The Rhabdoviruses

When the great philosopher, scientist and teacher Aristotle wrote about zoology in his History of Animals in around 350 B.C.E, he described dogs as suffering from three distinct diseases. Among these was a particularly grim one that “produces madness”, he wrote. The mania-inducing disease also developed “in all animals that the dog has bitten”, Aristotle observed, and then “kills them” and “kills the dogs too”.

This ancient text is one of the earliest known descriptions of what is now considered one of the oldest known zoonotic diseases—Rabies.

As a zoonosis—a disease that made a species jump from dogs and other animals to people—Rabies has hounded the history of human health for thousands of years. Before modern vaccines and post-exposure treatments, it was feared as a virus that could render even a small bite or scratch from a dog or other rabid animal universally fatal. Historical accounts reported that people were sometimes so scared of being bitten by a rabies-carrying animal they would rather take their own lives than face the risk.

This fearsome, death-sentence of a disease is caused a pathogen known as Rabies Lyssavirus, the most notorious member of the Rhabdovirus family—one of the Viral Most Wanted.

Big Close-Knit Families?

There are more than 140 different viral species within the Rhabdovirus family, but only a handful of them are known to cause human disease. While they are part of the same family, these human-disease causing Rhabdoviruses are not particularly closely related, since they belong to different subgroups, such as the Lyssavirus subgroup and the Vesiculovirus subgroup. They do however share some similar structural features that play an important role in enabling them to get into and infect host cells.

Prime Suspects

The number one suspect in this viral family is Rabies Virus, also known as Rabies Lyssavirus. Other key Rhabdovirus culprits in terms of human infection and disease are Vesicular Stomatitis Virus, Bas Congo Virus and Chandipura Virus.

Nicknames and Aliases

The family name Rhabdovirus derives from the Ancient Greek word “rhabdos” meaning "rod", which refers to the elongated bullet shape of the viral particles.

The name of the family’s prime suspect, Rabies Lyssavirus, is also derived from a Greek word—“lyssa” meaning violent—as well as the Latin “rabies”, which means "madness” or “rage” or “fury” and describes the crazy and aggressive behaviour seen in animals infected with the disease.

Historically, Rabies was sometimes referred to as “canine madness”, because it appeared to make its victims deranged after they had been bitten by a dog. It was also known as "hydrophobia" because one of the characteristic symptoms of the disease is a fear of water caused by painful spasms in the throat muscles when trying to drink.

Chandipura Virus is sometimes called Chandipura Vesiculovirus, or CHPV. It is named after the Chandipura village in Maharashtra State in India, where it was first discovered during an outbreak of encephalitis in 1965.

Vesicular Stomatitis Virus, which was first identified in Indiana in the United States in 1925, is also known by several aliases, including Indiana Vesiculovirus and Vesicular Stomatitis Indiana Virus.

Distinguishing Features

Disease detectives say Rhabdoviruses are very distinct and easily recognisable under an electron microscope, mainly because they are bullet-shaped. Rhabdovirus virions, or virus particles, are usually about 75 nanometres wide and around 180 nanometres long.

Source: Viral Zone by SwissBioPics

Modus Operandi

The Rhabdovirus family’s prime suspect, Rabies Lyssavirus, typically gets into a human victim’s body through a bite or scratch from an infected animal, which introduces the virus into muscle tissues. It then travels very slowly along the peripheral nerves towards the central nervous system, using the neuron's own transport machinery to move. The Rabies Lyssavirus can spend many days, weeks or even months in a victim’s body before it gets into the nervous system. Once it has made it into the central nervous system, the virus multiplies and spreads to the brain and the spinal cord where it causes neurological damage, and to the salivary glands where it makes its victims drool or “foam at the mouth”.

Accomplices

In up to 99 percent of cases of human infection with Rabies, dogs are the number one accomplice. But bats, racoons, foxes, skunks and other animals can also pass it on through scratches or bites.

Chandipura Virus uses sandflies—specifically from the species Phlebotomus—as its main accomplices in infecting people. Vesicular Stomatitis Virus, which is primarily a disease of cattle, horses and pigs but can also infect people, is spread through direct contact with infected animals or with their saliva or other body fluids.

