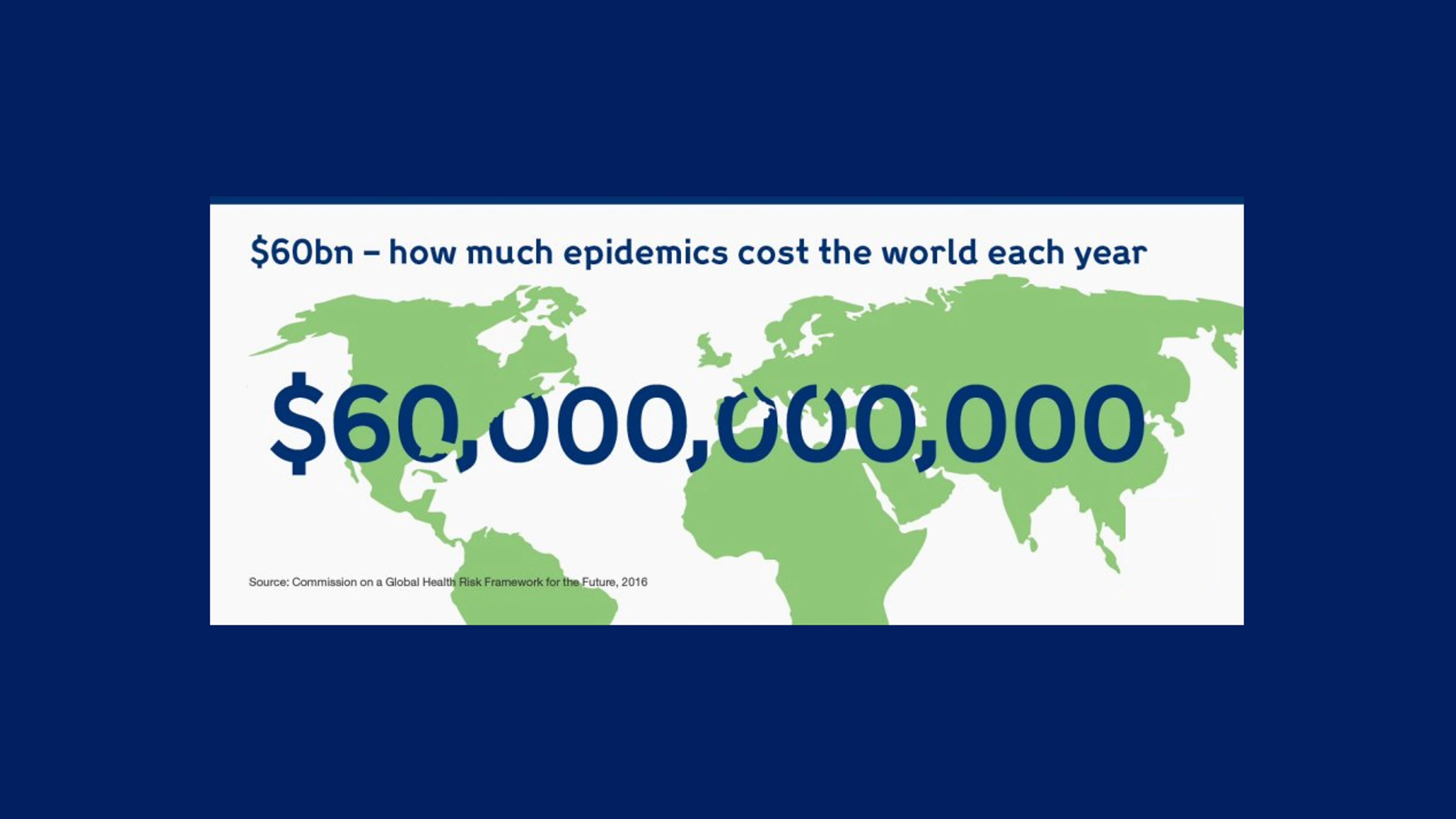

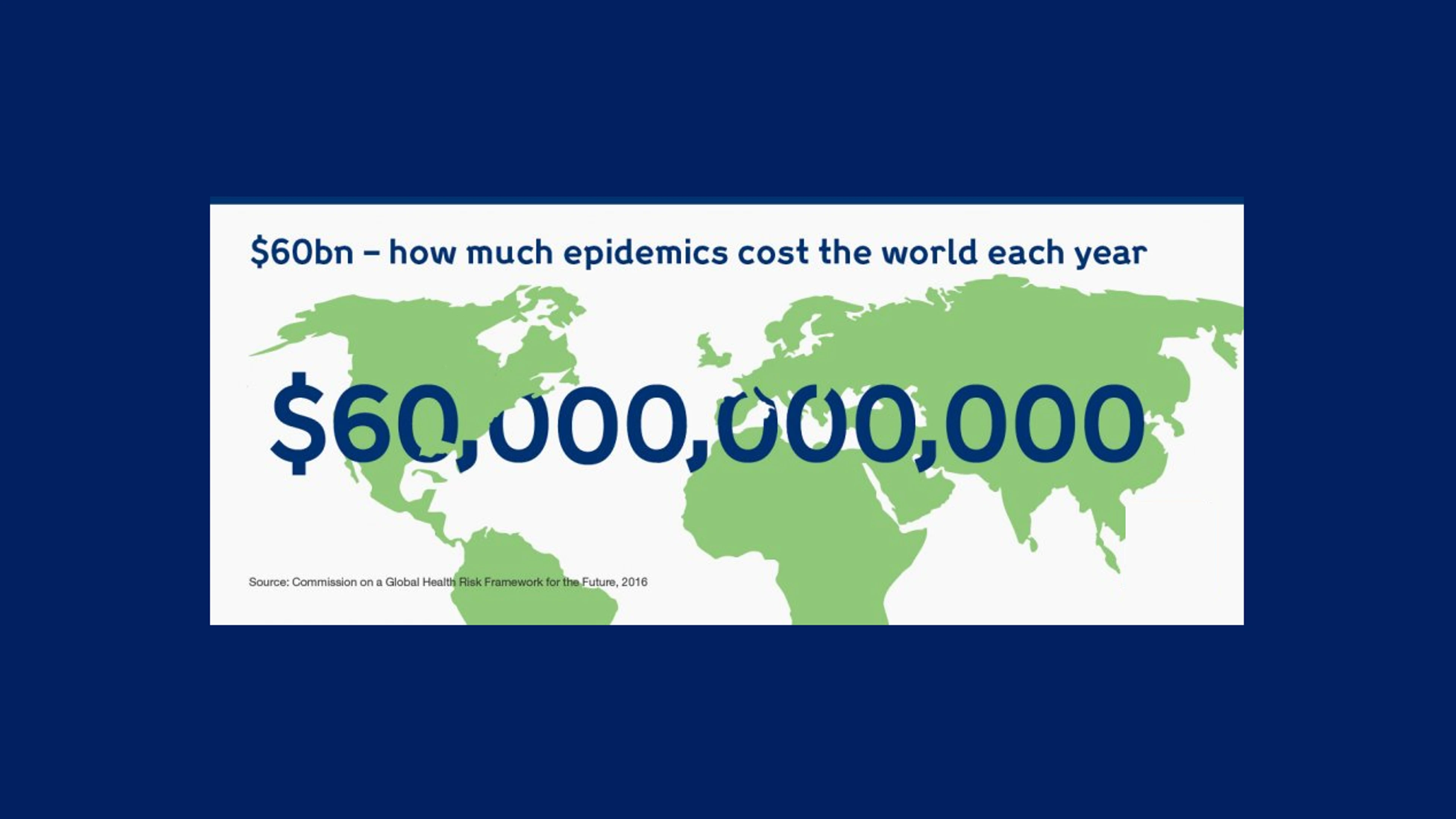

At $60 billion a year, not preparing for epidemics costs far more than putting the systems in place to prevent infectious diseases from spreading around the globe. Here's why.

There are more epidemics than the general public hears about — most don't make the headlines.

This article by Wellcome explores the numbers behind the epidemics and highlights the economic importance of tackling outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases.

