The pain after the bite: Tracking Chikungunya’s debilitating impact in East Africa

Cases of a mosquito-borne virus that causes crippling disabilities are surging worldwide. Experts are working out how many people are affected in Kenya and Tanzania.

In the summer of 2016, Zika virus made headlines around the world. The mosquito-borne illness had swept across Brazil—then hosting the Rio Olympics—and caused global alarm when infections in pregnant women were linked to babies born with microcephaly, a condition stunting brain development, and other neurological symptoms.

Meanwhile, over 6000 miles away in Kenya’s coastal county of Kilifi, newborns were being hospitalised with what looked to be similar syndromes. Prof George Warimwe, a scientific investigator working in the area, got to work exploring whether Zika had reached the region. But the test results came back negative. Whatever was happening in Kilifi wasn’t Zika, so Warimwe and his research team started looking at other possible culprits. Another mosquito-borne virus, Chikungunya, was among the watchlist.

“We set up diagnostic tests against a range of mosquito-borne viruses and started screening stored samples from patients admitted with neurological illness. Chikungunya virus is known to cause neurological disease, so naturally this was among the first pathogens to check for”, Warimwe recalls.

First identified in Tanzania in 1952, the name Chikungunya comes from the Makonde language spoken by a population group in the South-East of the country meaning “to become contorted.” It is an apt description for the debilitating illness that primarily causes fever and severe joint pain that can last for several months or years, making working or even walking unbearable. In some infected children it can cause impaired consciousness and cognitive issues.

Indeed, Warimwe’s hunch was right. Around 1 in 10 children hospitalised in a referral hospital in Kilifi with neurological illness were infected with chikungunya virus. Some were just weeks old suggesting they had contracted the infection in the womb.

This was a startling discovery. While the world battled Zika, Kenya quietly faced its own mosquito-driven crisis.

Chikungunya strikes again

Now, nearly a decade later, Kenya has ramped up its Chikungunya monitoring with improved disease surveillance, testing and mosquito tracking. Because of these efforts, the country has reported over 600 Chikungunya cases this year.

This uptick in illnesses adds to the unprecedented surge of cases being reported worldwide. Nearly half a million infections have been identified since January in known hotspots like Brazil and India, as well as flare-ups in the Indian Ocean islands and locally-acquired cases detected for the first time in China, New York and Paris. Hundreds of travel-related Chikungunya cases have also been reported in several European countries.

In Kenya, most of the Chikungunya infections reported this year have been recorded in Mombasa, a region neighbouring Kilifi.

Although, these case reports are likely the tip of the iceberg.

As Chikungunya symptoms like fever and aching joints mirror that seen in other diseases like malaria and dengue, misdiagnoses are common. Clinicians are also still working out the full spectrum of symptoms - so what’s written in the textbooks does not always match what people experience. The picture is further complicated by the lack of necessary diagnostics.

ACHIEVE-ing more

Launching this week, a new disease detection programme led by Warimwe and funded by CEPI aims to close this knowledge gap and help doctors and scientists understand just how widespread Chikungunya really is in the region.

