For International Day of Women and Girls in Science, we caught up with CEPI Deputy CEO Aurelia Nguyen to discuss her career as a woman in science.

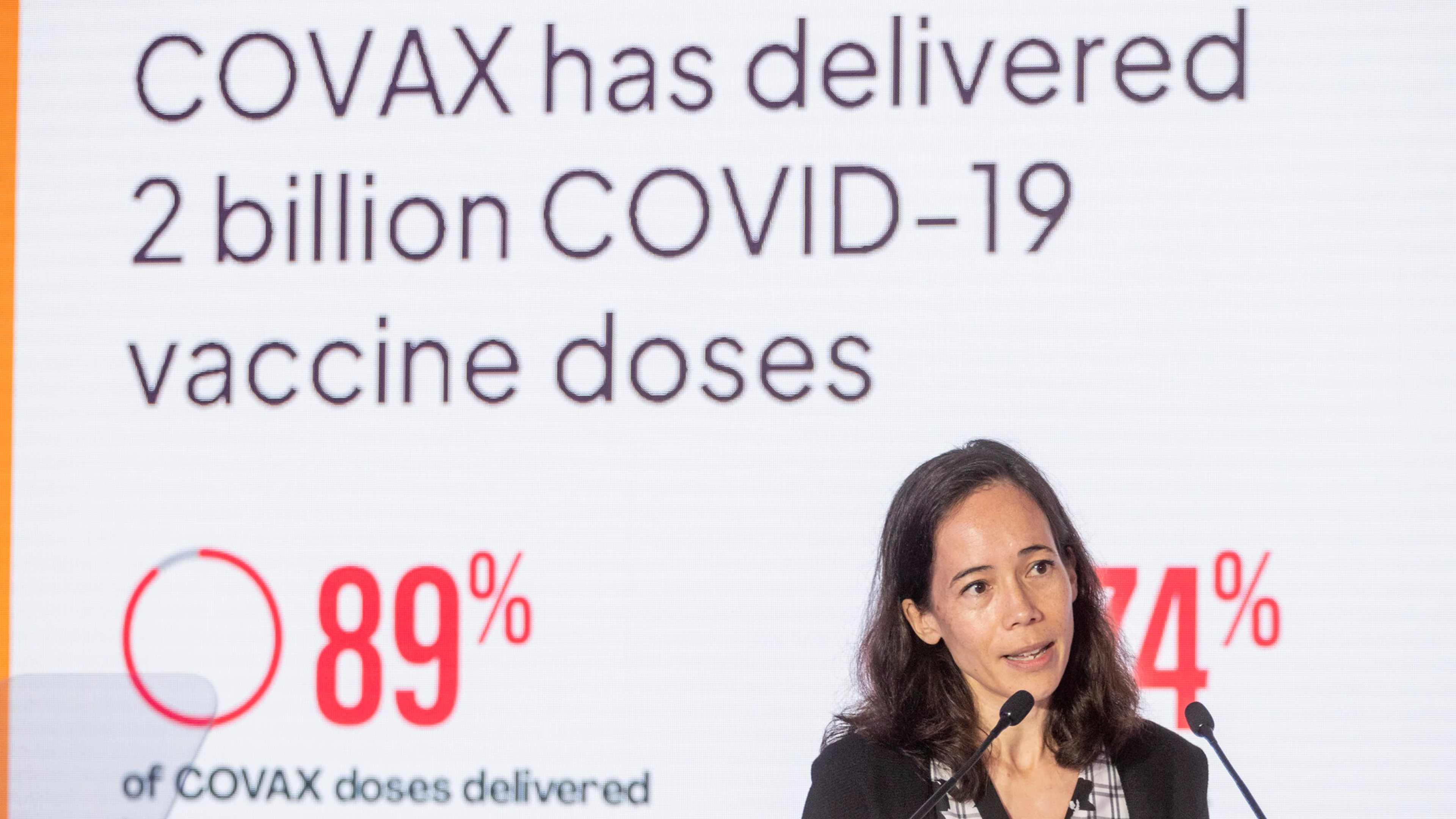

In her reflections, Aurelia describes her own personal eureka moment: the realisation that the driving force of her career is not so much about doing science, but more about enabling greater access to the fruits of science—including protective, life-saving vaccines. She also offers some career tips for women and girls, and discusses how we can begin to inspire them to make scientific progress part of their future.

Can you tell me a bit about yourself and your career so far?

I am French and Vietnamese by origin. I studied Chemistry as my first degree. I’ve also studied management and am a chartered accountant. My career has always been grounded in the life sciences and particularly the issue of access to pharmaceutical innovations in low-resource countries and settings.

