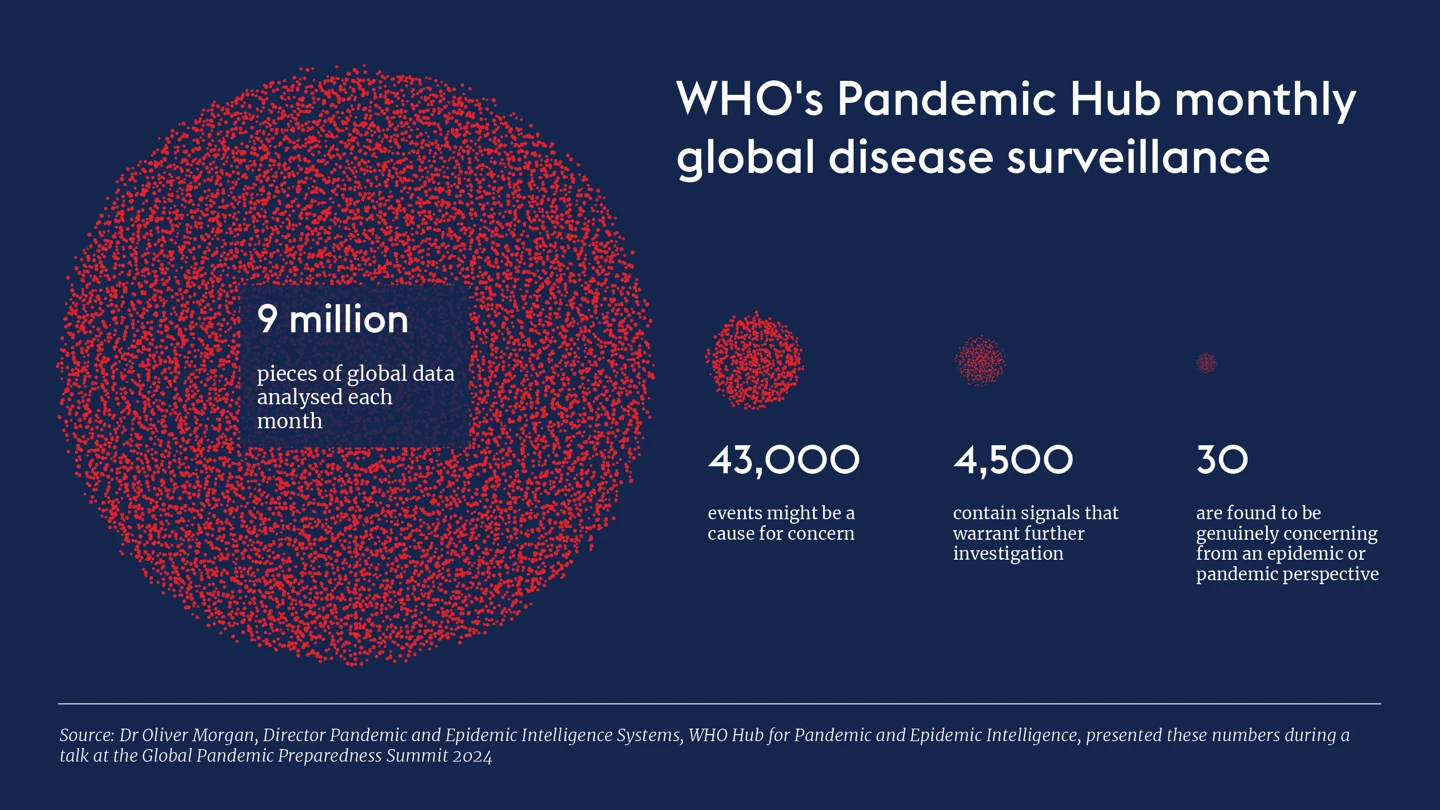

Our first line of defence against emerging viral threats is effective disease surveillance. Global disease surveillance can alert us to the emergence of harmful viral pathogens, track the evolution of pathogens—signalling when they might pose a danger to people—and, crucially, indicate when countries should initiate a response.

We saw this happen during the COVID-19 pandemic, and we’re watching in real-time as outbreaks of H5N1 and mpox in the US and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), respectively, continue to spread—increasing the chance for the viruses to mutate and spread further in human populations.

