The Paramyxoviruses

In the late 1990s, Malaysia’s pig population had reached several million. Driven by increasing demand for pork meat, farmers expanded their capacity so that some of them had tens of thousands of pigs on sprawling sites that encroached on the region’s tropical rainforests. Keen to make as much as they could from working their land, some planted orchards of date palms and mango trees too.

Yet as the farmers prospered, the local wildlife was forced to adapt. Flying fox fruit bats that once feasted on wild fruit in the forests found that, with their natural habitat shrinking, they had to forage for food in the commercial farms and orchards.

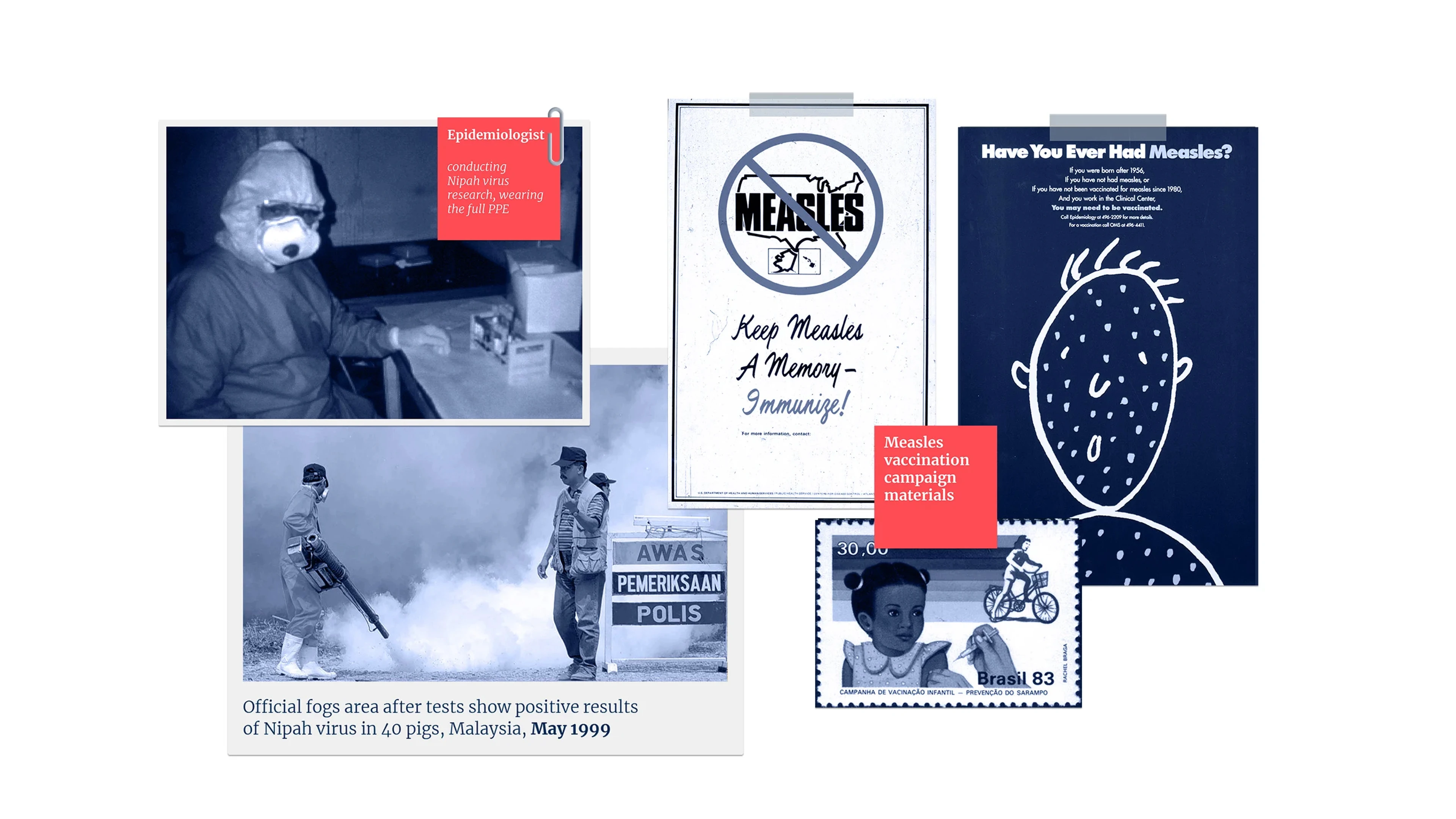

This was how in 1998, on one particular farm in the town of Kampung Sungai Nipah, a fruit bat carrying a virus was able to pass it on to pigs who ate its leftovers. And how, in turn, the pigs who ate the contaminated fruit scraps were able to pass that same virus on to farm workers. Several of them became sick with a mysterious and frightening illness that sent their bodies into fevers and fits, before penetrating and inflaming their brains.

