The Papillomaviruses and Polyomaviruses

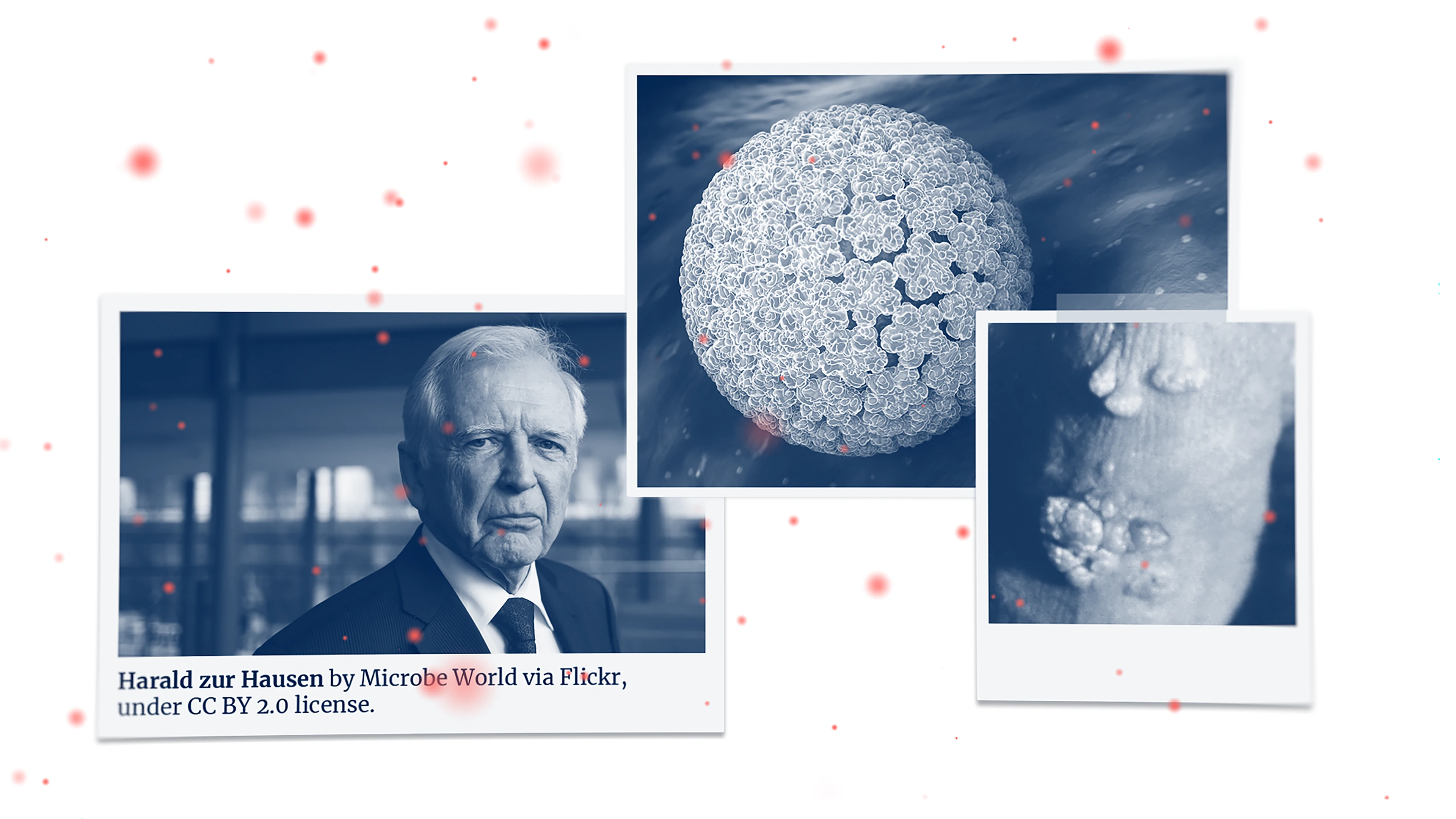

When he found out that some normally benign cases of genital warts could go rogue and become cancerous, the German scientist Harald zur Hausen began to think outside the box. While other scientists stuck firmly to the view that Herpes viruses were probably to blame, zur Hausen wondered whether other genital wart-causing pathogens might also trigger the development of cancerous tumours. So in 1972, when he was the head of a new clinical virology institute in Germany, he began investigating whether Human Papillomaviruses could be the culprits.

