Closing in on protection against deadly Nipah virus

Nipah virus is among the world’s deadliest pathogens, yet no approved countermeasures currently exist. CEPI is working to change that through its $150 million Nipah virus R&D portfolio spanning the full preparedness chain—from countermeasure development and manufacturing to anticipating a Nipah-like Disease X from the same paramyxovirus family—including funding the world’s most advanced Nipah vaccine candidate, now in Phase II trials in Bangladesh.

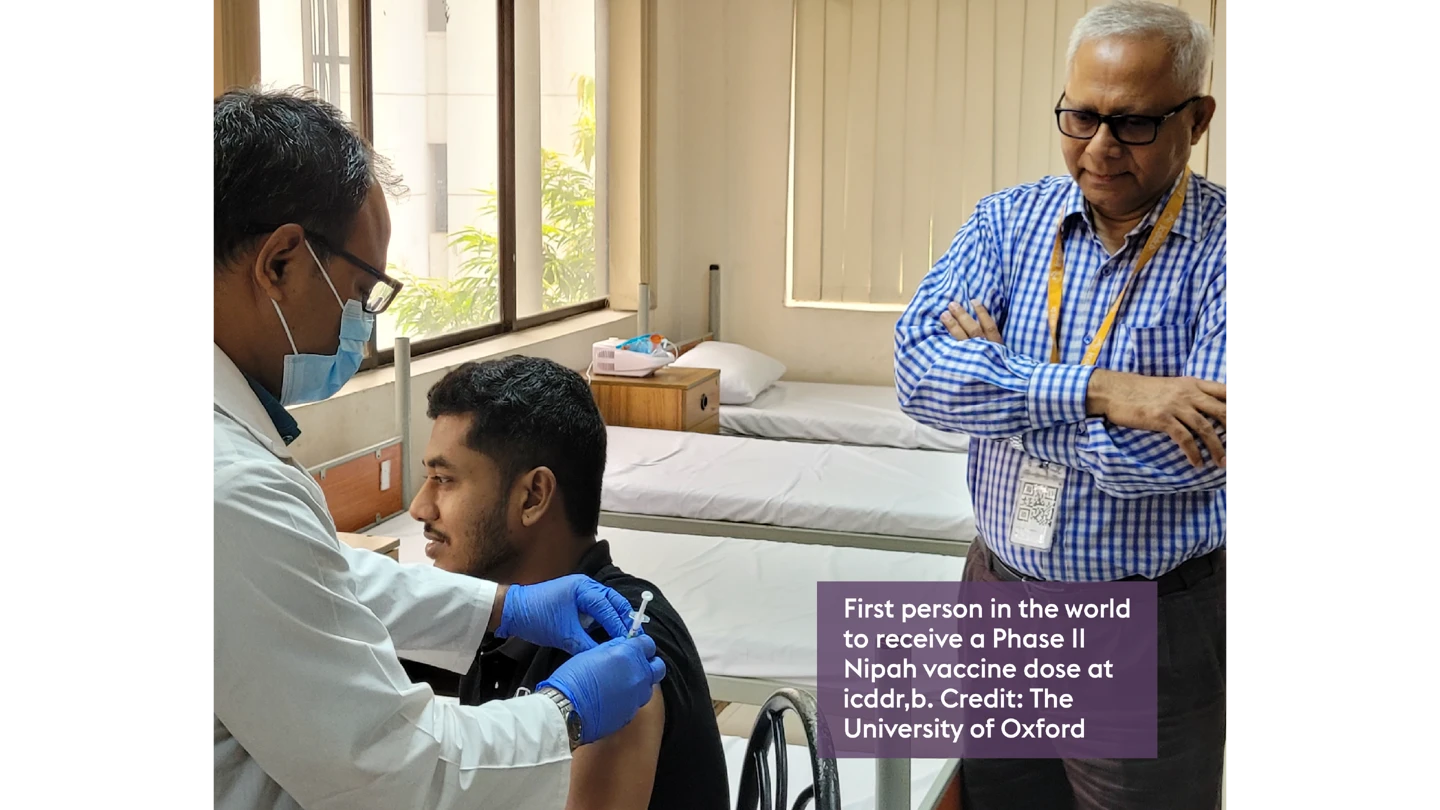

For this Innovations for Impact story, we spoke with icddr,b’s Dr K Zaman, who is leading the first-ever Phase II Nipah vaccine trials, and CEPI’s Nipah programme lead, Rick Jarman, to explore how CEPI is helping the world prepare to confront one of the most lethal viral threats.