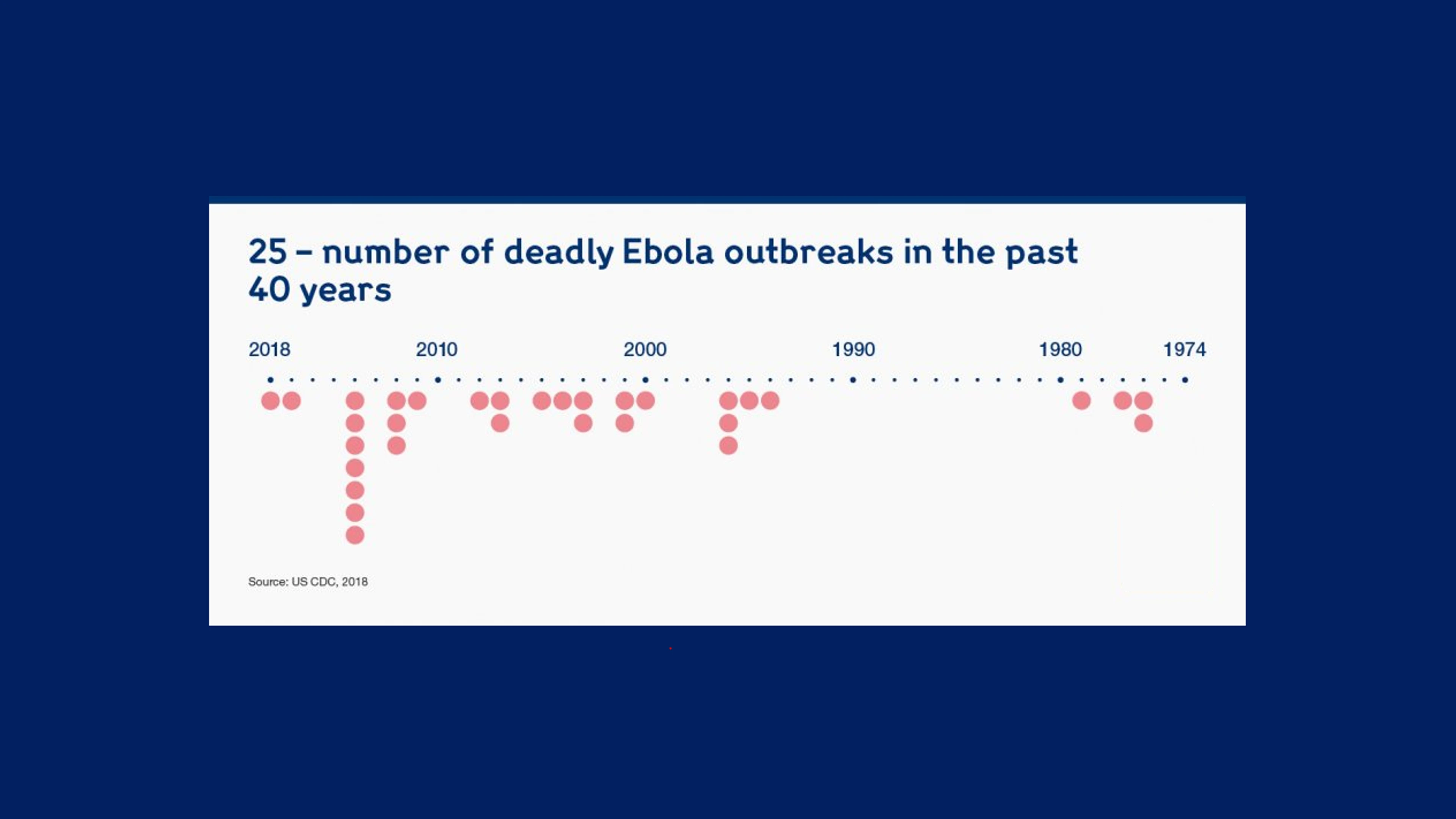

Take Ebola. Since it emerged in 1976, there have been more than two dozen deadly outbreaks.

Number of Ebola outbreaks since the virus was first discovered, Wellcome

That represents just one infectious disease. Between 2011 and 2017, many more epidemics happened — the equivalent to over 186 every year.

.webp)

Number of epidemic events 2011-2017, Wellcome

Epidemics are not cheap — they are costly to fight, and have a big impact on economies.

Cost of epidemics per year, Wellcome

The cost of epidemics is unsustainable. They devastate the world's poorest countries, lessening their ability to develop economically.

Four years ago, when Ebola struck in West Africa, $2.2bn of economic growth was lost in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. When Zika hit the Americas in 2016, the short-term economic impact was $3.5bn. And when SARS spread through Asia in 2003, it had a significant impact on the affected countries' GDPs, with a loss of $40bn.