It took zur Hausen many years of persistent and dogged scientific work to prove that his thinking was correct, but by the mid-1980s he had definitively linked several strains of Human Papillomavirus to cancer of the cervix as well as cancers of the anus, penis, vagina, mouth and throat. In 2008, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine for this work, with judges praising him for pursuing his scientific idea for more than 10 years “against the prevailing view”.

The Papillomaviruses’ ability to cause cancer—referred to by scientists as oncogenic potential—is also shared by another family, the Polyomaviruses, and puts both families among The Viral Most Wanted.

One Big Close-Knit Family?

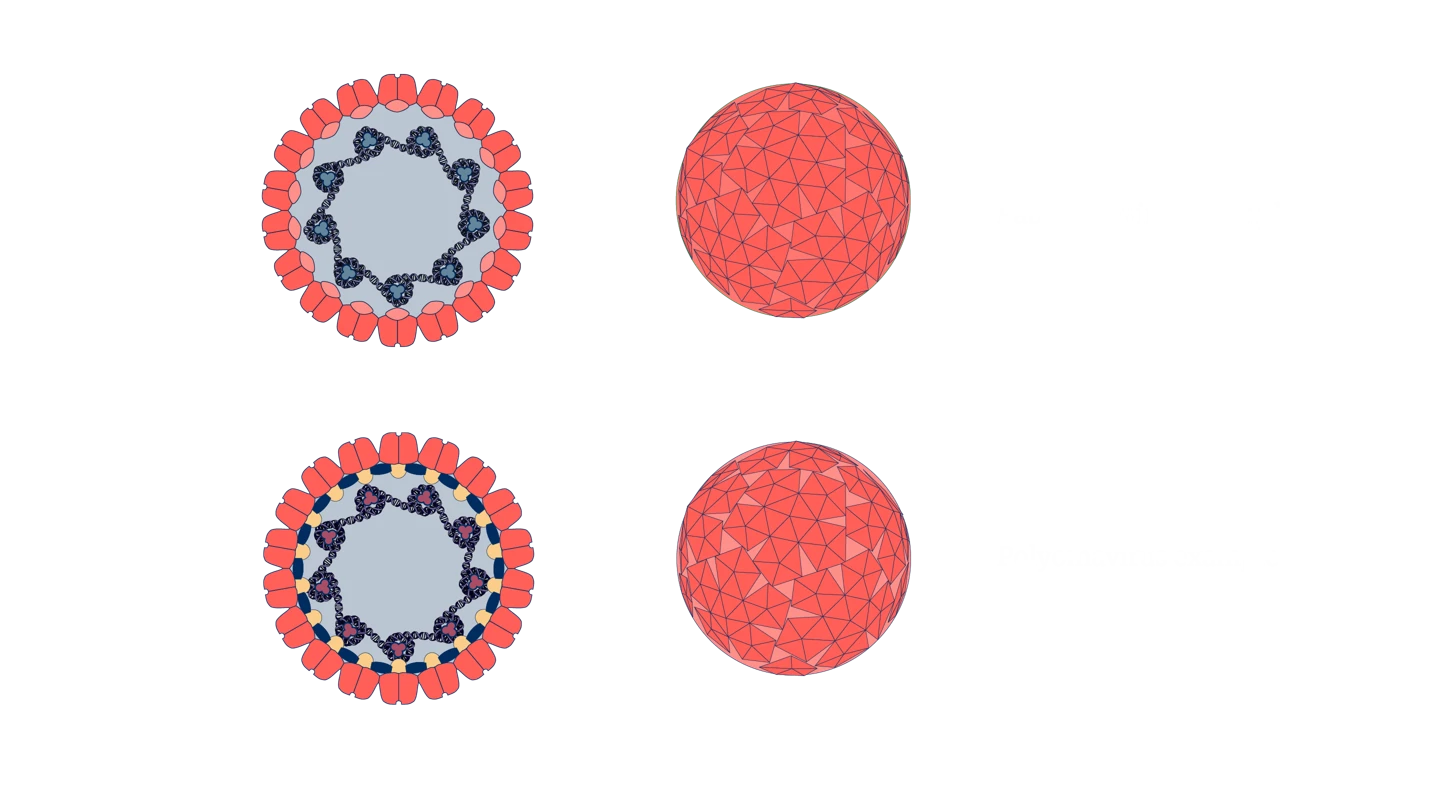

Previously yes – this was one big family. But the viral family formerly classified as the Papovaviruses is now obsolete and has been split into two distinct and growing families: the Polyomaviruses and Papillomaviruses.

Each of these viral families now includes hundreds of viruses, but only a proportion of their species and types are known to cause infections in people. Within the Human Papillomaviruses, for example, there are about 230 known and characterized types. While all of these can infect people, only around 14 of them are known to cause cancers. The Polyomavirus family is also large and has several subgroups, with 14 species believed to infect humans but only a handful of those linked to cancer and other severe diseases.

Prime Suspects

Within the Papillomavirus family, the most notorious pathogen is the Human Papillomavirus, often referred to as HPV, which is the cause of hundreds of thousands of cases of cancer in women and men around the world each year.

Among the Polyomaviruses, the biggest culprits are BK Virus, JC virus and Merkel Cell Virus, all of which are associated with rare but severe infections and some types of cancer in people with weakened immune systems.

Nicknames and Aliases

The name Papillomavirus derives from two Latin words—papillo, meaning “nipple”, and oma, meaning “tumour”—and describes the virus's ability to induce wart-like growths, or papillomas, on skin and mucous membranes. Similarly, the name Polyomavirus refers to the virus’s ability to produce multiple, or poly, tumours, or oma, in certain cases.

Distinguishing Features

Human Papillomaviruses are small, non-enveloped, icosahedral (20-sided) DNA viruses that have a diameter of around 52 to 55 nanometres.

Polyomavirus particles, or virions, are even smaller—with a diameter of around 40 to 45 nanometres—and are also non-enveloped, icosahedral DNA viruses.