The virus that produced these devastating symptoms, identified by scientists in 1999 and named Nipah after the village where it first appeared, is currently classified as a member of the Paramyxovirus family, one of The Viral Most Wanted.

One Big Close-Knit Family?

Big – yes, but not particularly close. The Paramyxovirus family has more than 75 viruses, most of which are within two distinct sub-groups. The first of these is called the Paramyxoviruses and the second is called the Morbillivirus group. While the sub-groups groups are related, they have very distinct members with distinct ways of operating.

Prime Suspects

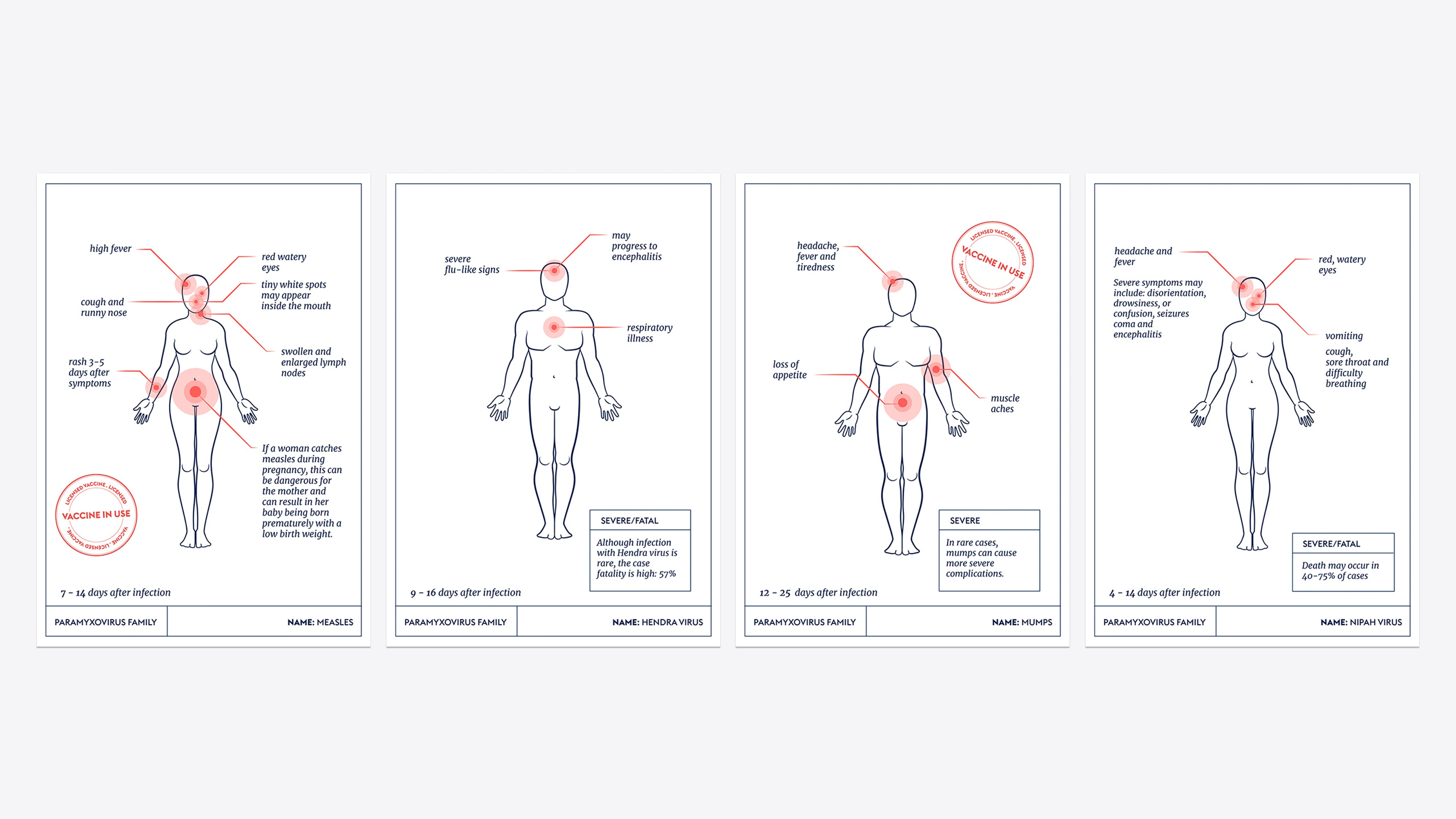

The Paramyxovirus family has several prime suspect pathogens that are known to cause a wide range of diseases in people and in animals. Some of the most threatening Paramyxoviruses to humans include Hendra virus, Measles, Mumps, Nipah virus, and Parainfluenza viruses.

Nicknames and Aliases

The family name Paramyxovirus comes from the Greek “para”, meaning “by the side of”, and “myxa” meaning “mucus”.

The name Nipah comes from Kampung Sungai Nipah – the village in the Malay Peninsula where it first emerged in humans.

When Measles was first described in medical literature – in the 10th Century by the Persian physician Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyāʾ al-Rāzī, often known by his Latin name Rhazes – it was called “basba”, which simply means “eruption”. The modern name Measles comes from an ancient Arabic word, “miser”, which means the "unhappiness of lepers." Measles was also historically sometimes known as "little leprosy”.

Hendra virus is named after a suburb of Brisbane, Australia, where it was first identified in humans at a stables where 21 horses and two people became infected with what had previously been referred to only as a “newly described Morbillivirus”.