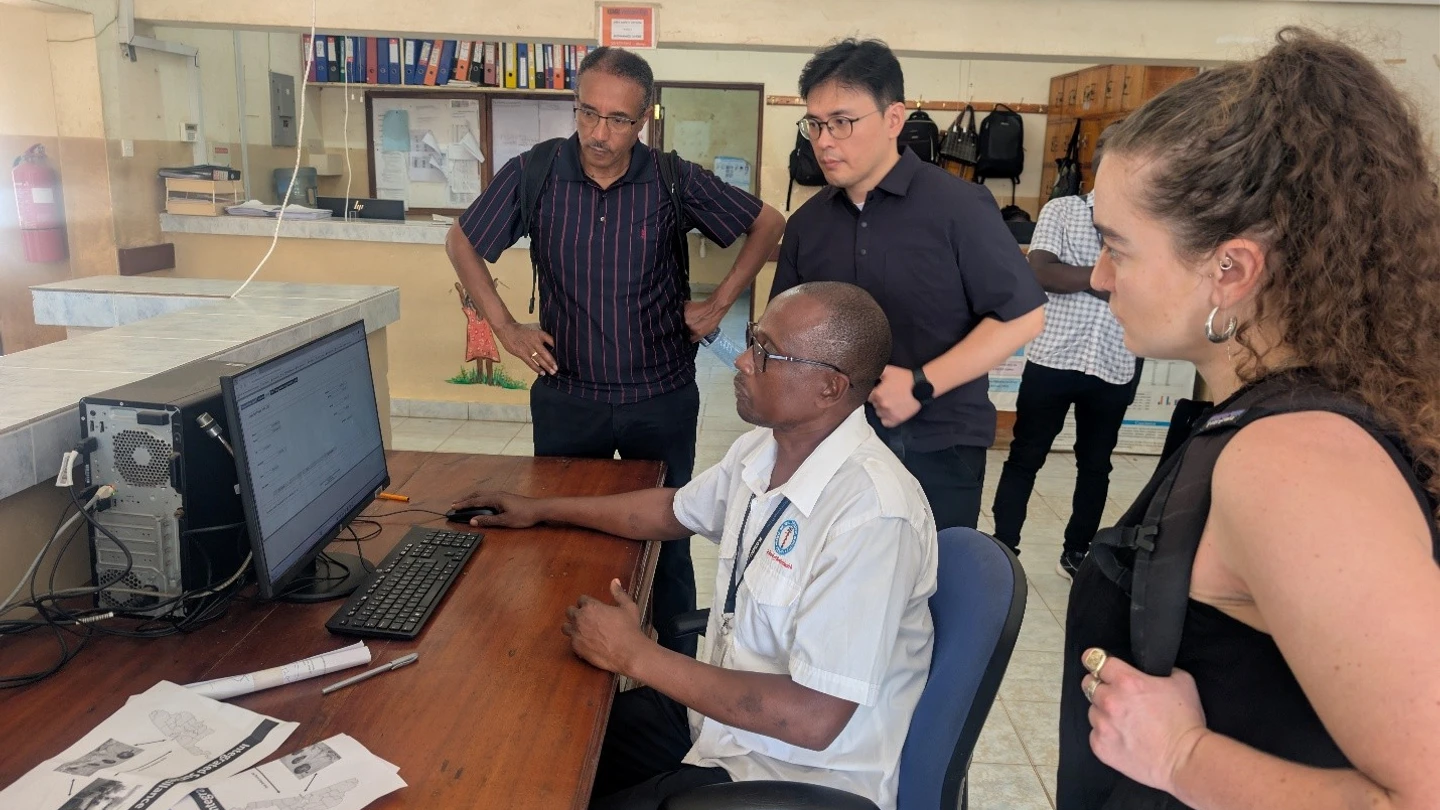

Medical staff at ten hospitals and clinics in bustling towns as well as quiet rural villages across Kenya and Tanzania have been trained to screen every patient presenting with a fever or neurological symptoms that could suggest Chikungunya infection.

“Participation in the study is entirely voluntary, but the study has potential to yield significant public health benefits” says Warimwe.

The aim is to spot illness early, provide care to those affected and track where the virus is spreading.

The study, named Accelerating CHIkungunya burden Estimation to inform Vaccine Evaluation (ACHIEVE), is supported by up to $10.3 million from the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI). In addition to tracking the overall disease burden, it will look at the number of Chikungunya infections in pregnant women and how the virus may pass from mother to baby.

For CEPI, which focuses on vaccine development against infectious diseases, ACHIEVE lays vital groundwork. Knowing who is most affected and where will help design new vaccine trials to gather more data on Chikungunya vaccines. Learnings can also guide decisions on how Chikungunya vaccine doses should be distributed.

“These insights could for example help determine whether children and their mothers should be prioritised – or inform us as to whether we need to also concentrate on other vulnerable groups at risk for this debilitating disease” explains Gabrielle Breugelmans, Director of Epidemiology and Data Science at CEPI. “It’s all about matching protection to the people and places that need it most.”

Researchers will also assess whether different Chikungunya virus strains are circulating in the region, look at the economic impact of Chikungunya on local health systems and communities and measure immune responses in different age groups and over time.

The warming climate

Over a two-year period, ACHIEVE will assess both patients with fever or neurological illness and pregnant women at the time of delivery. This will allow researchers to see how Chikungunya behaves over a prolonged period and whether its spread is affected by seasonal weather changes.

“Warmer, wetter climates create the perfect conditions for infected mosquitoes to expand the areas where they live and breed” warns Breugelmans. “The Chikungunya hotspots of today will not be the same hotspots of tomorrow, so we can’t take our eyes off this moving viral target.”

For now, the ACHIEVE study team are focussed on getting the data to help relieve the pain of this crippling illness.

“Our past work showed chikungunya is especially common in young children,” says Warimwe. “Now, ACHIEVE will assess how widespread the disease is in East Africa and provide the knowledge needed to direct lifesaving countermeasures where they’re needed most”.

The ACHIEVE study team includes scientists at the University of Oxford, University of Nairobi, the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI)-Centre for Global Health Research, the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme and the Ifakara Health Institute in Tanzania.