Rift Valley fever: What's next for the climate-driven disease with epidemic potential?

The current rapid spread of COVID-19, monkeypox, and other potentially deadly pathogens shows just how important it is to invest early in disease research so that we can be better prepared for future infectious disease threats - whenever or wherever they may strike.

One such disease with epidemic potential is Rift Valley fever. Spread by a virus of the same name, this potentially deadly Rift Valley fever causes periodic outbreaks, often driven by climatic changes across Africa and parts of the Arabian Peninsula. Spread by infected mosquito species, it affects both animals (including cattle, sheep, and goats) and humans. As climate change and extreme weather events increase in frequency, there is growing concern that we could face more devastating outbreaks in the future.

Despite first being identified in the 1930s, the disease is vastly under-researched, with no vaccines or other treatments currently available for human use. Given the growing climate change risk, CEPI, earlier this month, announced a new US $50m call, in collaboration with the European Union Horizon Europe programme, to advance the development of vaccines against this worrisome threat into early clinical trials.

We spoke to Mike Whelan, Vaccine R&D Project Leader at CEPI, to find out more about the disease and how CEPI and the European Union are progressing the Rift Valley fever vaccine pipeline forward:

What is Rift Valley fever?

Rift valley fever is a virus mostly found in the Eastern side of Africa, in the Rift Valley, which goes from the top to the bottom of the continent.

It is an RNA virus belonging to the Phenuiviridae genus of the Bunyaviridae viral family. Other viruses in this overarching viral category include Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever, Hantavirus, and Sandfly fever.

Rift Valley fever is transmitted by different species of mosquitoes (Aedes, Culex, Anopheles, and Mansonia) as well as blood feeding flies. It most commonly affects domesticated and livestock animals, such as cattle, sheep, goats, and camels, but can also cause illness in people. Although the disease is mostly mild in humans, it can cause a deadly haemorrhagic fever in 1-2% of cases.

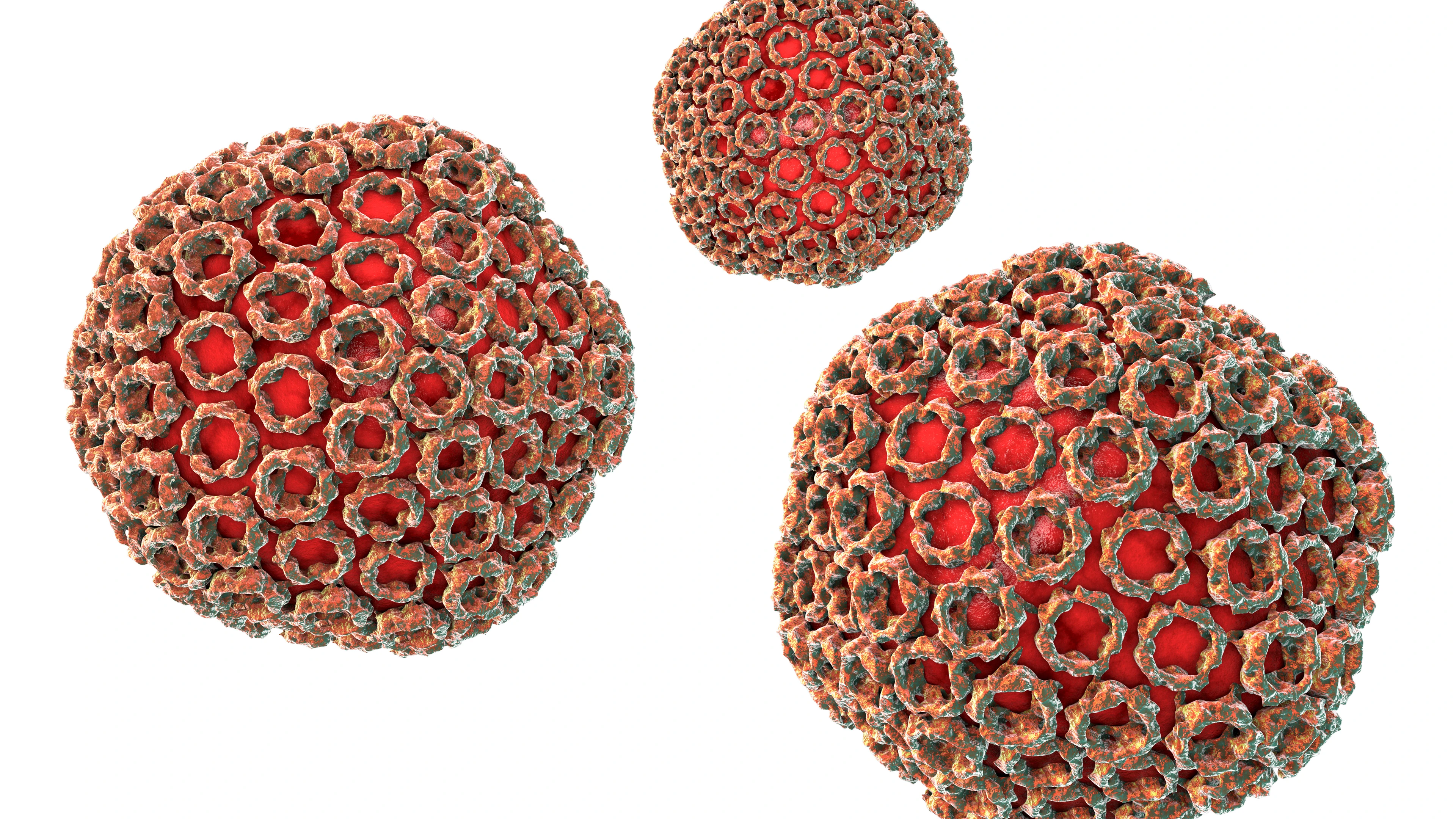

Rift Valley fever virus particles illustration, Credit: Kateryna Kon/science

It was first formally identified in 1931, although reports of a similar illness affecting animals in Kenya's Rift Valley date back to 1912.