Distinguishing Features

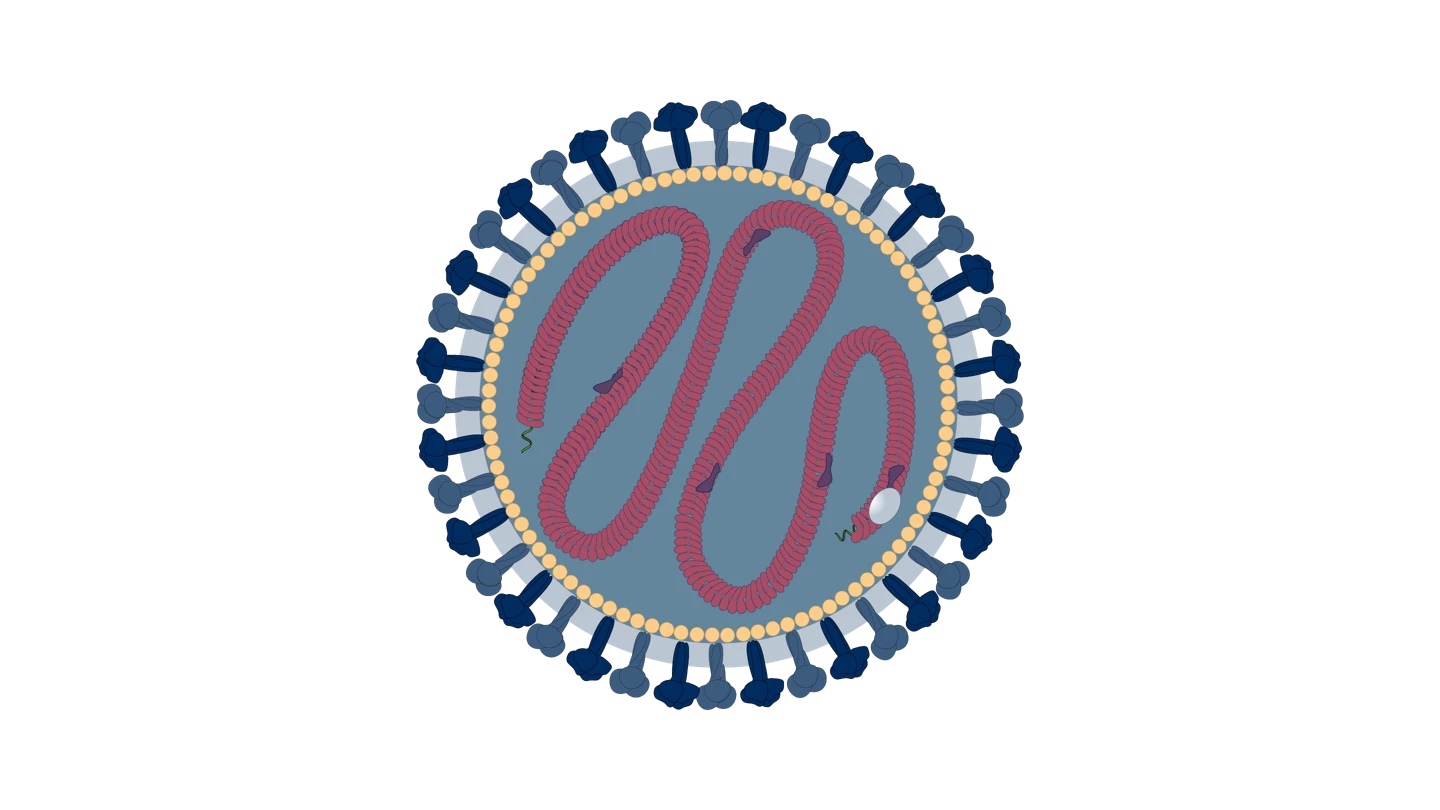

Paramyxoviruses are tiny, spherical or irregular spherical enveloped virus particles, or virions, of about 150 to 300 nanometres in diameter. The inner capsid – which contains the single-stranded RNA genome – is surrounded by a double-layered lipid membrane, and spikes containing proteins protrude from the membrane.

Modus Operandi

Paramyxoviruses generally enter and infect a host’s cells by using a “fusion protein”, known as F, and an “attachment protein”, which would be either H, HN or G, depending on the type of Paramyxovirus.

One of the reasons that Nipah virus is considered such a serious potential threat is its ability to infect cells that have ephrin-B receptors – receptors that regulate what gets in or out of cells that line the central nervous system and vital organs. Because all mammals have cells with these or similar receptors, Nipah is able to infect many of them, including humans.

Accomplices

Some Paramyxoviruses need no accomplices to spread. The Mumps virus spreads in droplets, while the Measles virus is airborne, meaning it can pass from person to person even when there is no physical contact between them at all. Measles is also able to ‘hang’ in the air for several hours, rather than falling to the ground in droplets, adding to its ability to invisibly infect multiple victims.