___________

Fruit juice—seemingly harmless and enjoyed the world over. But for some people in Bangladesh, drinking a popular local juice can come with deadly consequences.

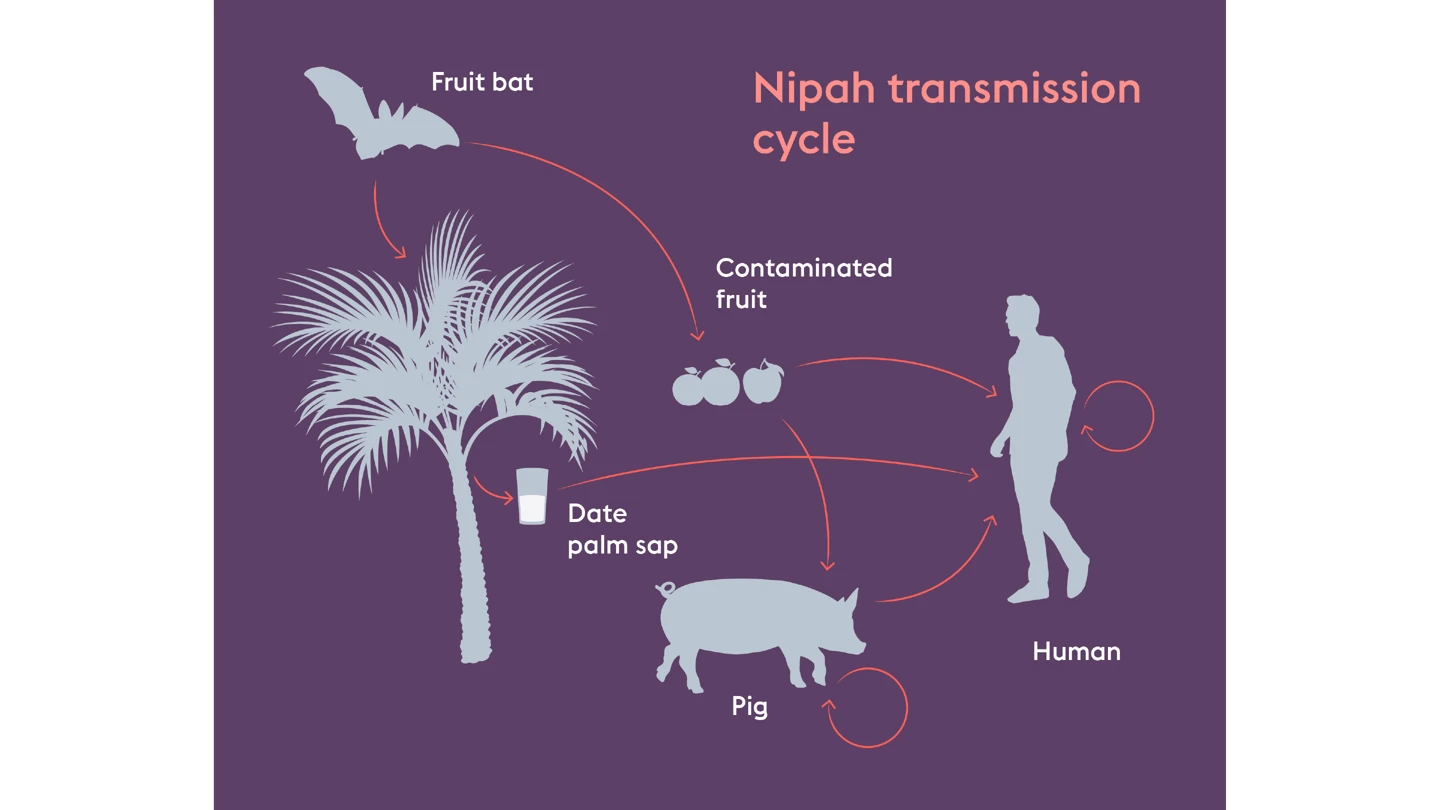

“Raw date juice is a well-enjoyed drink among rural communities in Bangladesh. But many don’t realise it can be contaminated by bats who carry the Nipah virus,” said Dr K Zaman, Principal Investigator of the first-ever Phase II CEPI-funded Nipah vaccine trial at Bangladesh’s icddr,b, a health research institution. “People drink the juice and become infected.”

