Q+A: How CEPI-funded research is supporting the COVID-19 vaccine rollout

More data is needed to better understand how COVID-19 vaccines work in different populations - like teenagers, previously infected but unvaccinated individuals, people living with HIV, and pregnant women — and to know what size and order of shots works best.

CEPI's Director of Clinical Development, Jakob Cramer, discusses the research CEPI is supporting to inform global COVID-19 vaccination strategies and expand access to vaccines.

CEPI was one of the first organisations to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, announcing its first three COVID-19 vaccine partnerships on 23 January 2020—when there were just 581 confirmed cases worldwide.

Since then, CEPI has gone on to establish one of the world's largest and most diverse COVID-19 vaccine portfolios, investing over $1.5 billion. The CEPI-backed vaccines developed by University of Oxford/AstraZeneca, Moderna, and Novavax have all been approved by the WHO and another such vaccine developed by SK Bioscience vaccines has recently been approved for domestic use in Korea. CEPI is also working with pharmaceutical companies and biotech partners to explore next-generation and variant-proof vaccine designs.

CEPI's response to COVID-19 also includes critical research into COVID-19 vaccine shots being rolled out around the world, in addition to some up-and-coming vaccine candidates.

Following two scientific Calls to find clinical trial partners in January and October 2021, CEPI has pushed forward a series of studies, supported by up to $80m+ in funding, to provide scientists and decision-makers with more in-depth knowledge on how COVID-19 vaccines work. The data will also be used to provide information on optimal vaccine use in some of the most vulnerable populations—including people living with HIV and other immunocompromised people, the elderly, and pregnant women—with the ultimate goal of expanding access to COVID-19 vaccines.

For example, CEPI has funded research assessing the impact of ‘mix-and-match' vaccine regimens (ie, giving different vaccines for primary or booster immunisations) and is exploring the performance of COVID-19 shots in different populations, with a focus on evidence gaps specific in low-income and middle-income countries. Most recently, CEPI announced a new partnership with Aurum Institute and the Human Vaccines Project to look at mixed COVID-19 vaccine schedules in people living with HIV in South Africa.

Other clinical research CEPI has supported is looking at whether reduced booster doses, known as fractional shots, can provide similar levels of immune response compared to standard doses in previously primed (vaccinated or infected) populations.

We spoke to Dr Jakob Cramer, CEPI's Director of Clinical Development, to find out more about the research underway and how early data from some of the CEPI-funded trials is already being used to inform national and global vaccination policies.

The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

COVID-19 vaccines were already being rolled out in some nations around the world when we decided to launch these two calls. Why did we feel the need to work with partners to gather this additional data?

To vaccinate people, you need vaccines. You need enough vaccines, and you need to ship vaccine where these people live.

But you also need evidence on how to use the vaccine best.

Across 2020, vaccines had been developed and trialled in healthy adults — mostly in those that had not been infected and in the West. However, healthy adults are not necessarily the populations at greatest risk for severe disease from COVID-19.

We needed more meaningful data to better understand how a vaccine performs in other, potentially more vulnerable, population groups and then to use this new information to support the groups deciding on vaccine use like WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE), WHO, or National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups (NITAGs), and others.

Can you explain why CEPI wanted to collect such a breadth of clinical data?

We knew from global discussions at the time, for example from WHO SAGE meetings and from COVAX's Clinical Development SWAT Team, that there was a long list of additional data that was needed to best inform how we rolled out COVID-19 vaccines around the world.

For example, we needed more information about the protection levels vaccines offered in different age groups (including younger and older populations) as well as in those who are immunocompromised, those who are pregnant, and those who may have already been infected and have some partial immunity.

We also needed more data on vaccinating individuals with different COVID-19 vaccines. At that time, some COVID-19 vaccine supplies were in short supply and there was a question around whether you could use different COVID-19 vaccines as a second or third dose. There was also the question around whether this ‘mix-and-match' approach—scientifically known as a heterologous boost—could be even better than vaccinating with the same shot as it could broaden the immune response.

MCRI fractional COVID-19 dose trial in Australia, Credit: MCRI

We also wanted to see whether reduced [ie, fractional] COVID-19 vaccine doses—while maintaining a good immune response—could minimise some of the side effects reported following vaccine administration.