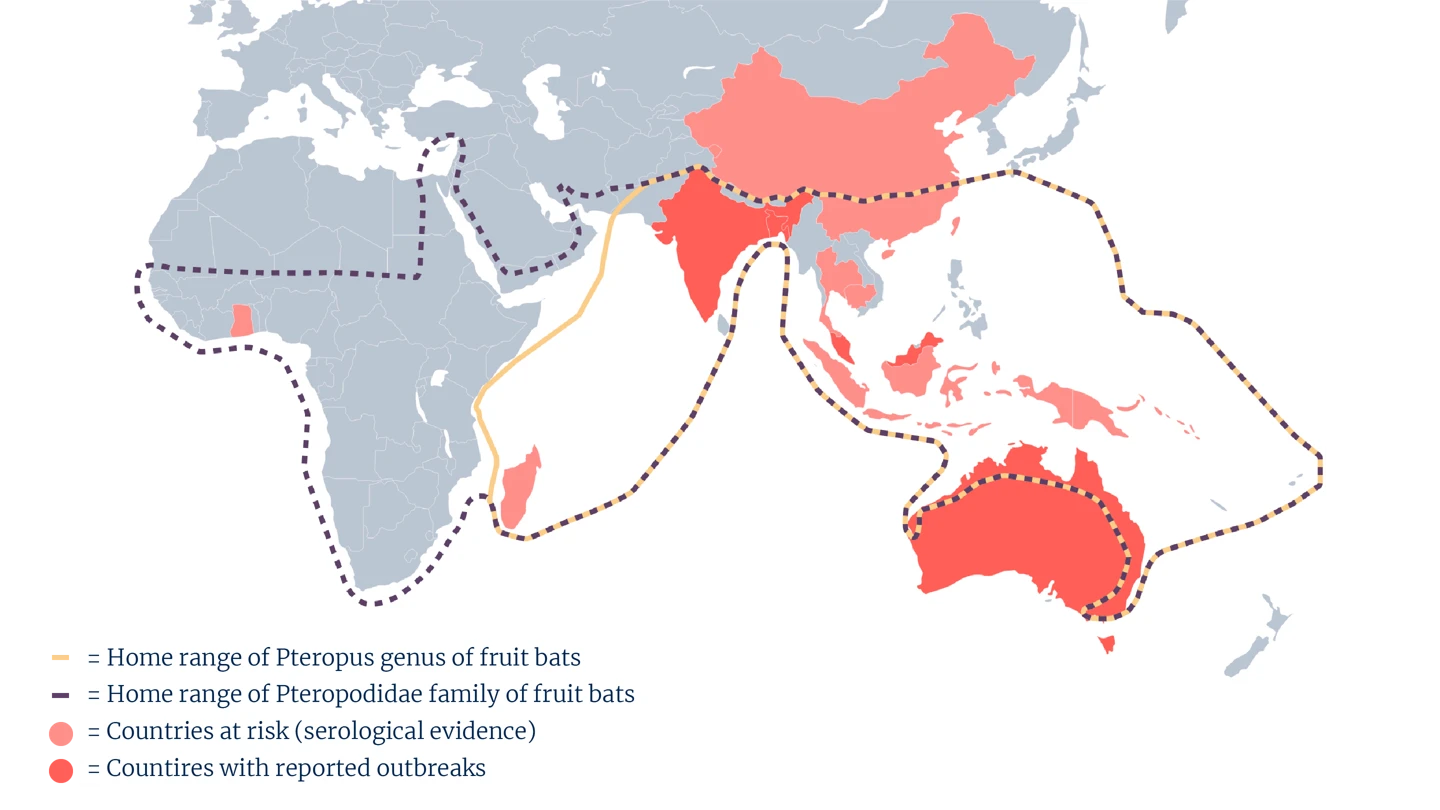

Bats are the key accomplices of Nipah virus and Hendra virus, but both have been known to use secondary accomplices too. In some human Nipah outbreaks, including the first one in Malaysia in 1999, pigs were an intermediate conduit of the virus from bats to people. Hendra virus has so far only been found to infect humans after it has first passed through horses. Horses become infected with Hendra after exposure to urine, droppings or saliva of an infected flying fox bat.

Common Victims

Measles is the most contagious human viral disease ever known, and can infect anyone who does not have immunity from being vaccinated or from being previously infected. Babies and young children, as well as women who are pregnant, are at highest risk of severe Measles complications. These can include life-threatening pneumonia and swelling of the brain. Animals do not get or spread Measles.

Human Parainfluenza viruses cause around 30 to 40 percent of all acute respiratory infections in babies and children. Parainfluenza viruses also infect dogs, horses, cows, sheep, goats and some birds, such as pigeons.

Nipah virus is carried by bats, which do not seem to get sick from it but can carry the virus across regions and continents as they excrete it in their droppings and other bodily fluids. Pigs infected with Nipah do get sick, and it is highly pathogenic in people. Because of the Nipah virus’ modus operandi – including its ability to attach to cells that are common in many species – disease detectives suspect many different types of animals are vulnerable to Nipah infection.

Hendra virus primarily infects horses and has so far been found only in Australia. Human cases of infection with Hendra virus in people are very rare, but they are possible and extremely dangerous. The fatality rate for Hendra in people is 57 percent among the small number of cases so far identified.

Mumps virus infects monkeys, rabbits, dogs, cats, and rodents as well as people.

Infamous Outbreaks

Measles

Measles has caused multiple serious epidemics of disease all around the world over the last 100 years. Despite dramatic progress brought about by effective national immunisation programmes in many countries, the disease is still endemic in large parts of Asia, Africa and the Middle East and has only been eliminated in very few countries.

Even in 2023, the Measles virus has so far already infected tens of thousands of people in India and Yemen, and many thousands more in Pakistan, Nigeria, Indonesia and Cameroon.

Some of the most serious Measles epidemics in recent years include a devastating outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo during 2019 and 2020, in which 341,000 people - many of them children – were infected, and 6,400 of them died. Another viral disease – Ebola – was also causing a deadly outbreak in DRC at the same time.

Nipah

The Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia in 1998 and 1999 was the earliest known outbreak. It primarily affected pig farmers and those in close contact with infected pigs. The outbreak resulted in several deaths and led to the culling of thousands of pigs to control the spread.