This simple thirst-quenching accident can prove fatal. Nipah virus kills up to 75 percent of the people it infects. It is one of the world’s most lethal viral pathogens.

It’s this extremely high death rate, and the fact that Nipah has the potential to mutate and spread to many more parts of the world, that is driving scientists to develop a protective vaccine.

One potential vaccine, developed in a CEPI-funded partnership with the University of Oxford and its ChAdOx vaccine platform, was the first in the world to begin mid-stage clinical trials in Bangladesh in late 2025.

Dr Zaman, who has overseen 78 clinical trials at icddr,b, said he hopes this trial will generate new knowledge on how a future Nipah vaccine could save lives in Bangladesh.

And it’s not just Bangladesh that could one day benefit from this vaccine. Since its discovery in 1998, Nipah outbreaks have been confined to South and Southeast Asia. But the virus’s natural hosts—fruit bats—range across regions that are home to more than two billion people. As human activity pushes deeper into bat habitats, the risk of spillover is only growing.

Rick Jarman, Nipah programme lead at CEPI, said the fact that such a large range of domestic and farm animals are susceptible to Nipah virus from bats is a major concern, as Nipah can infect humans both through contaminated food and direct contact with infected animals. Each time it spills over, the risk of mutation and potentially increased transmissibility grows, he said.

CEPI is the world’s largest funder of Nipah research and development. Its $150 million portfolio—including two Nipah vaccine candidates and a monoclonal antibody—spans the whole preparedness chain, from countermeasure development and manufacture, to preparing for a novel Nipah-like Disease X—an as-yet unknown pathogen with outbreak potential—that could emerge from the same paramyxovirus viral family.

A big part of this preparedness comes from CEPI’s partnership with the University of Oxford and Serum Institute of India—the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer and part of CEPI’s Vaccine Manufacturing Network. This collaboration not only enabled Serum to manufacture Oxford’s ChAdOx1 NipahB vaccine candidate for the Phase II Bangladesh trials, but it also aims to create an investigational-ready reserve of up to 100,000 doses of the vaccine. These doses could then be deployed under a research protocol in an outbreak.

Jarman described this investigational reserve as CEPI’s “number one priority” for Nipah virus over the next year or two. With the potential for experimental vaccine doses at the ready in a region where the virus persistently pops up, it becomes possible to launch an emergency trial that can advance the candidate toward licensure and potentially – if the vaccine is indeed effective – provide protection to high-risk individuals.

The collaboration with Serum goes “way beyond being a manufacturing partner”, Jarman said and includes working with a world-class vaccine developer with deep regulatory experience and a strong relationship with the Indian government, alongside the regional experience required to make a Nipah vaccine a reality.

That’s important because large-scale efficacy trials, typically needed before a vaccine can be approved, are unlikely to be feasible given that outbreaks of Nipah are small and sporadic. But the potential data generated if the vaccine is used in emergency settings can help provide an alternative path to approval.

Jarman estimates that a Nipah vaccine could be ready for licensure within the next five years, so building these pathways with regulators now is crucial.

