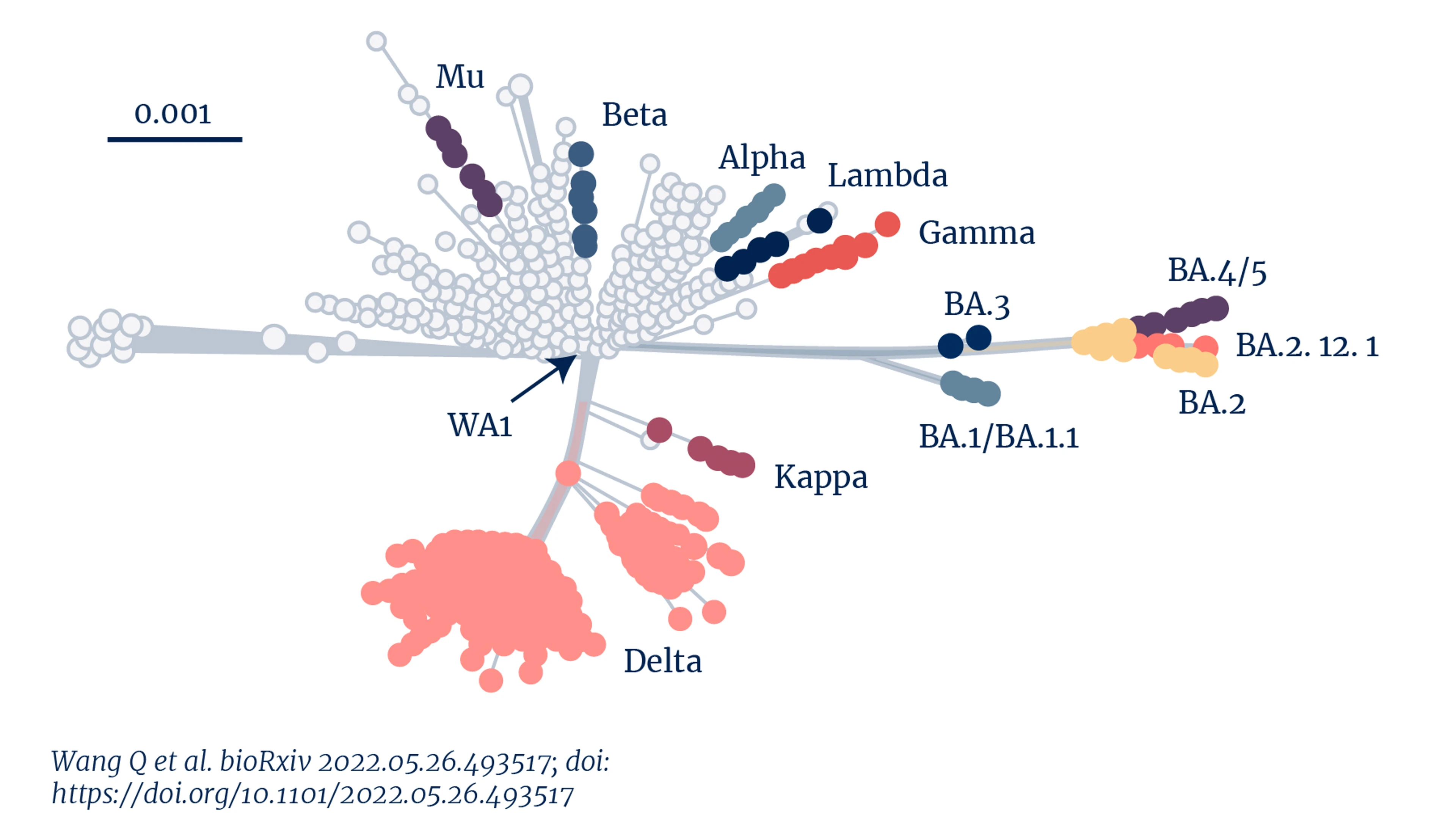

Covid-19 is on the march once again, with an increasing number of infections around the world caused by the Omicron subvariants known as BA.4 and BA.5. What makes these subvariants different from the others that have emerged over the past few years? In these subvariants the Spike protein, the part of the virus that latches on to and enables it to invade cells, has mutated in such a way that it reduces our immune system's ability to identify it and prevent infection.

From a viral perspective that means it is better adapted to evade the immunity of people who have been infected, vaccinated, or both.

Genetic distance of Sars-CoV-2 variants

We're seeing the impact of such adaptation in the recent surge in new infections and re-infections across Europe, UK, and USA, despite high vaccination rates and high rates of previous infection.

This relentless emergence of Sars-CoV-2 variants has shown us it is inefficient at best, and futile at worst, to think that we can make vaccines and treatments against each new variant that arises. Essentially, we cannot keep up with the viral changes in a way that is effective in preventing disease.

This is of concern particularly as the governments around the world are doing battle with understandable levels of ‘pandemic fatigue' within their populations as well as the virus itself. So we need to broaden our scope and our thinking.

The reality is that if the world is to chart a long-term route out of this coronavirus pandemic—and potentially the next coronavirus pandemic—we need to go beyond the ‘one bug, one drug' mindset that has characterised our current response. We need vaccines that can provide broad protection against multiple variants, and even other coronaviruses that harbour pandemic potential.

CEPI foresaw the need for these interventions early on in the COVID-19 pandemic and launched a $200 million programme in March 2021, to advance their development. This programme forms a core part of CEPI's $3.5 billion pandemic plan. Over the past year, CEPI has invested in 11 partnerships to develop these types of vaccines, including two recently announced partnerships with Codiak Biosciences and a consortium led by CPI (Centre for Process Innovation).

Initiating the development of broadly protective coronavirus vaccines should be an integral part of the world's long-term strategy out of this pandemic.

Recent preclinical data, published in Science, showed that it is possible to create a nanoparticle-based vaccine that can protect against both Sars-CoV-1 (the culprit behind the 2003 SARS outbreak) and Sars-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19).

Even better, it is also technically possible to develop vaccines that can elicit responses against all Betacaronviruses, including Sars-CoV-1, Sars-CoV-2, and MERS-CoV—a deadly coronavirus that caused citywide disruption in Seoul, South Korea, in 2015 and has caused multiple outbreaks in the Middle East.

Current COVID-19 vaccines only target one antigen—the Spike protein. And while these monovalent vaccines still provide excellent protection against severe disease and hospitalisation, their effectiveness against mild disease and infection appears to wane against each new variant, and especially against Omicron.

The availability of broadly protective, multivalent vaccines would finally give us an edge against Sars-CoV-2 and the other Betacoronaviruses that we know have pandemic potential. Ideally, these vaccines would elicit both antibody and T-cell immune responses against the Spike protein and so-called conserved "epitopes", parts of a virus that are not subject to constant evolutionary shape-shifting like the Spike protein but which also stimulate the immune system.

Initiating the development of broadly protective coronavirus vaccines should be an integral part of the world's long-term strategy out of this pandemic.

The journey towards these broadly protective vaccines will take time; it will take 2 years or more before clinical trial data gives us a good indication whether they may give broad immunity. Substantial investment will also be needed. But if successful their development will ensure that we're ready for future SARS-CoV-2 mutations before they emerge. Crucially, they would enable us to neutralise the threat posed by other more deadly Betacoronaviruses, like SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV, once and for all.