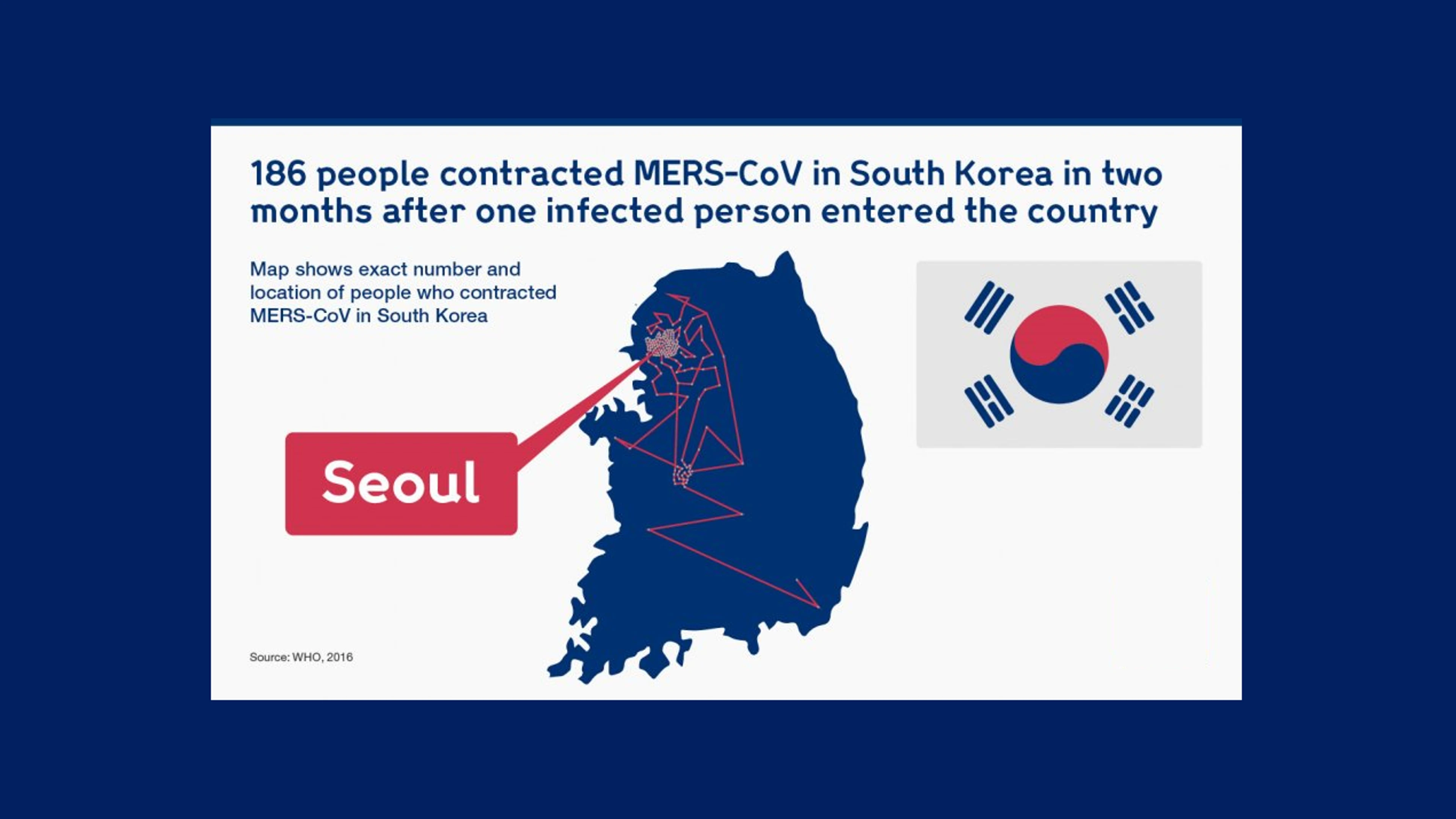

To take another example, MERS, when it infiltrated Seoul from Saudi Arabia in 2015, spread rapidly through South Korea in two months.

People infected with MERS in South Korea in 2015, Wellcome

At $8bn, the expense of stamping out MERS over that period cost more than the country makes each year from exporting computers.