Common Victims

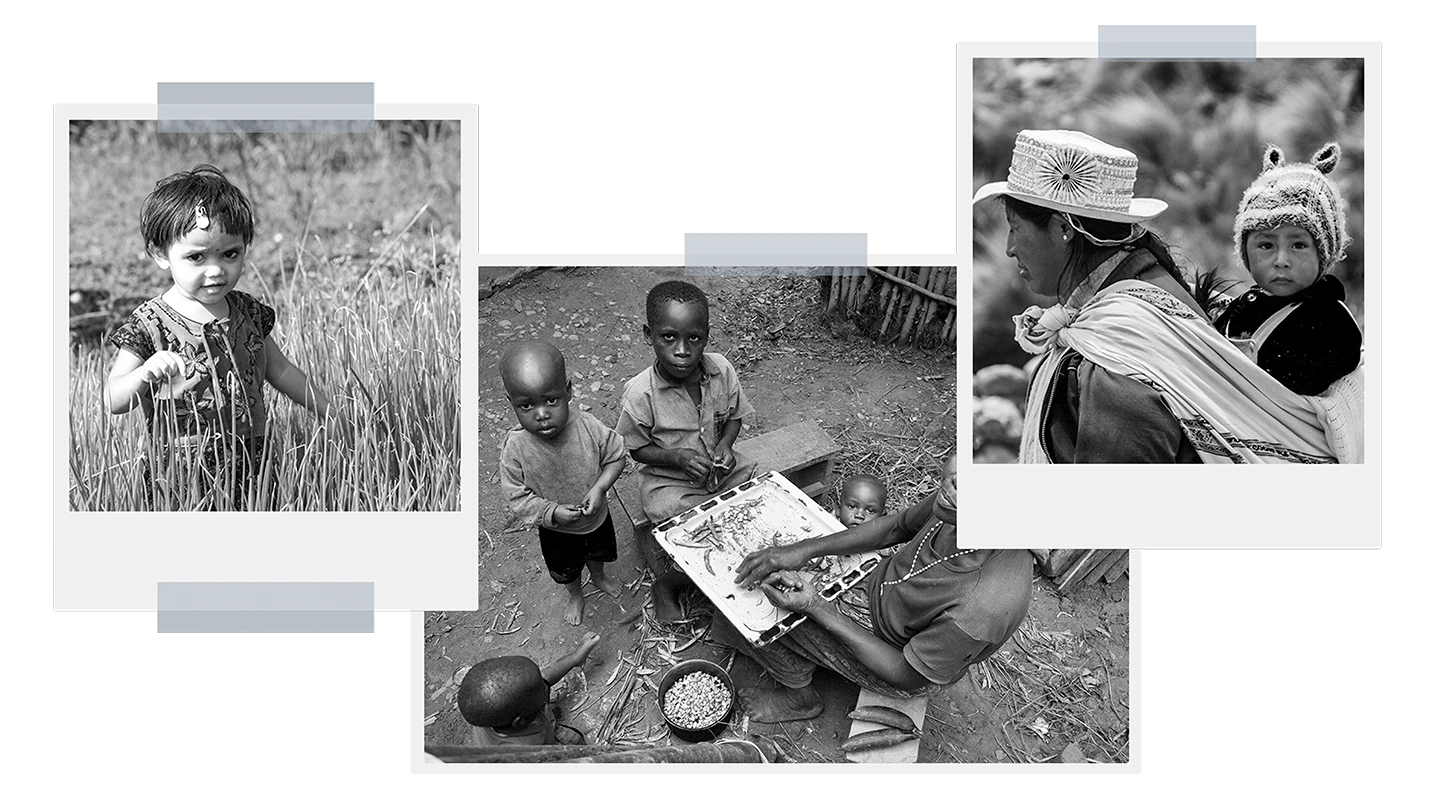

Children aged between four and 15 years are by far the most common victims of Rabies Lyssavirus attacks—mostly because they are more likely to be bitten by infected dogs while out playing in the streets and parks. Of the estimated 59,000 deaths from Rabies around the world each year, around 40 percent are children younger than 15.

While people living on all continents of the world except Antarctica are at risk of being exposed to Rabies, it poses the greatest threat among marginalised communities of people who live in areas with high populations of stray dogs and in lower-income countries in parts of Africa and Asia.

The most common victims of Chandipura Virus are also children under the age of 15, and especially those under 10 years, in part because babies and small children have immature immune systems that are less able to fight off a viral attack. This Rhabdovirus predominantly affects children in rural or semi-urban areas, where sandflies are more common.

Infamous Outbreaks

Rabies

India has the highest rate of human Rabies infections in the world, primarily because it has high numbers of stray dogs. According to World Health Organization figures, the virus kills between 8,000 and 20,000 people in India every year, many of them children.

Historically, Rabies was also extremely common and deadly in China, with more than 5,200 deaths a year reported between 1987 and 1989.

One of the most notable outbreaks of Rabies in the United States was in New Jersey in 1885, when four boys were bitten by a dog suspected to be rabid. A local doctor recommended that the boys be sent to Paris to receive a vaccine that Louis Pasteur had used successfully for the first time in a person just a few months earlier. This event marked the beginning of international efforts to try to control and cure Rabies infections in people.

Rabies is now largely under control in the U.S, but in 2021 five people died there after contracting the disease from bats— the highest annual number human Rabies deaths in the U.S. in a decade.

In the United Kingdom, the last recorded case of indigenous Rabies in a person was in 1902, while the last case of indigenous animal rabies was recorded 20 years later. Since 1946 there have been only 22 deaths from Rabies in the UK, all of them in people who were infected while in another country.