Nipah has since 2001 also caused multiple outbreaks in Bangladesh, often in rural areas where the flying fox fruit bats that carry the virus are common, and where people have become infected after eating contaminated sap or fruit from date palms.

Among the deadliest outbreaks of Nipah came in India in 2001, when 66 people were reported as infected and 45 of them died. This was the first Nipah outbreak in India and, worryingly, it has since been followed by several more: one in 2007 which killed five people, another in 2018 which killed 17, and another in 2021 in which one person – a 12-year-old boy – died after contracting Nipah virus disease. In September 2023, another outbreak of Nipah virus infections was reported in the southern Indian state of Kerala.

Infamous Outbreaks

Mumps

Like Measles and several other vaccine-preventable Paramyxoviruses, the Mumps virus continues to cause multiple large outbreaks of disease in many countries around the world. In 2022, Senegal reported more than 125,000 cases of the disease, accounting for almost a third of all global cases in that year. Mumps outbreaks were also reported in China, Zambia, Ghana, and Madagascar in 2022.

Common Harms

Measles can be mild, but in severe cases can also cause pneumonia, blindness, deafness, brain damage or death. An estimated 128,000 people died from Measles in 2021 – mostly children younger than five years old.

The spectrum of disease caused by Parainfluenza virus infection in babies and young children ranges from a mild, febrile, common cold-type illness to severe, potentially life-threatening croup, bronchiolitis, and pneumonia.

Hendra virus infection in horses and humans can cause severe respiratory and neurological symptoms and has an extremely high mortality rate. Approximately 80 percent of horses and 60 percent of people infected with Hendra virus die. Hendra is extremely rare, however, with a total of only seven human cases reported since the disease was first identified in humans in 1994.

Mumps is a systemic infection that can cause high fever and painful swelling of the parotid glands at the side of the face under the ears. People infected with Mumps can often have a distinctive 'hamster face' appearance. In severe cases, infected victims can suffer pancreatitis, deafness, swelling of the brain – known as encephalitis - and meningitis. Adults infected with Mumps can also suffer with inflammation of the testes or ovaries.

Nipah virus infection can start with mild symptoms such as headache, muscle pain, fatigue and nausea. It can progress to difficulty with breathing and other deadly symptoms as the disease advances and gets into the brain. Here, Nipah victims can suffer confusion, seizures and encephalitis, and as many as 75 percent of those infected die.

Among people who recover from Nipah virus infection, long-term harms include severe psychiatric conditions such as depression, personality changes and loss of verbal and visual memory.

Lines of Enquiry

Disease prevention scientists developed highly effective vaccines against several members of the Paramyxovirus family, including the most prolific threats – Measles and Mumps – in the 1960s. Widespread use of these vaccines, which offer lifelong protection from infection to people immunised with them, has helped limit the spread, size and frequency of Measles and Mumps outbreaks over the past 50 years.

Fast and targeted work by disease detectives on the Hendra and Nipah viruses is also yielding promising progress in efforts to one day be able to prevent people from becoming infected with these killer viruses. A vaccine to prevent Hendra virus infection in horses has been available since November 2012, but a vaccine against human infection has yet to be developed.

For Nipah virus, multiple teams of investigators are working on different approaches to developing a protective vaccine. CEPI has supported four early-stage Nipah vaccine candidates, two of which are in active development, and has also invested in the development of a Nipah virus monoclonal antibody (mAb).

Other important lines of enquiry in Nipah investigations are CEPI-supported studies being conducted in Bangladesh and Malaysia with some of the very few survivors of the often fatal disease. Disease detectives are exploring various aspects of the survivors’ immune systems in the search for clues about how treatments or vaccines could bolster the human body’s response to Nipah infection.

The historical successes in Mumps and Measles vaccine development, together with significant advances against Nipah and Hendra, have energised researchers working on this deadly and diverse viral family and given hope that human defences could one day be available against all its prime suspect members.

Editor's note:

The naming and classification of viruses into various families and sub-families is an ever-evolving and sometimes controversial field of science.

As scientific understanding deepens, viruses currently classified as members of one family may be switched or adopted into another family, or be put into a completely new family of their own.

CEPI’s series on The Viral Most Wanted seeks to reflect the most widespread scientific consensus on viral families and their members, and is cross-referenced with the latest reports by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).