In recognition of its epidemic potential, Rift Valley fever is listed alongside the likes of Ebola, MERS, Lassa and Nipah, on the WHO's R+D Blueprint, as well as by the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH).

How is Rift Valley fever spread?

Outbreaks usually start after rainy season, where we get mosquito blooms. The infected mosquitoes then bite animals and the animals bite humans, so we get a spread. At this time, we do not know where the reservoir of disease is, although it is most likely in wild animals.

Since its first identification, outbreaks of Rift Valley fever have typically occurred in 4-15-year cycles and have been consistently linked with periods of surges in rainfall that occur as a result of the El Niño phenomenon. This is a climate pattern that describes the unusual warming of surface waters in the parts of the Pacific Ocean. By changing the distribution of heat and wind across the Pacific, El Niño alters rainfall patterns for months to seasons.

Rainy season in Lira Uganda. Credit: Dennis Wegewijs

As El Niño becomes more frequent and stronger in the future as a result of climate change, the distribution of mosquito breeding grounds could increase with large rainfalls, resulting in the emergence of new risk areas for Rift Valley fever outbreaks.

Where has it spread to?

Rift Valley fever happens pretty regularly in relatively small numbers, in Africa — and cases have also been reported in the Arabian peninsula.

However, occasionally, we get very large and very explosive outbreaks that have very large cases and numbers.

For example, in Kenya in 1997, in as little as three months, a total of 90,000 people became sick and almost 500 died. Kenyan livestock owners also reported losses of approximately 70% of their sheep and goats and 20—30% of their cattle and camels and there were further farming challenges as a number of countries imposed heavy livestock importation bans on the country.

Planet Earth covered with network of air routes based on real data. Elements of this image furnished by NASA. Credit: Anton Balazh

Combined with the later outbreak in 2000, the disease is estimated to have cost the region $300 million, causing collapses in livestock markets which, at the time, made up the majority of national income for countries like Somalia.

As one considers the implications of climate change, it could mean that the disease is going to be found in additional regions in the future.

What are the symptoms typically seen in humans?

In humans, Rift Valley fever is normally a fairly mild disease. It usually causes flu-like symptoms as well as dizziness, liver abnormalities and weight loss. But 1-2% of people become very severely ill and can have a haemorrhagic fever.

There's also blindness associated in up to 10% of those who recover from infection. Sometimes that can be permanent, so it can be a very serious disease.

[embed]http://vimeo.com/759499834[/embed]

Who does Rift Valley fever typically affect?

Rift Valley fever is normally found in individuals who work very closely with animals such as herders, abbatoir workers, and veterinary surgeons.

How does it affect these communities?

Although the case fatality rate (the number of people who lose their lives to Rift Valley fever) is relatively low, there are also other consequences.

Quite often these people are subsistence farmers. In many cases, they will lose their herds and therefore lose their livelihoods. So, actually, if the disease doesn't cause the problem, the consequences, such as risk of poverty and starvation, very much do. It has very many wide-ranging implications and it's something that CEPI needs to support.

Are there any vaccines or treatments currently available?

There are currently no treatments and no vaccines available for it. Although, here at CEPI, we've been working on two vaccine projects, with support from the European Union, which are in early stages.

[embed]http://vimeo.com/758658701[/embed]

One is being developed by Colorado State University in the US and the other from Wageningen in the Netherlands. Both of these are called live attenuated vaccines which are based on versions of the virus which will not give you symptoms. They're attenuated in such a way that the immune response thinks it's seen the virus, but, in fact it hasn't and it's not going to do you any harm, but it will give you protective immunity when you eventually see the real thing.

Currently, these are in early stages, and we only have one Phase I trial— which is the very first safety trial, essentially to make sure everything is okay — and that's being done in Belgium as we speak.

What is this new funding call and why are we launching it?

This new Call, launched with the European Union, will be taking the next step.

We want to look at more advanced clinical development, where we are going to take vaccine candidates which are ready to go into people and we'll do what is called a Phase I and Phase II trial. Phase I being safety, Phase II is: does it work? Does it do anything?

We want to do this in regions where the virus actually is, because, after all, that's what we need moving forward. Applicants must be committed to CEPI's overarching principle of equitable access i.e., any developed Rift Valley fever vaccine must be made first available to populations when and where they are needed, regardless of ability to pay.

Applicants will also be asked to develop plans to scale-up manufacture of their vaccines, and we'd also like to see thinking around future regulatory engagement.

How much funding will be available?

The current call has a value of EUR 50 million, of which EUR 15 million comes from CEPI and the remainder comes from the European Union.

Sudanese farming village, Tannoob, farming livestock, soybean, wheat and corn cultivation. Credit: Sebastian Castelier

And finally, how does this all relate to the topic of One Health?

The One Health Concept is really interesting because it looks at three pillars. It looks at disease in humans, disease in animals, and also includes climate change.

Rift Valley fever is a prime example of this. We tend to only see disease in animals after there has been a climatic event, for example a rainy season or something like that. Next, we see disease in animals which is then transferred to humans.

So, really, the question is: Where do we do the intervention? Do we vaccinate the animals? Do we vaccinate the humans? Do we vaccinate a bit of both? Rift Valley fever will allow us to really look at this.

Importantly, this concept of zoonotic transmission, or a disease which jumps from animals to humans, is very common. If we can find a way to break this cycle this could be important for many current and future disease control strategies.

Find out more about our new Rift Valley fever vaccine funding call here.

Interested in submitting an application? Further details and information on how to apply is available on our website.