Source: World Health Organization, Global Health Observatory: Rabies

Chandipura Virus

Among the most notorious outbreaks of Chandipura Virus were in 2003 and 2004 in the central Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra and Gujarat. A total of 322 children were killed by the virus across the affected areas, with case fatality rates of 56 percent in Andhra Pradesh and 75 percent in Gujarat. In many of the cases, the victims died within 24 hours of their first symptoms.

Common Harms

Rabies kills the vast majority of its victims, unless it is treated extremely quickly. The virus’s initial harms to its human victims can be very similar to those of any generic viral illness—with fever, malaise and headache. These mild effects then advance to anxiety, agitation and eventually to delirium. A common symptom after a rabid bite is tingling at the site of the wound within the first few days. Once Rabies Lyssavirus has moved from its victim’s peripheral nerves to the central nervous system, it travels back to the peripheral nervous system, mainly targeting body areas with high concentrations of nerves, such as the salivary glands. The "frothing at the mouth" depicted in movies featuring Rabies cases is due to a symptom known as hypersalivation, and sufferers can experience severe spasms in the throat at the mere sight, taste or sound of water—a phenomenon called hydrophobia.

Chandipura Virus infection also typically begins with nonspecific symptoms that can easily be mistaken for other viral infections, but then very rapidly progresses to include the sudden onset of high fever, intense headache, sensitivity to light, persistent vomiting, dehydration, confusion, irritability, and excessive drowsiness. In severe Chandipura cases, seizures are common, and in extreme cases the infection leads to coma and death.

Lines of Enquiry

Disease detectives’ work on developing vaccines against the Rabies Rhabdovirus has been extremely successful. In preventing human Rabies deaths, that success began in 1885 in the French town of Alsace, when a nine-year-old boy, Joseph Meister was bitten multiple times by a rabid dog. Knowing her child was facing almost certain death and with no treatment options available, Meister’s mother decided to take him to Paris to see the celebrated scientist Louis Pasteur, whom she had heard had been experimenting with vaccinating animals against Rabies. Pasteur agreed to try the experimental vaccine, and after a two-week-long-series of daily injections, Meister’s recovery marked the first successful use of a Rabies vaccine in people.

Following Pasteur’s success, scientific enquiry led to the first wave of Rabies vaccines being developed using nerve tissue from infected animals. While these early vaccines were effective, they also had significant side effects, prompting scientists to make further progress in the mid-20th century to develop safer cell-culture-based vaccines. These products, such as the human diploid cell vaccine (HDCV) and purified chick embryo cell vaccine (PCECV), then became the standard for Rabies prevention . Rabies vaccines can be used prophylactically to prevent infection in people who are at high risk of being bitten by a dog or other rabid animal, or as post-exposure prophylaxis immediately after someone has been bitten by an infected animal.

In recent decades, Rabies vaccination evolved yet further, with highly effective modern vaccines now being used with minimal side effects. Global vaccination programmes in both people and dogs have helped to significantly reduce Rabies cases in many countries, but this Rhabdovirus remains a major killer—especially of poor and marginalised children—in some parts of the world.

Editor's note:

The naming and classification of viruses into various families and sub-families is an ever-evolving and sometimes controversial field of science.

As scientific understanding deepens, viruses currently classified as members of one family may be switched or adopted into another family, or be put into a completely new family of their own.

CEPI’s series on The Viral Most Wanted seeks to reflect the most widespread scientific consensus on viral families and their members, and is cross-referenced with the latest reports by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).

Related articles

Related articles

The Arenaviruses

The Arenavirus family includes some of the most lethal haemorrhagic fevers known. All its prime suspects can cause life-threatening disease and death

The Flaviviruses

Yellow Fever is now known as one of several deadly viral haemorrhagic fevers currently classified a Flavivirus, one of The Viral Most Wanted.

The Paramyxoviruses

This family contains one of the most contagious human viral diseases, as well as one of the most deadly. Explore The Paramyxoviruses.

Matonaviruses and Togaviruses

Multiple lines of enquiry against Chikungunya virus and its viral relatives are being pursued by scientists around the world, with the hope for a new protective vaccine coming very soon.

The Nairoviruses

The prime suspect in this family is a deadly virus that causes its human victims to bleed profusely.

The Poxviruses

The viral family of one of the most fearsome contagious diseases in human history

The Hantaviruses

Some Hantaviruses focus their attacks on blood vessels in the lungs, causing the blood to leak out and ultimately ‘drowning’ their victims.

The Retroviruses

The most nefarious Retrovirus—HIV—has infected 85 million and killed 40 million people worldwide.

The Filoviruses

“one of the most lethal infections you can think of” - and it's one whose deadly reach is extending ever further

The Orthomyxoviruses

These viral culprits have caused the deadliest pandemics in human history

The Picornaviruses

Large, persistent and deadly outbreaks of a crippling infection caused by one member of this viral family meant that it was once among the most feared diseases in the world

The Phenuiviruses

The most infamous Phenuivirus, Rift Valley fever, poses a significant threat to people and livestock causing serious disease and dangerous outbreaks.