So, there were a lot of questions we wanted to address and kept the Calls for Proposals open to hear from partners on what was possible—ie, what research they could do in these areas.

What do the findings of the CEPI-funded research show so far?

Our partners at the Oslo University Hospital and its collaborating Hospitals are investigating the safety and immunogenicity of third and fourth COVID-19 vaccine doses in transplant patients and other populations with immune disorders or under immunosuppressive treatment. Their research found that additional vaccines (compared to just a full two-course vaccination programme) have been generally well tolerated and lead to increased immune responses in some patients, but this varied in different patients. The findings from the different cohorts, for example people living with rheumatoid arthritis (The Lancet) and multiple sclerosis (Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychology), are being published as they become available.

Together with the University of Oxford and the University of Southampton, we have addressed questions around mix-and-match boosting, particularly in younger age groups, which has contributed to global vaccine guidance.

For example, their research has revealed ‘mixed' schedules involving Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca produced high levels of antibodies when administered four weeks apart. A follow-up study showed that Moderna and Novavax vaccines could also be used as second dose options after a first dose of Oxford-AstraZeneca or Pfizer-BioNTech. The research also found a reduced Pfizer/BioNTech dose resulted in fewer temporary side effects while still generating a robust immune response.

Additional findings and papers, from projects in low-income and middle-income countries, are expected to be published in later weeks and months.

Participant receiving MCRI COVID-19 fractional dose trial information in Indonesia, Credit: MCRI

Did the changing dynamics of the pandemic influence which clinical research project CEPI decided to invest in?

Yes. We started this programme of work to rapidly address that list of additional COVID-19 vaccine data needs.

As the pandemic went on, the world changed. We faced additional challenges, including great parts of the population in Africa still being unvaccinated, but now getting infected so they were no longer ‘immune naïve'.

This understanding of potentially already having partial immunity led to trial protocols being created by our partners to specifically look at vaccine use strategies for previously infected populations.

Enabling equitable access to vaccines is the key goal in these studies. Could you tell us about this?