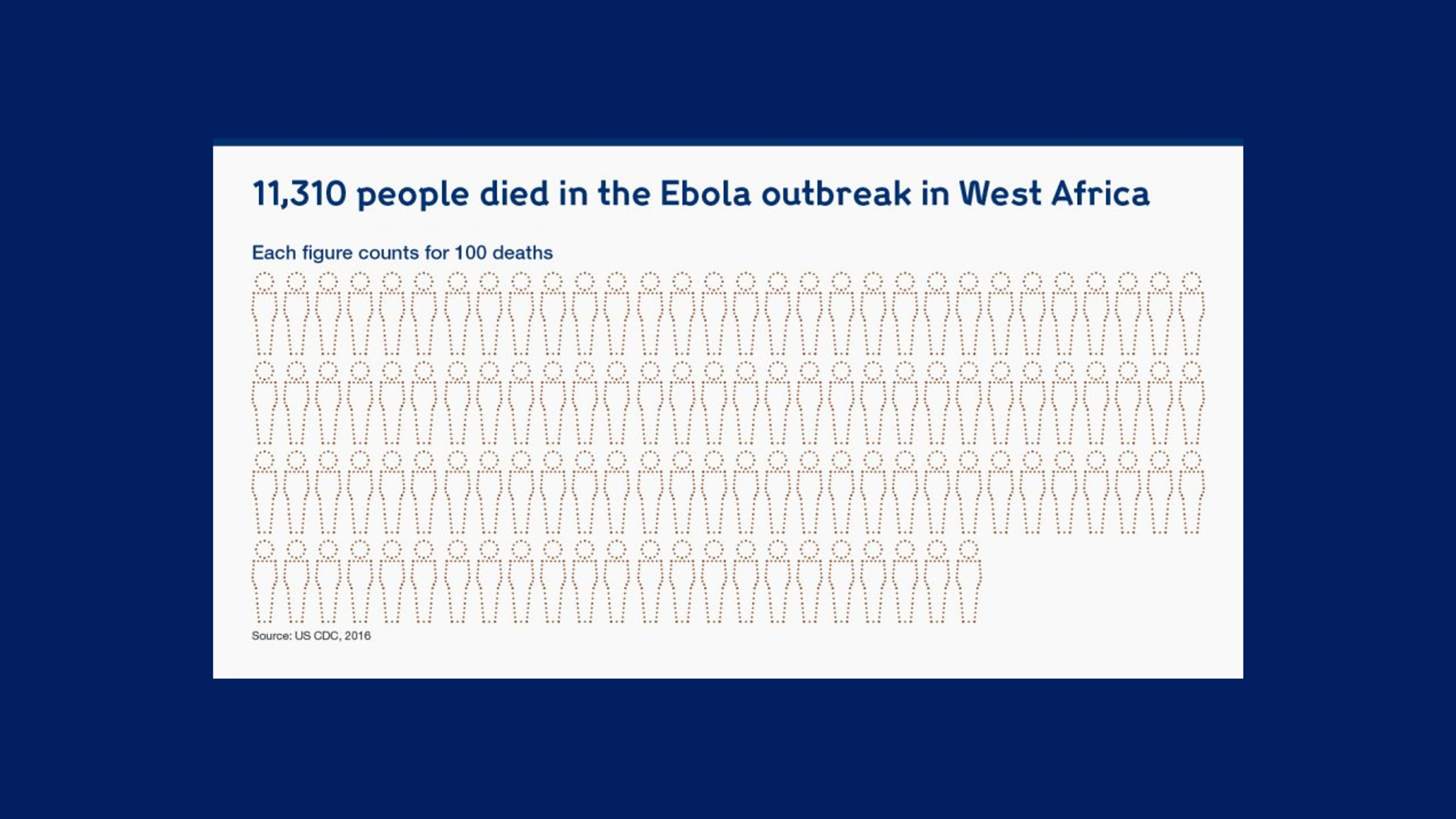

But the economic cost of fighting infectious disease must not obscure what lies squarely in an epidemic's path: people. Whole communities and regions were devastated by the West African Ebola outbreak, with the virus infecting 28,616 people. Nearly half of them died.

Number of people who lost their lives to Ebola in the West Africa outbreak, Wellcome.

