In late 1997, the World Health Organization and Kenyan Ministry of Health received reports of a number of unexplained deaths in North-Eastern Kenya and southern Somalia. 170 people had died. Many had presented with fever and severe haemorrhaging. The mystery continued as farmers and local veterinarians also reported a concurrent wave of deaths among their livestock.

In as little as three months, this disease had spread across five countries infecting a total of 90,000 and killing around 500 people. The economic consequences of this outbreak were severe—in East Africa, over $250 million in economic damage was caused. Kenyan livestock owners reported losses of about 70% of their sheep and goats and 20—30% of their cattle and camels.

Laboratory testing later confirmed the disease outbreak was caused by Rift Valley fever—an arbovirus that affects both animals and humans.

Rift Valley fever was first identified in 1931 during an investigation into an epidemic among sheep on a farm in the Rift Valley of Kenya. Today, Rift Valley fever is found across Africa and in parts of the Arabian Peninsula.

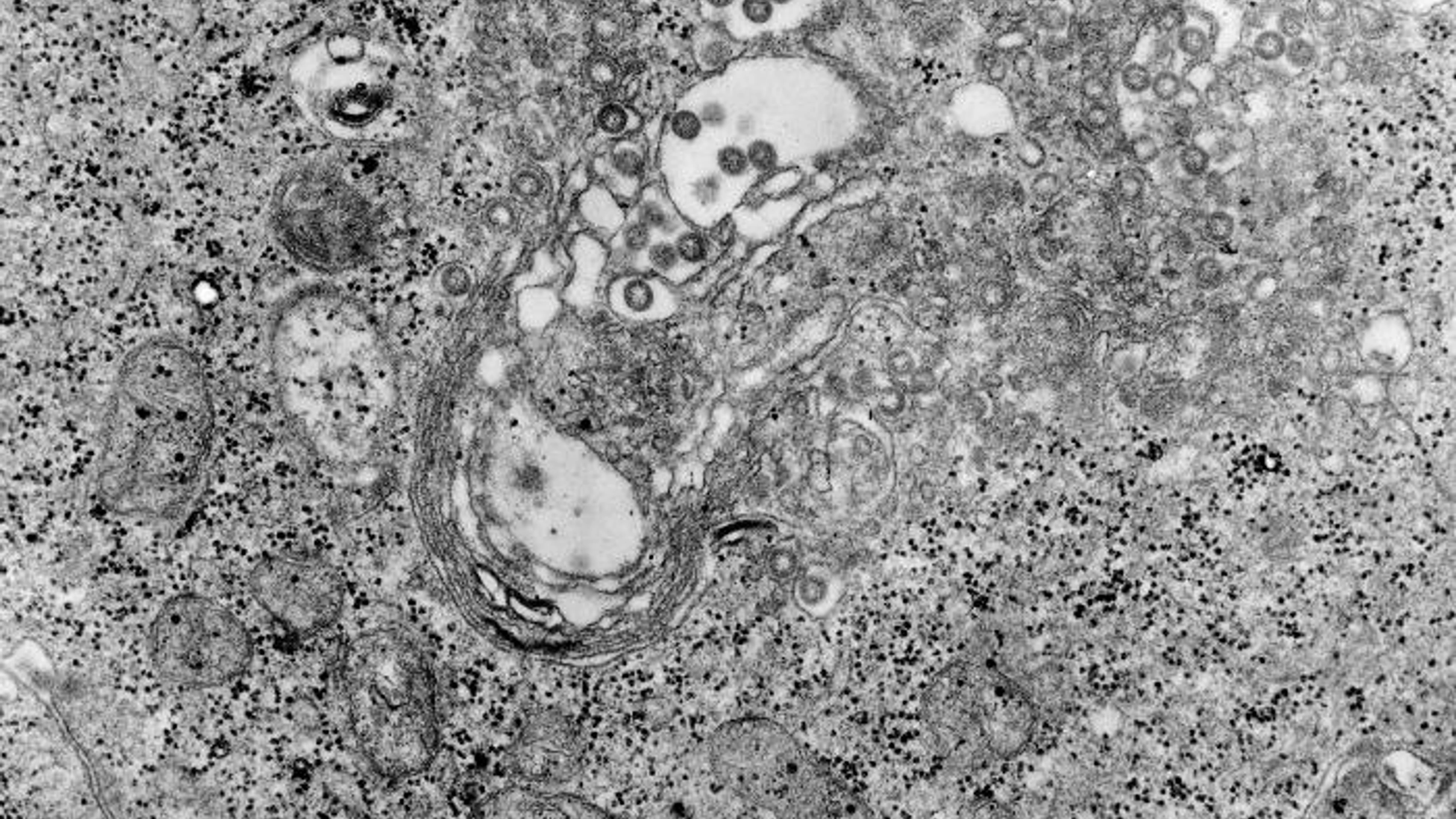

The virus—a member of the Phlebovirus genus—is transmitted by mosquitoes and blood-feeding flies that usually affects animals (commonly cattle and sheep) but can also affect people. Most human infections result from contact with the blood or organs of infected animals but can also result from the bites of infected mosquitoes.

The epidemic potential of Rift Valley fever

Rift Valley fever has the potential to become an epidemic disease, and because of the substantial public health threat posed by Rift Valley fever, the WHO has classified it as a priority disease that is in urgent need of R&D investment.

Rift Valley fever kills about 1% of those infected, but for those who develop the haemorrhagic form of the disease the fatality rate is as high as 50%.

There is also a concern that the virus could be transmitted from human-to-human by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which can be found globally.

Between May and June, 2018, concurrent cases of Rift Valley fever were reported in farmers in South Africa and Kenya, nearly 5000 km apart. There is also an ongoing outbreak on the island of Mayotte, a French overseas territory in the Indian Ocean. As of May 3, 2019, 129 human and 109 animal cases of RVF have been confirmed on the island.

Accelerating development of a Rift Valley fever vaccine

CEPI's mission is to accelerate the development of vaccines against emerging infectious diseases, like Rift Valley fever, and enable equitable access to these vaccines for vulnerable people during outbreaks.

In the case of Rift Valley fever, the people who are most at risk of infection are some of the most vulnerable people in the world. The virus is endemic throughout Africa, and outbreaks usually occur in pastoral communities in lower income countries. These rural communities have reduced access to public health service and their livelihoods are often closely linked to their livestock, which also happen to be the main reservoir for the Rift Valley fever virus.

There is an urgent need to develop a vaccine for humans to mitigate this emerging epidemic threat, protect these vulnerable communities, and strengthen global health security in the process.

In response, CEPI has partnered with a consortium, led by Wageningen Bioveterinary Research, to accelerate the development of a Rift Valley fever vaccine candidate (RVFV-4s) for use in humans.

CEPI, with support from the European Union's Horizon 2020 programme, will provide up to US$12.5 million for a preclinical and phase 1 study to assess the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of a single-dose vaccine candidate against Rift Valley fever virus.

Epidemic preparedness is vital

Dr Mike Ryan, WHO's Assistant Director for Emergencies, said recently that a range of factors such as population movement, conflict, and poor governance were coming together to create a perfect storm for disease outbreaks, stressing that "preparedness has to be a major goal for the world - responding to these events one after another is not a solution."

Rift Valley fever has all the hallmarks of an emerging epidemic threat and if we fail to act now there is a risk that we could see more frequent and deadly Rift Valley fever outbreaks, with serious public health and socioeconomic consequences.

.webp)