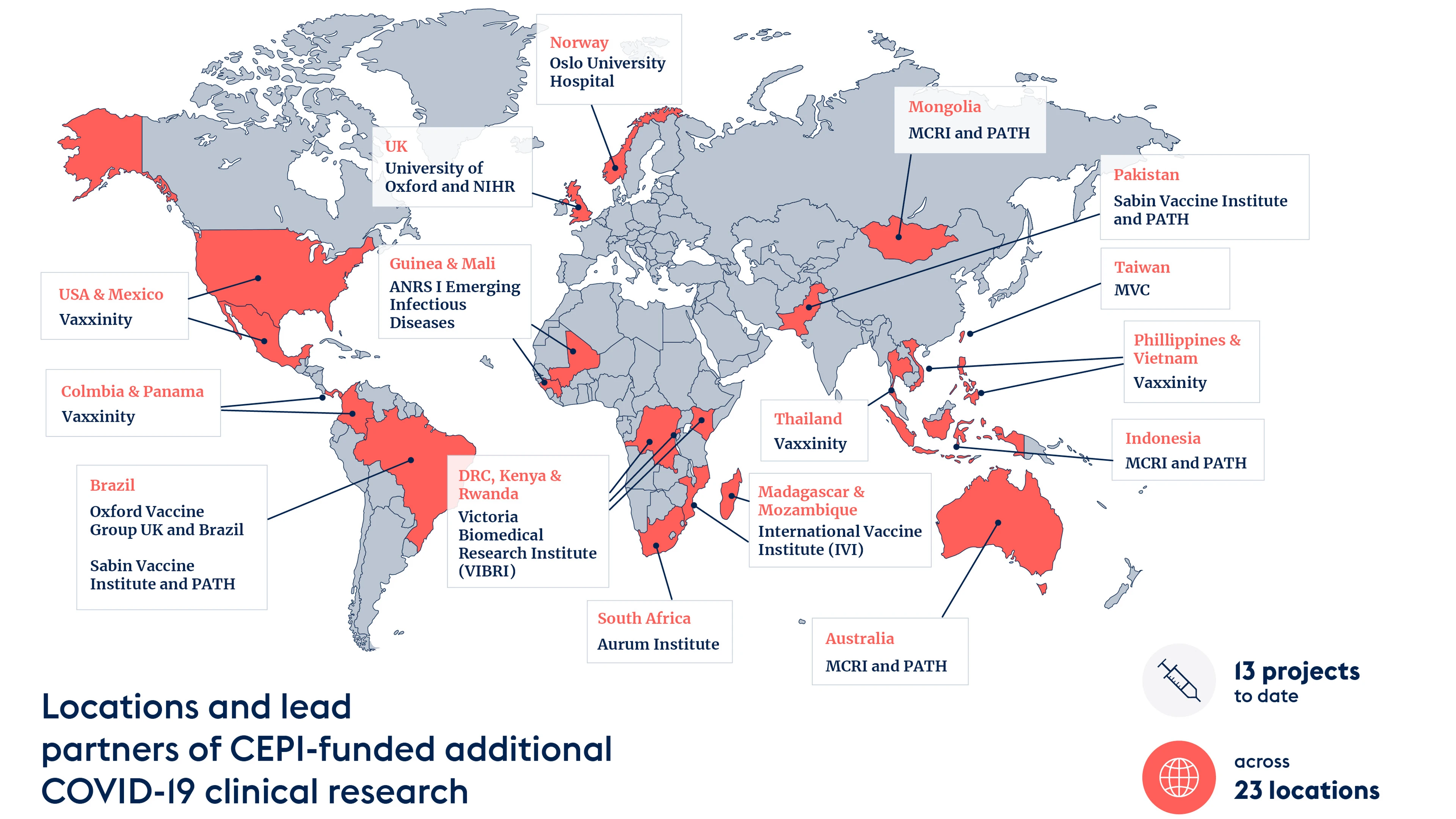

We were very keen to support studies in low-income and middle-income countries as that's where we could work with local populations to get greater vaccine data and, in turn, ensure what was generated was applicable to these population groups. Having set this as a goal, we now have projects running in Mozambique, South Africa, Kenya, Rwanda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Guinea, Pakistan, Brazil, Indonesia, and Mongolia (in addition to some research taking place in higher-income economies, like Australia, the UK, and Norway).

Credit: CEPI

The other part of the access equation is to ensure quick and easy availability of the trial findings. We intend for our partners to make their evidence available through open access platforms as quickly as possible. In particular, we are and will be working with our partners to feed their data into global health bodies guiding COVID-19 vaccination policies, like WHO SAGE Committee and groups within COVAX.

This evidence is needed rather urgently, so we cannot really wait until studies have closed. We would like to see interim analyses as soon as possible.