Source: Viral Zone by SwissBioPics

Common Victims

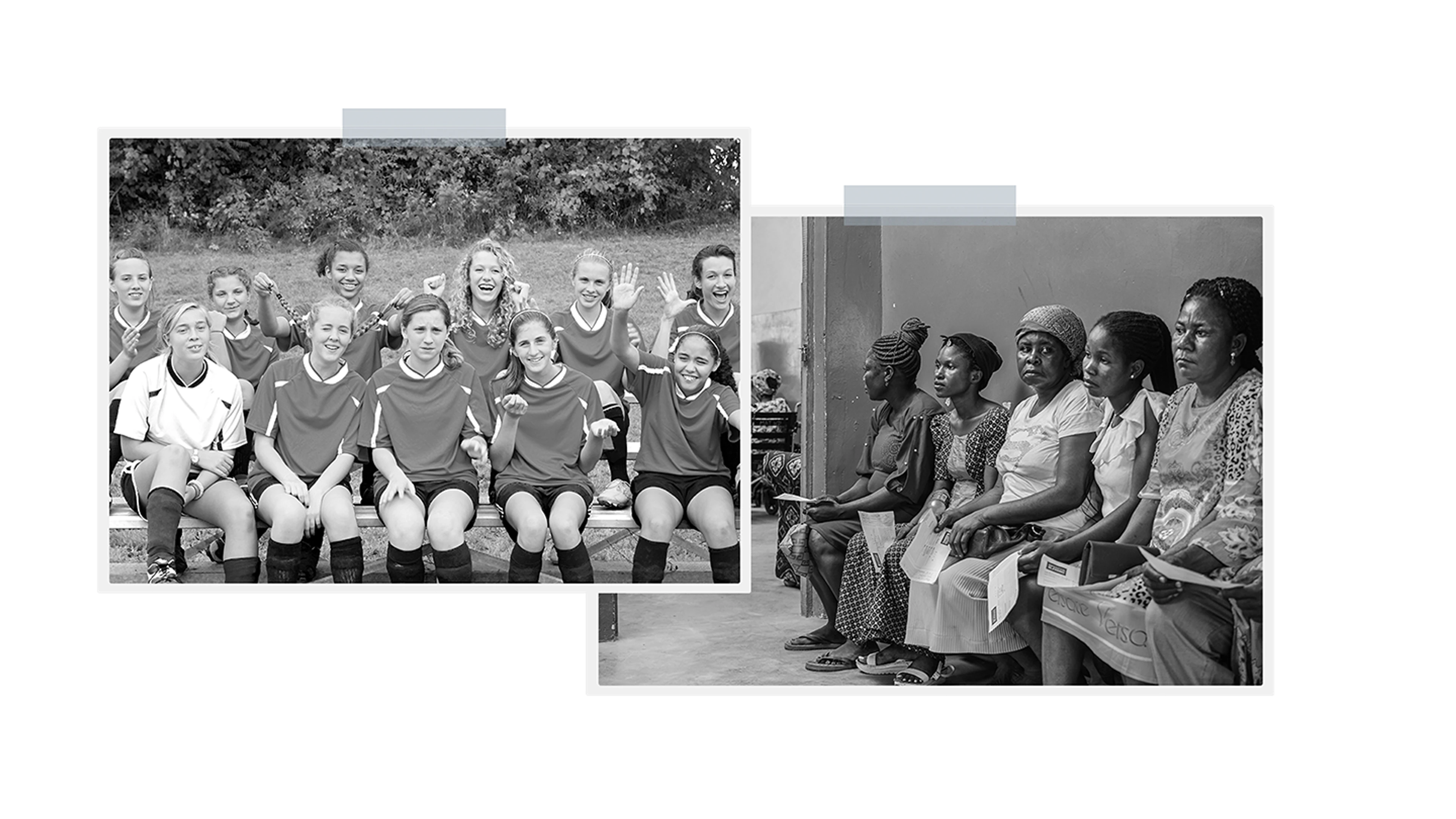

Because it’s one of the most common sexually transmitted diseases in the world, as many as 80 percent of all men and women will have had at least one bout of infection with the Human Papillomavirus by the time they reach the age of 45. Luckily for the vast majority of them, their immune system will clear the virus on its own and there will be nothing more to worry about. For around 10 percent of people with HPV infections, however, the news will be a lot worse, with a diagnosis of cancer that could in many cases prove fatal. The World Health Organization estimates that globally, 620,000 new cancer cases in women and 70,000 new cancer cases in men were caused by HPV in 2019.

Polyomaviruses such as BK Virus and JC Virus are extremely common—almost ubiquitous—in children across the world, most of whom won’t suffer any serious symptoms. But the most common victims of cancer caused by infection with these viruses are people whose immune systems are compromised or weakened, either because of a medical condition or due to ageing. This means elderly people are at greater risk, as well as people who have had kidney or stem cell transplants, people living with HIV, pregnant women and people with diabetes.