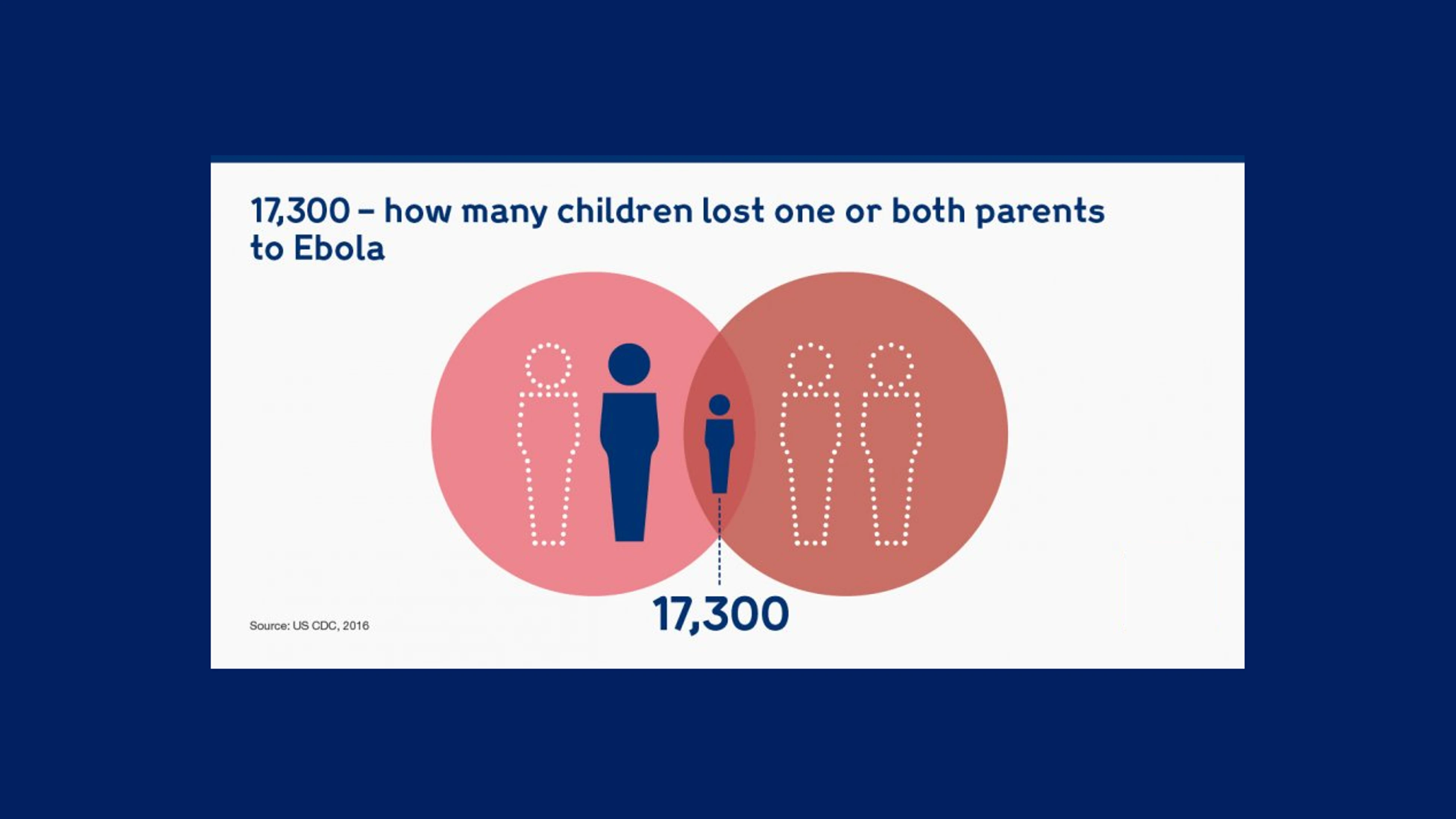

The hardest hit were the most vulnerable people in society: children.