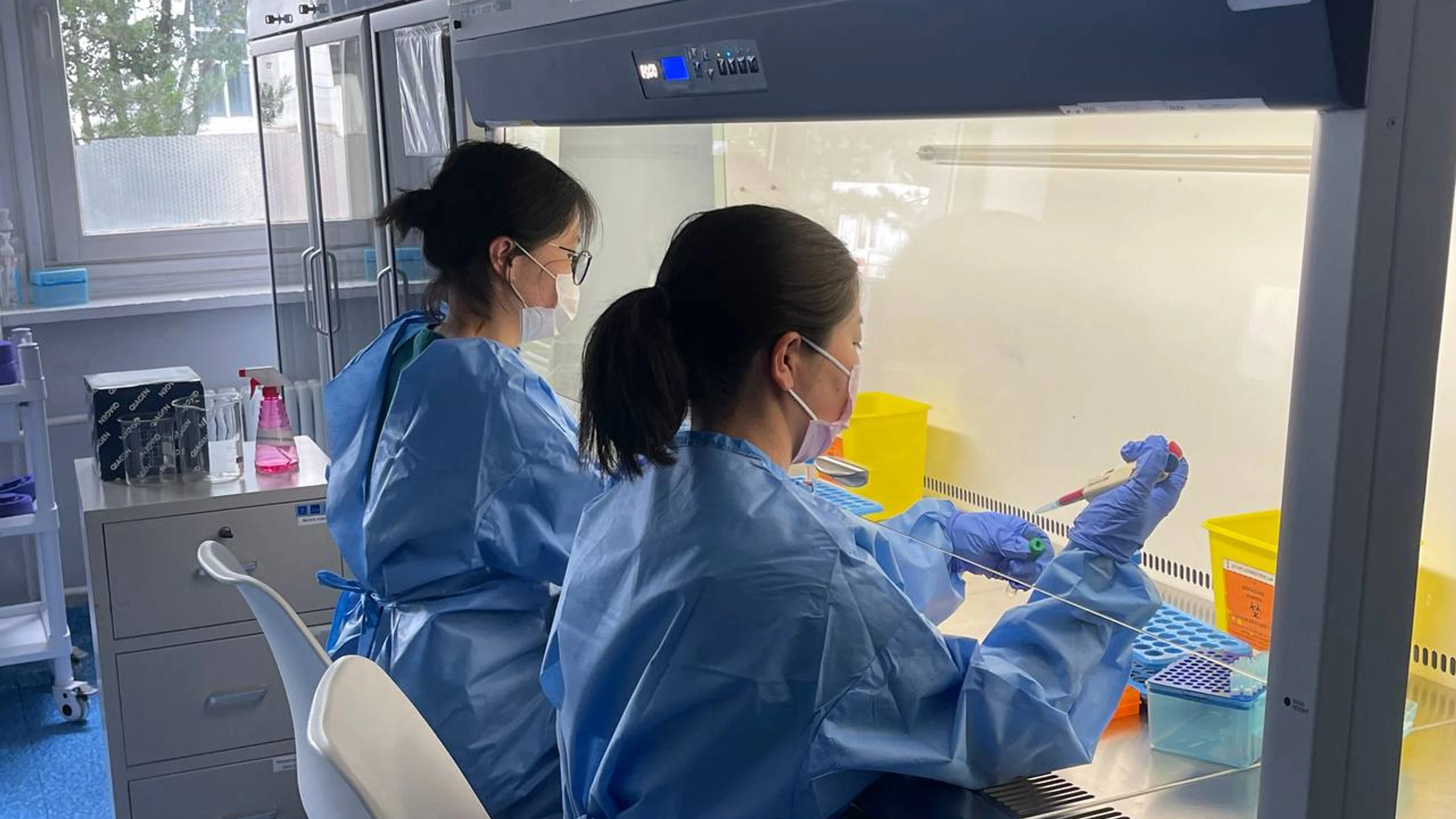

The First Central Hospital of Mongolia processing samples from the MCRI COVID-19 fractional dose trial, Credit: MCRI

These trials have taken place during a fast-moving, fast-evolving pandemic. Did you and our partners face any challenges when collecting data? Are there any lessons learned that should be remembered to help prepare for future pandemics?

We received a lot of very valuable proposals from well-known research organisations in response to our first Call. However, what was challenging is that some of them didn't initially have immediate access to vaccines to begin the trials. This meant there were some delays—at a time when we, of course, needed to be moving incredibly quickly. When it came round to launching the second Call, looking for research specifically for fractional doses, we asked that partners already had vaccine supplies in place, ahead of the trials, to ensure we could move rapidly.

Given the number of projects we supported, we found it valuable to bring on board a third party with the capacity, expertise, and experience of working in low-resource and rural settings to help us review applications and coordinate the implementation of partnership agreements. For example, we've been working with organisations like PATH and IVI as third partners to really advance our work in this field. This is a great lesson learned for future projects.

We have also started to connect all individual projects and sites we have supported under these two calls to support, share, and learn from each other, and are now using our centralised labs network—a global initiative created by CEPI—to be able to compare the robust immune response data generated from these projects.

Beyond that, our COVID-19 clinical trial research is a great case study for us to prepare for CEPI 2.0. We now know how we can work with experienced trial sites and partners around the globe to quickly initiate clinical research and rapidly respond to future outbreaks. This will be incredibly important to understand and practice as we work towards our 100 Days Mission to dramatically reduce the time it takes to produce lifesaving vaccines against future deadly threats.