Common Harms

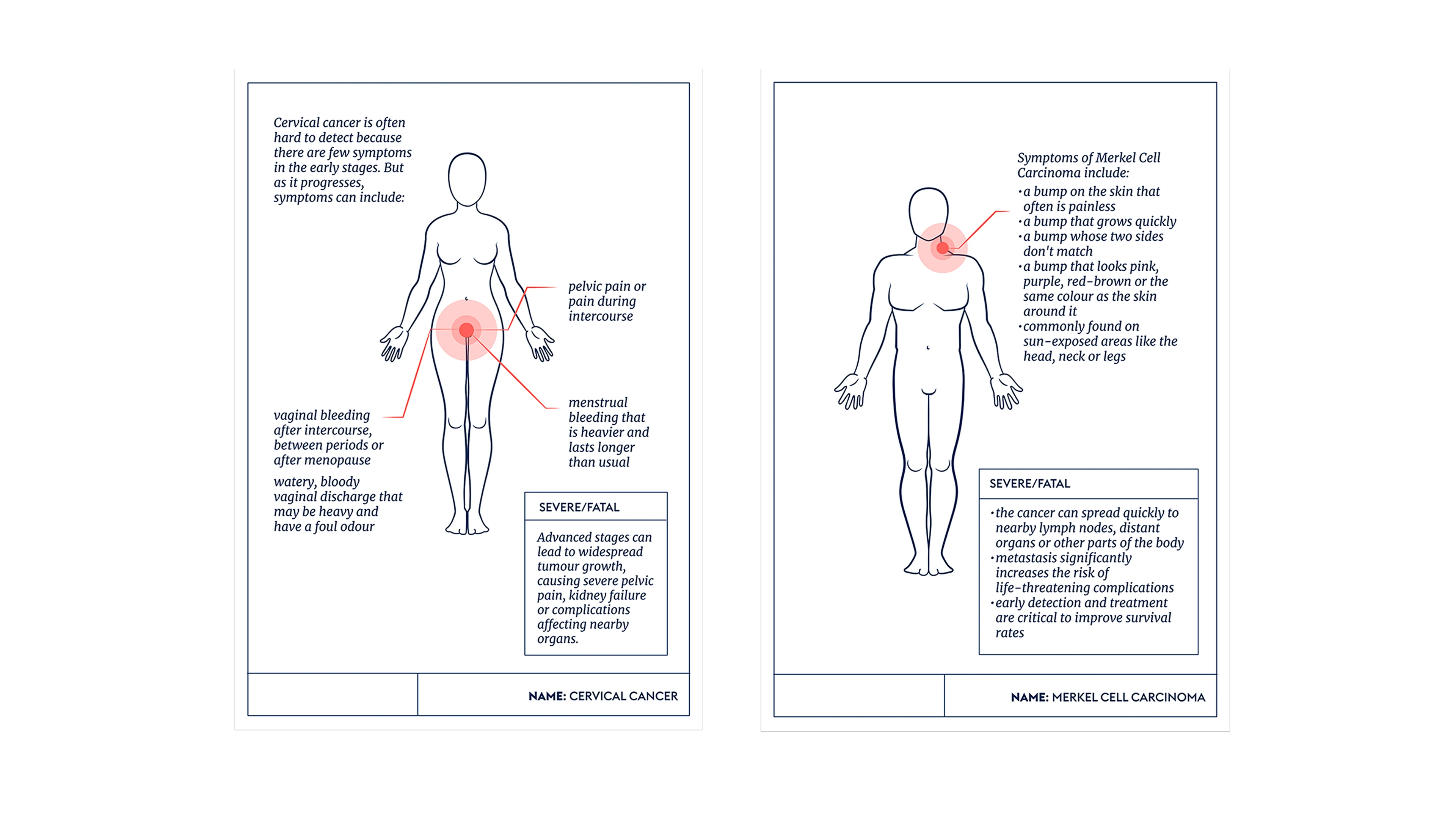

Several types of Human Papillomaviruses—in particular HPV-16 and HPV-18—can cause cancer of the cervix. The main symptoms of cervical cancer can vary and are often very hard to spot, but some common ones are abnormal vaginal bleeding, heavier and longer menstrual bleeding than usual, vaginal discharge and pelvic pain or pain during sex.