Children who lost parents to Ebola, Wellcome

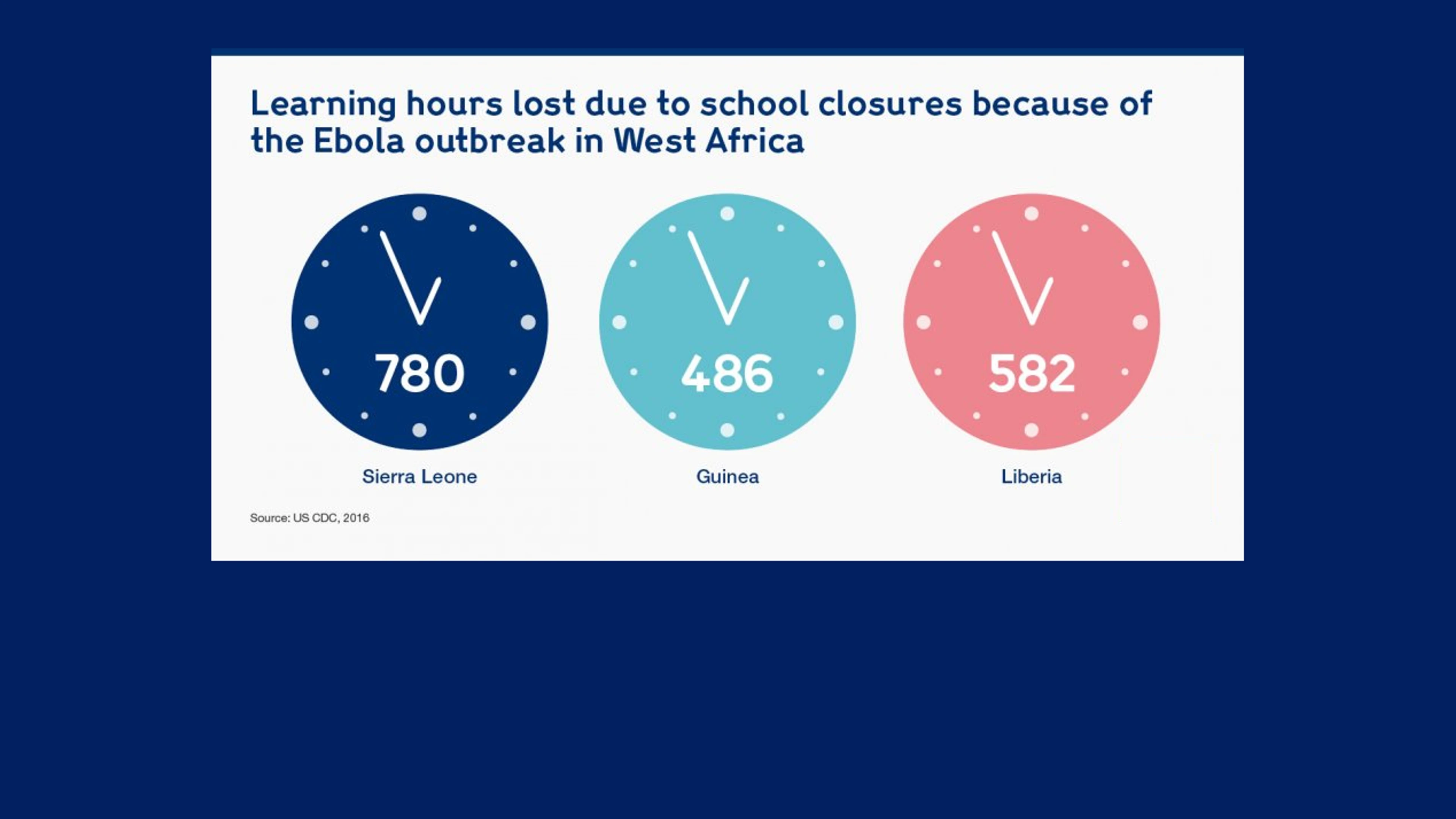

Aside from the impact on their emotional wellbeing, children face another challenge as a result of surviving an epidemic — the impact on their potential for future employment and earnings due to loss of education.

Epidemics also erode health systems, disproportionately affecting those, like children, who rely most on healthcare.

Learning hours lost to due school closures during West Africa Ebola outbreak, Wellcome

But the 2018 outbreaks of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Nipah in Kerala, India, have shown us what we can do if we prepare — we can contain epidemics before they spread through populations and over borders.

Containing these events took a series of overlapping measures: global leadership working side by side with national governments and local health workers, adequate funding for research, and private-sector commitment. Indeed, we're still witnessing how a coordinated response to the current Ebola outbreak in the DRC can overcome the challenges presented by the instability of a conflict zone.

We have a very good idea of the systems we need to put in place to stop these epidemics in their tracks. But we're not there yet. Our safety net has too many holes that need to be mended — we must not be complacent. We need to act now to prevent a global crisis later.

