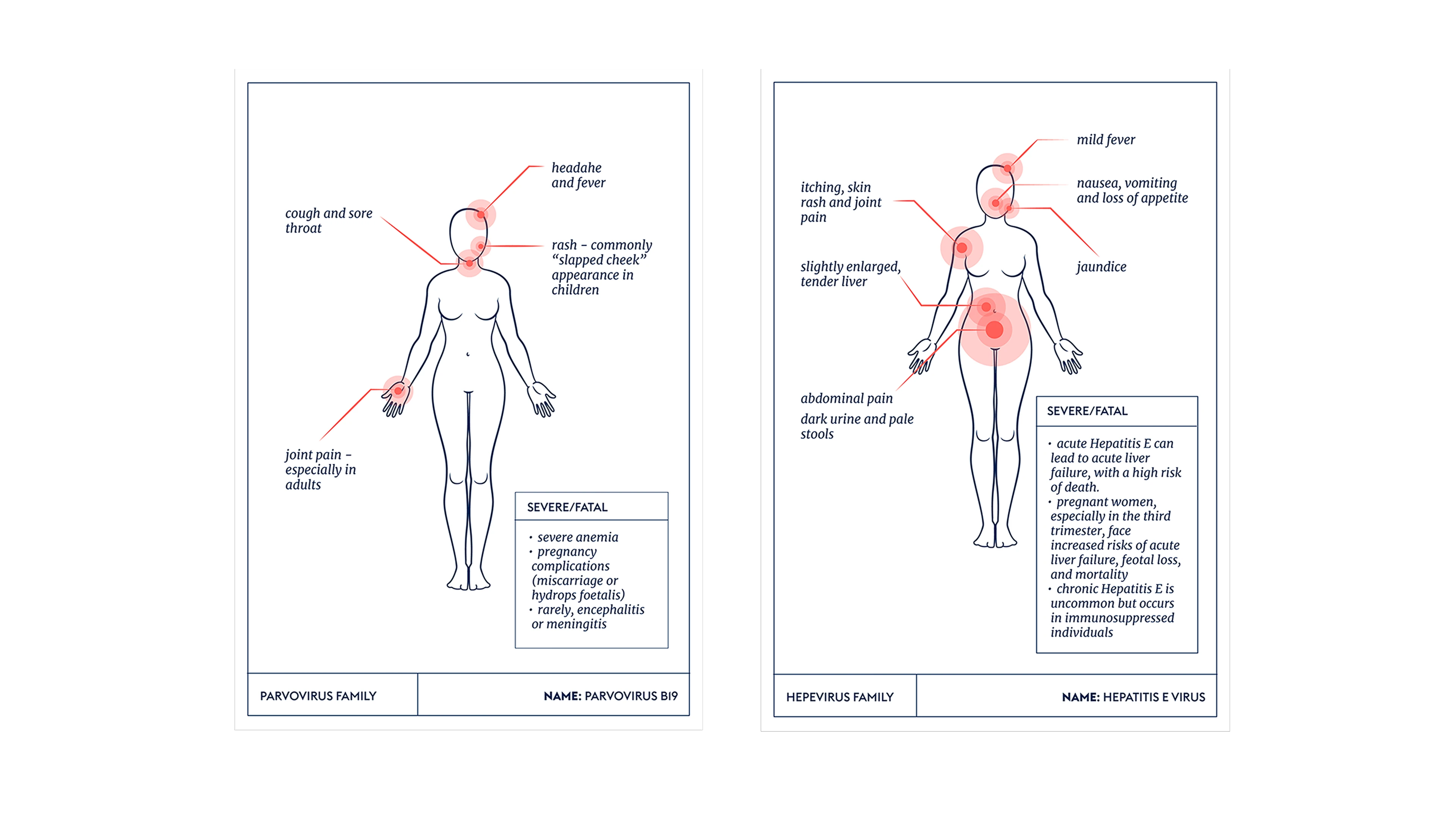

Common Harms

In most people, Parvovirus B19 causes mild symptoms such as fever, headache, sore throat, and a distinctive "slapped cheek" rash in children. Adults infected with the virus may also get joint pain and swelling, particularly in the hands, wrists, knees and ankles. In rare cases, Parvovirus B19 can cause severe anaemia, and in women who are pregnant it can increase the risk of having a miscarriage or stillbirth.

Many victims of Hepatitis E infection do not suffer any obvious harm and most recover quickly. Others may have one or more mild symptoms, including dark urine, clay-coloured stools, fatigue, joint pain, fever, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting and a yellowing of the skin or the eyes. In pregnant women, however, Hepatitis E can be severe and has been linked to up to 30 percent mortality in the third trimester. The infection can also cause miscarriage, stillbirth, pre-term births, and can sometimes be passed from mother to baby.

Lines of Enquiry

Scientists have been pursuing various lines of enquiry over the past few decades into ways to prevent or treat Hepatitis E infection. This has resulted in the development of one type of vaccine for Hepatitis E, but it is currently only available in China.

There are currently no vaccines or specific treatments licensed or recommended for Parvovirus B19 infection but scientists are exploring various approaches, including developing potential vaccines that use mutated virus-like particles (VLP).

Editor's note:

The naming and classification of viruses into various families and sub-families is an ever-evolving and sometimes controversial field of science.

As scientific understanding deepens, viruses currently classified as members of one family may be switched or adopted into another family, or be put into a completely new family of their own.

CEPI’s series on The Viral Most Wanted seeks to reflect the most widespread scientific consensus on viral families and their members, and is cross-referenced with the latest reports by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).

Related articles

Related articles

The Arenaviruses

The Arenavirus family includes some of the most lethal haemorrhagic fevers known. All its prime suspects can cause life-threatening disease and death

The Flaviviruses

Yellow Fever is now known as one of several deadly viral haemorrhagic fevers currently classified a Flavivirus, one of The Viral Most Wanted.

The Paramyxoviruses

This family contains one of the most contagious human viral diseases, as well as one of the most deadly. Explore The Paramyxoviruses.

Matonaviruses and Togaviruses

Multiple lines of enquiry against Chikungunya virus and its viral relatives are being pursued by scientists around the world, with the hope for a new protective vaccine coming very soon.

The Nairoviruses

The prime suspect in this family is a deadly virus that causes its human victims to bleed profusely.

The Poxviruses

The viral family of one of the most fearsome contagious diseases in human history

The Hantaviruses

Some Hantaviruses focus their attacks on blood vessels in the lungs, causing the blood to leak out and ultimately ‘drowning’ their victims.

The Retroviruses

The most nefarious Retrovirus—HIV—has infected 85 million and killed 40 million people worldwide.

The Filoviruses

“one of the most lethal infections you can think of” - and it's one whose deadly reach is extending ever further

The Orthomyxoviruses

These viral culprits have caused the deadliest pandemics in human history

The Picornaviruses

Large, persistent and deadly outbreaks of a crippling infection caused by one member of this viral family meant that it was once among the most feared diseases in the world

The Phenuiviruses

The most infamous Phenuivirus, Rift Valley fever, poses a significant threat to people and livestock causing serious disease and dangerous outbreaks.