How disease survivors’ antibodies shape lifesaving vaccines

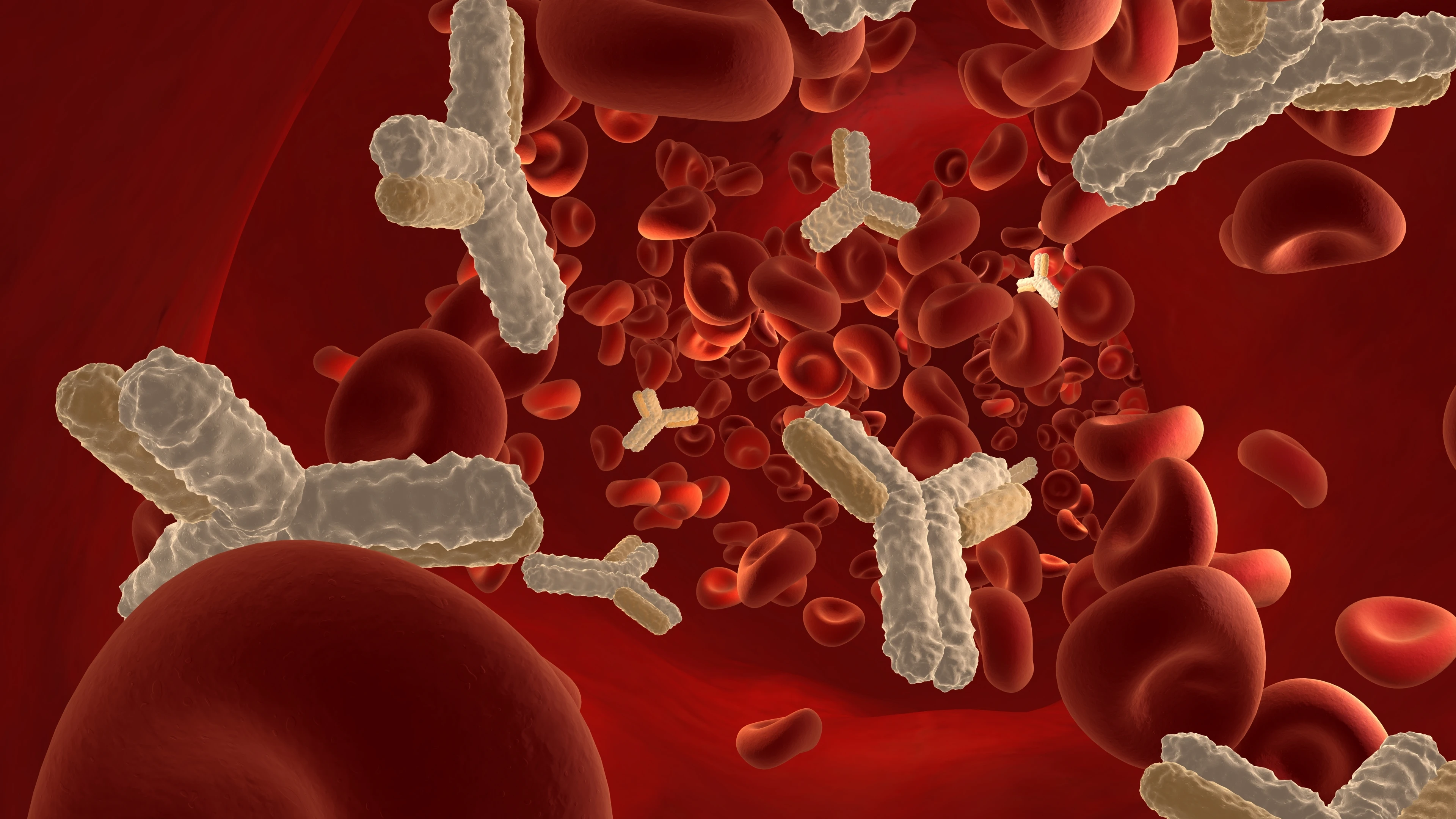

Beyond its most obvious function of sustaining life, human blood can also reveal messages about our health, indicating whether disease might be present or whether we’ve recovered from an illness.

If someone becomes infected by a virus and is able to fight that virus off, it will leave markers in their blood that provide a glimpse into how a person survived and, crucially, how they might be protected from reinfection.

One of these markers are antibodies: the disease-fighting soldiers that alert our body to viral threats and help fight off that virus. But did you know that this information present in the blood of someone who has been infected can also be used to help protect others from future infection of that same virus? By studying the antibodies in a person's blood, scientists can determine the optimum antibody response a vaccine needs to induce to be effective.

Pooling antibody data from serum or plasma from multiple patients who have recovered from a disease and have high levels of antibodies enables vaccinologists to understand what good protection looks like, what level of immunity a vaccine needs to induce for it to offer durable protection, and how a vaccine might perform in humans. This material leads to the creation of antibody standards, which help standardise and harmonise vaccine performance and facilitate regulatory approval.

Creating internationally recognised antibody standards takes the collection of antibody data one step further by helping to ensure vaccine developers around the world are effectively singing from the same hymn sheet. Testing their vaccine samples against the same standards helps to ensure global consistency in evaluating immune responses and promotes a uniform benchmark for vaccine efficacy. The better a vaccine can meet or ideally exceed these standards, the higher the chances of robust protection—an essential step in controlling outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases.

CEPI is a key global funder of critical research into antibody standards for several of its priority pathogens. Take Nipah virus, for example. This lethal pathogen kills up to 70 per cent of the people it infects, and no licensed vaccine is currently available to protect against it. CEPI worked with its partners around the globe to develop the world's first Nipah virus International Antibody standard, published in July 2023.

To achieve this status, the World Health Organization’s Expert Committee on Biological Standardisation (ECBS) must endorse international antibody standards that health and science organisations across the world create. Their endorsement establishes this standard as the globally recognised reference for vaccine developers. And it is this very standard that the Nipah vaccines under development in CEPI’s portfolio are using.

Working with partners like the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), previously known as NIBSC, CEPI has made these standards available at little to no cost, supporting equitable access for vaccine manufacturers, scientists, and regulators worldwide.

Beyond Nipah virus, CEPI has also supported the development of antibody standards against a number of pathogens, including COVID-19, Lassa fever, Rift Valley fever, MERS, SARS-CoV-1, Mpox and Marburg.

And antibody standards aren’t just useful for known diseases—they could also help scientists identify emerging threats, including a potential Disease X. In an emerging outbreak, antibody standards can help scientists rapidly assess whether prior immunity from similar viruses might offer protection.

When SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, emerged in 2019, scientists used antibody tests to check if antibodies from SARS-CoV-1 survivors could recognise and neutralise the virus. This helped researchers quickly determine that SARS-CoV-2 was a new but related coronavirus, guiding vaccine development. Later, the establishment of a CEPI-supported international antibody standard for COVID-19 allowed vaccine developers worldwide to test their candidates against a uniform benchmark, ensuring consistency in evaluating immune responses. Without these standards, it would have been harder to determine which vaccines were truly protective.

.webp)