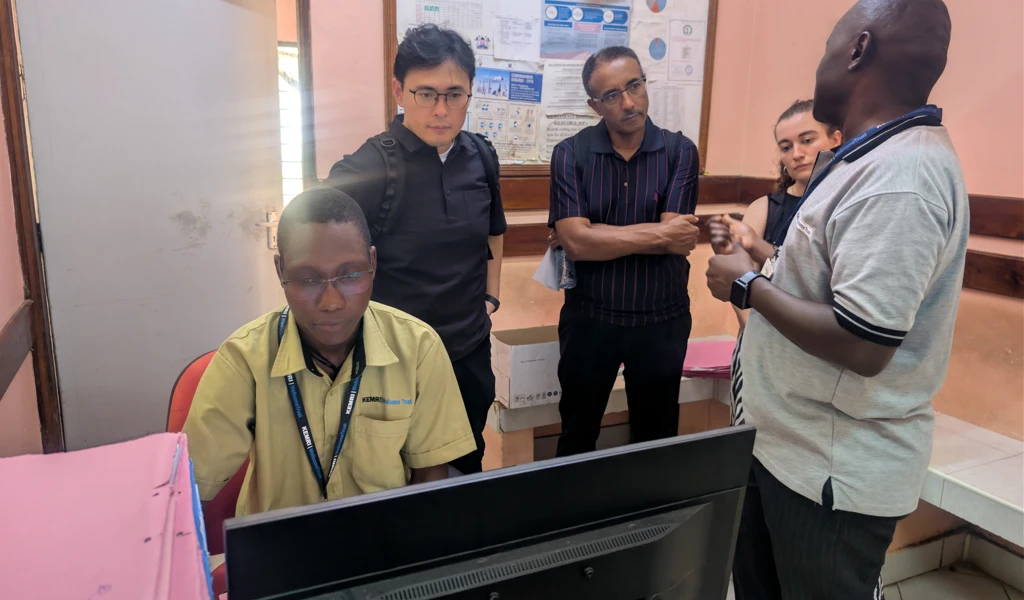

My first roles were across several divisions of GlaxoSmithKline. I specialised in the manufacturing network and worked on acquisitions and disposals of production sites. It was after having done a postgraduate in health policy and financing and a short stint at the World Health Organization working on policies to support generic medicines use that I started working in earnest on access to medicines and vaccines in developing countries. This later led me to work at Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, where I set up the first market-shaping strategy to enable Gavi to buy sustainable and affordable vaccines for the world’s poorest countries, later expanding my work to oversee all of Gavi’s programmes. I also dealt with quite a few disease outbreaks, epidemics and one pandemic, which got me closely involved with CEPI, where I work today as Deputy CEO.

Did you have a role model that influenced your decision to work in science?

It would have to be Marie Curie. I chose to study chemistry as I was fascinated by the periodic table of elements. She was a role model of an outsider who pushed the boundaries of science in a way that the benefits of her research are still applied in daily life today, whether it’s through X-rays or radiotherapy, for example.

What are the greatest challenges you have faced in your career in science? How did you overcome these?

Studying chemistry in the late nineties was still quite a male-dominated affair, and that continued somewhat in the workplace in teams with strong scientific bases. I’ve seen tremendous efforts to increase diversity in recruitment (and not just for gender). But work remains to be done to ensure the small daily biases are reduced, whether it’s giving women an equal share of voice, coaching women to communicate their value and contribution, or mentoring women into roles they may self-select out of. These are all challenges I’ve encountered, and I’ve been fortunate to have role models, managers and mentors – both female and male – to help me overcome them.

Work remains to be done to ensure the small daily biases are reduced.

What has been the best career advice you have received?

The best career advice I’ve been given is: “Do something you enjoy today, and it will lead to something you enjoy tomorrow”.

Too often, students and those in the early part of their careers feel they must ‘put in the time’ into something extremely difficult and unenjoyable. Otherwise, they think they may not get to the next thing. Whatever you choose, it may be difficult, but if there is no joy in what you do on a day-to-day basis, it’s hard to keep going and may not be the thing for you.

Do something you enjoy today, and it will lead to something you enjoy tomorrow.

It took me a while to figure out that it was not ‘doing science’ I enjoyed but making science accessible. That’s how I got to reorient my career and dedicate myself fully to making pharmaceutical innovations available to those who need them the most. It’s this realization that has ultimately led me to my role here at CEPI, where everything we do is guided by access.

It took me a while to figure out that it was not ‘doing science’ I enjoyed but making science accessible.

How can we inspire more girls and women to pursue a career in science?

It starts at an early age. For instance, we still gender-stereotype toys a lot, with those that involve movement (think cars) and mechanical assembly (think Lego technic) being promoted for boys rather than girls. There are many societal nudges that need to be addressed through play, school, higher education, and later the structuring of workplace organization so that women feel they belong and can bring their whole selves to work.

.webp)