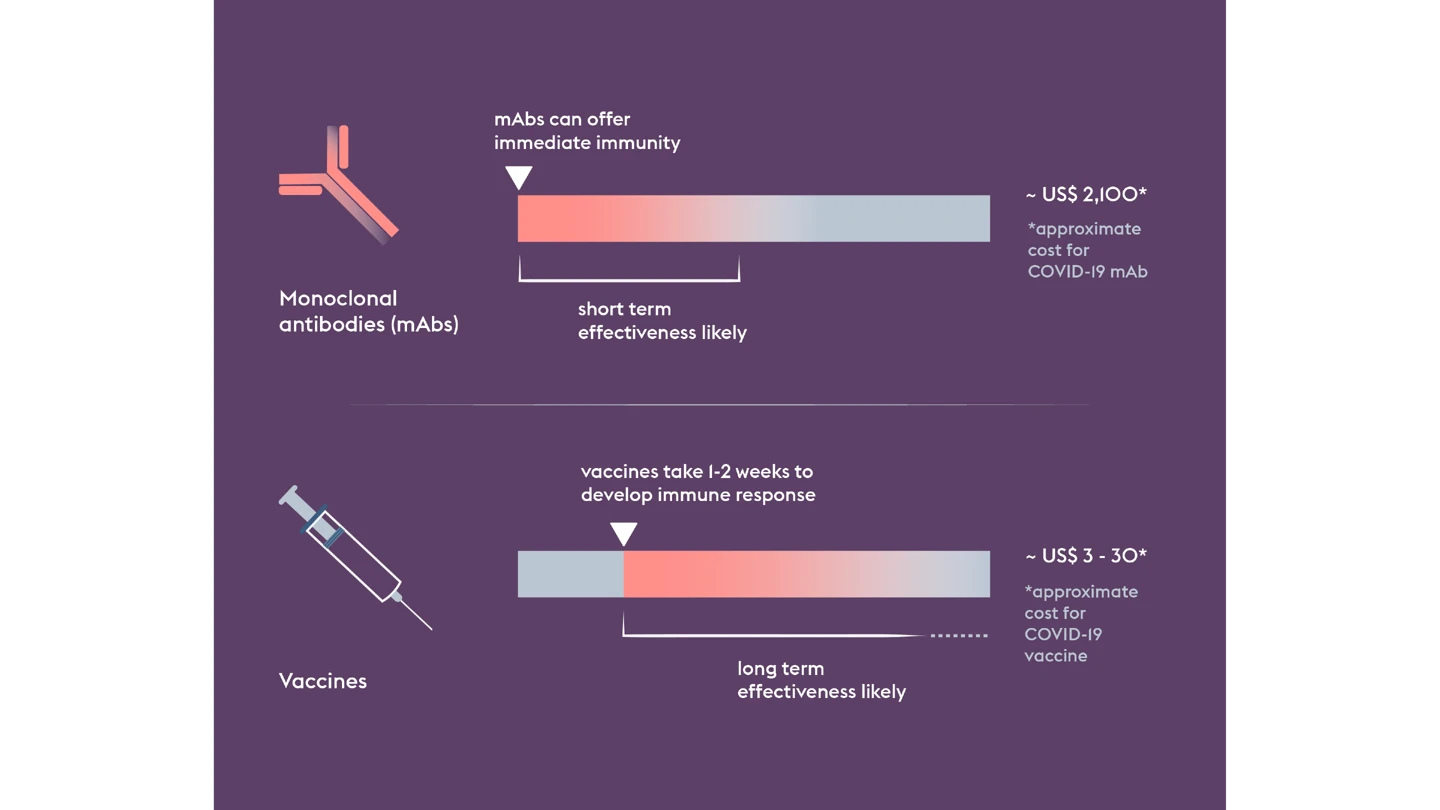

But when it comes to one of the world’s deadliest viruses, vaccines are only part of the story. Even if a vaccine proves successful, it could take weeks before someone vaccinated develops enough protective immunity.

That’s why CEPI is also funding the development of a Nipah monoclonal antibody, or mAb, which could provide immediate protection, acting as a bridge before the onset of longer-lasting vaccine-induced immunity. Such a tool would be particularly useful for protecting high-risk people like healthcare workers.

In what will be another world first, the Nipah mAb, MBP1F5, led by non-profit biotechnology company ServareGMP, is due to begin early to mid-stage trials in a Nipah-affected country in 2026.

Used together—vaccines and mAbs—they could provide a potent protective shield and constrain an outbreak’s potential.

Investing in a range of novel technologies and modalities like this increases the likelihood of successful countermeasure development and helps validate the technology for a future Disease X.

And it helps strengthen global preparedness against not only Nipah virus, but the entire paramyxovirus viral family. If a future paramyxovirus Disease X were to emerge, rapid response platforms like ChAdOx could be quickly adapted to create new vaccines, building on the scientific knowledge and data generated from Nipah R&D. Combined with regional manufacturing capability and expertise, this could accelerate the development of life-saving vaccines against an emerging paramyxovirus with epidemic or pandemic potential. This supports CEPI's 100 Days Mission, which aims to accelerate vaccine timelines to 100 days in response to a pandemic pathogen being identified.

Together, these strands of preparedness—countermeasure development, manufacturing and preparing for a Disease X—form a chain that could one day stop a future Nipah outbreak in its tracks and, at the same time, reduce the threat of other viruses lurking within the pernicious paramyxovirus family.

up to 75%

Nipah virus kills up to 75 percent of the people it infects

Phase II

CEPI-backed vaccine candidate is first-ever in Phase 2 clinical trials

$150 million

CEPI’s $150 million portfolio is the world’s largest Nipah virus R&D fund