The problem is that the world’s current disease surveillance infrastructure is not robust nor interconnected enough. Available surveillance infrastructure varies from country to country and this inconsistency creates blind spots at a global level.

“Historically, surveillance has been limited to counting cases and deaths, and a bit of data on morbidity,” says Dr Chikwe Ihekweazu, Assistant Director-General for the Division of Health Emergency Intelligence and Surveillance Systems in the Emergencies Programme, WHO, speaking at the Global Pandemic Preparedness Summit (GPPS) 2024, which took place in Rio de Janeiro on July 29-30.

We want to get to the 100 Days mission. But it’s incredibly difficult to define Day Zero. Every day we're thinking, could this be a Day Zero? Can we start the process that will lead to a vaccine?

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the insufficient nature of our global disease surveillance capabilities, he said, adding that even in areas where it worked well, the data often wasn’t comprehensive enough to hit the go button on developing new countermeasures. These shortfalls make it difficult to know when the so-called “Day Zero” of an outbreak has truly begun.

The concept of a Day Zero is fundamental to the 100 Days Mission—a global goal to develop pandemic-busting countermeasures within just over three months of a threat being identified.

“We want to get to the 100 Days mission. But it’s incredibly difficult to define Day Zero. Every day we're thinking, could this be a Day Zero? Can we start the process that will lead to a vaccine?” says Ihekweazu.

To overcome some of these issues, Ihekweazu highlighted the concept of ‘collaborative surveillance’. This approach emphasises the need for better collaboration across academia, virus and genomic experts, public health institutions, and other sectors to improve the evidence base for rapid decision-making. He explained that such collaboration should establish national and global standards on how to collect data, how to share it, where to share it, and with whom.

Part of this also includes increasing access to available data and integrating data on genomics, hospitalisation, population movement, population density, and AI-derived insights, alongside data that emerge from sources like news and radio channels, with the existing baseline surveillance capabilities.

Linking local, regional, and global initiatives, while combining multi-source, multisectoral data and sharing it collaboratively will help health authorities better understand when a troublesome outbreak may be brewing and help countries respond faster. Ihekweazu explained that this happened in an ad-hoc way during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it’s now time to standardise this approach.

Speaking on an H5N1 influenza panel at GPPS, Dr Marcela Uhart, Director of the Latin America Program at the Karen C. Drayer Wildlife Health Center, also called for the expansion and integration of surveillance data, reinforcing the importance of a One Health perspective. This approach, in part, involves learning from the surveillance of animal viral genomes and using these insights to monitor genetic changes that could signify whether a zoonotic virus might become a more tangible threat to people even sooner.

However, Uhart argued that the pathways to exchanging surveillance data between animals and humans are not yet sufficient.

I monitored [H5N1] for over three months in animals, and it was very different from day one to day 90. Maybe now that it's [adapted to spread in] dairy cows, we’re paying a bit more attention. But we had three years of warning before this happened.

It's clear that the desire for more comprehensive global disease surveillance isn’t some far-flung future need that will only be called upon during the next pandemic threat. The world desperately needs enhanced, connected and collaborative disease surveillance systems now; systems that are always on, always monitoring, and always ready to detect.

A point that Dr Jean Kaseya, Director General of Africa CDC, emphasised at Summit: “If you talk to people working in [surveillance], they are not talking about Disease X. They are talking about the reality that they have today. We need to strengthen disease surveillance in Africa because we have so many outbreaks; we have 160 outbreaks per year – that’s two per month. If we don’t have a strong system that can help us detect and then respond to these outbreaks, we can’t save people's lives.

Fortunately, the capacity to identify outbreaks is constantly improving as global surveillance efforts and the wealth of robust data sources expand.

This increasing recognition and availability of disease surveillance data, coupled with global, regional and local efforts to meet that demand, ultimately allows for earlier detection. This means that Day Zero—the start of the 100-day countdown to develop a vaccine or other countermeasures to halt an outbreak—will become easier to define, case numbers might still be relatively small, and there will be a fighting chance of containing epidemics before they spiral into pandemics.

.webp)