Severe diseases and cancers caused by the Polyomaviruses JC Virus, BK Virus and Merkel Cell Virus are relatively uncommon, but they can be serious and aggressive when they do occur. Merkel Cell Carcinoma, for example, is a rare but aggressive type of skin cancer that produces small firm lumps on exposed areas of skin. The lumps, which can be flesh-coloured, red, blue or purple, tend to grow quickly and can sometimes break open and bleed as the cancer progresses. JC Virus can in rare cases cause a severe brain infection known as progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, or PML, while BK Virus is known to cause kidney damage or disease in people with weakened or compromised immune systems.

Lines of Enquiry

Thanks in part to the Nobel Prize-winning Harald zur Hausen’s determination to pursue his line of enquiry into Human Papillomaviruses as the main cause of cervical cancer, scientists have since developed highly effective vaccines to protect against the most dangerous types of this virus. The first HPV vaccine was developed in the 1990s by researchers in Australia and was effective against four major cancer-causing types of HPV. A later version, introduced in 2014, expanded that coverage to protect against several more cancer-causing HPV types.

The World Health Organization now recommends that HPV vaccines should be given to all girls aged between nine and 14 years, before they become sexually active. In countries where HPV vaccination strategies were implemented in the early 2000s, soon after vaccines became available, the impact has been dramatic. Rates of cervical cancer in in Australia and the United Kingdom, for example, had fallen to below six per 100,000 people in 2021, and are projected to fall below four per 100,000 in the coming decade. But while girls in many wealthy countries are currently being vaccinated against HPV infection, the reality is that millions of girls and women in low- and middle-income countries—which account for the majority of cervical cancer cases—are still at risk because they don’t have access to immunisation. In Africa, for example, HPV vaccines only started to be rolled out around 10 years ago, meaning that many women won’t have had access to the vaccine in time to prevent them being exposed to HPV infection.

Researchers are also pursuing a number of lines of enquiry on how to prevent Polyomavirus infections, with several potential vaccines in the early stages of development. None of these has yet been tested in human clinical trials, but some are showing positive results in pre-clinical animal studies.

Editor's note:

The naming and classification of viruses into various families and sub-families is an ever-evolving and sometimes controversial field of science.

As scientific understanding deepens, viruses currently classified as members of one family may be switched or adopted into another family, or be put into a completely new family of their own.

CEPI’s series on The Viral Most Wanted seeks to reflect the most widespread scientific consensus on viral families and their members, and is cross-referenced with the latest reports by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV).

Related articles

Related articles

The Arenaviruses

The Arenavirus family includes some of the most lethal haemorrhagic fevers known. All its prime suspects can cause life-threatening disease and death

The Flaviviruses

Yellow Fever is now known as one of several deadly viral haemorrhagic fevers currently classified a Flavivirus, one of The Viral Most Wanted.

The Paramyxoviruses

This family contains one of the most contagious human viral diseases, as well as one of the most deadly. Explore The Paramyxoviruses.

Matonaviruses and Togaviruses

Multiple lines of enquiry against Chikungunya virus and its viral relatives are being pursued by scientists around the world, with the hope for a new protective vaccine coming very soon.

The Nairoviruses

The prime suspect in this family is a deadly virus that causes its human victims to bleed profusely.

The Poxviruses

The viral family of one of the most fearsome contagious diseases in human history

The Hantaviruses

Some Hantaviruses focus their attacks on blood vessels in the lungs, causing the blood to leak out and ultimately ‘drowning’ their victims.

The Retroviruses

The most nefarious Retrovirus—HIV—has infected 85 million and killed 40 million people worldwide.

The Filoviruses

“one of the most lethal infections you can think of” - and it's one whose deadly reach is extending ever further

The Orthomyxoviruses

These viral culprits have caused the deadliest pandemics in human history

The Picornaviruses

Large, persistent and deadly outbreaks of a crippling infection caused by one member of this viral family meant that it was once among the most feared diseases in the world

The Phenuiviruses

The most infamous Phenuivirus, Rift Valley fever, poses a significant threat to people and livestock causing serious disease and dangerous outbreaks.