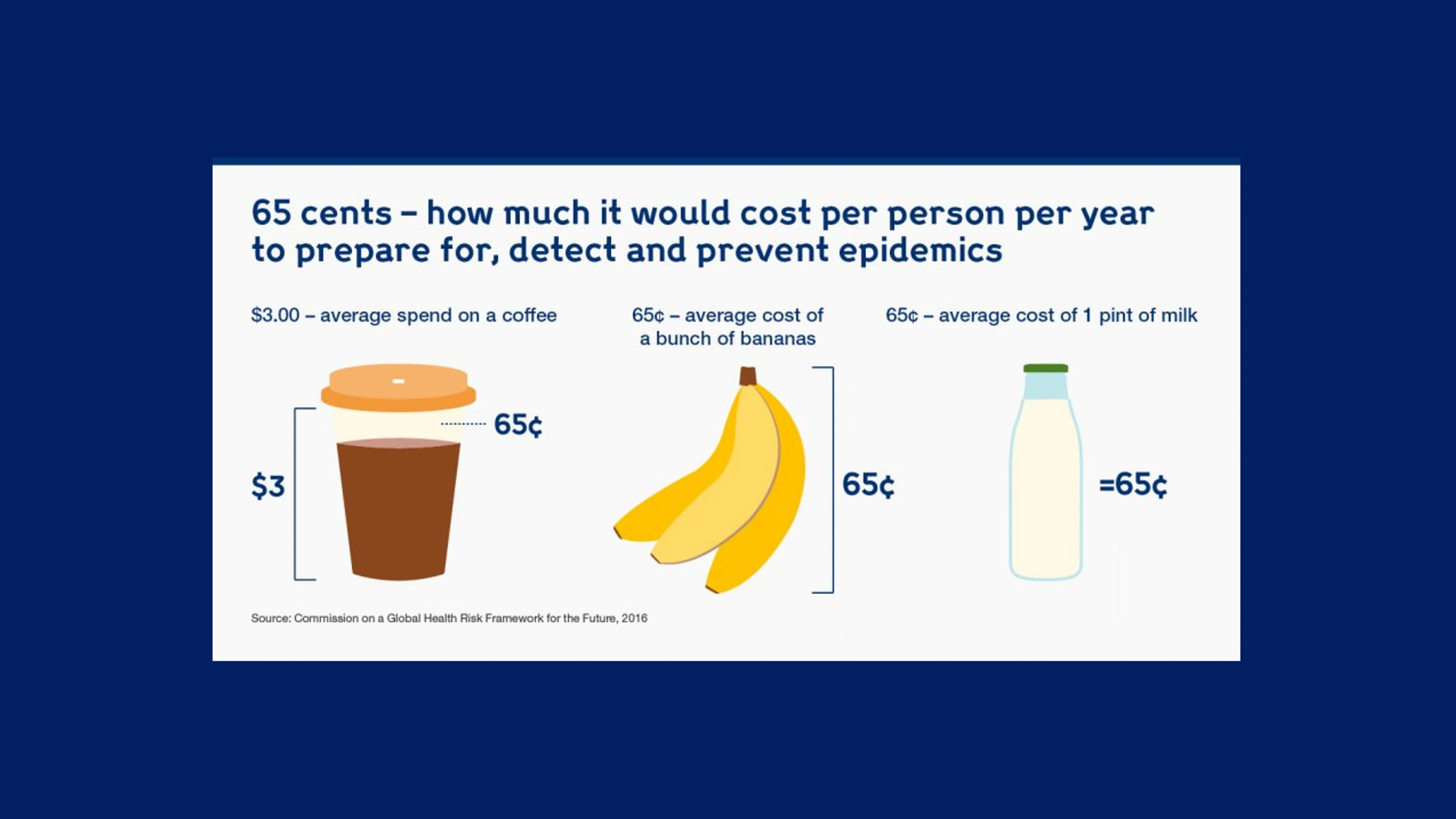

The good news is, at $4.5bn per year, the recommended investment to make us prepared is well within our reach, especially when broken down per person.

Cost of epidemics per person per year to prepare, detect and prevent epidemics, Wellcome

The bulk of that investment, $3.4bn, would be used to upgrade public health infrastructure and capabilities in low- and middle-income countries. Another $1bn would fund research and development for epidemic diseases — and with the WHO R&D Blueprint in place and global alliances such as CEPI leading the development of vaccines, we know where to focus our attention.

With this investment, supported by political will and private-sector involvement, we can prepare today for future epidemics. The human and economic cost of ignoring the problem is too high for us not to.

This article was first published by Wellcome on 19 December 2018. Find out more at https://wellcome.ac.uk/hubs/epidemics.