A little-known virus that is one of the most deadly to infect humans could become the next Ebola, unless the world steps up efforts to halt its spread and develop effective vaccines and treatments.

The story started two decades ago with a few sick pigs in the village of Sungai Nipah in peninsular Malaysia, where local hog farmers were enjoying a boom in pork demand, fuelled by the region's growing prosperity. In September 1998, however, their animals began dying.

Soon the farmers themselves were falling ill, victims of a frightening combination of encephalitis - or brain inflammation - and pneumonia. Doctors were baffled as nearly half of those infected with the mystery pathogen died.

In 1999, a previously unknown virus, now named Nipah, was identified as the culprit.

By then more than 100 people had died, the Malaysian army was deployed to cull over one million pigs, and the virus had jumped across the border into Singapore, where it claimed the life of an abattoir worker.

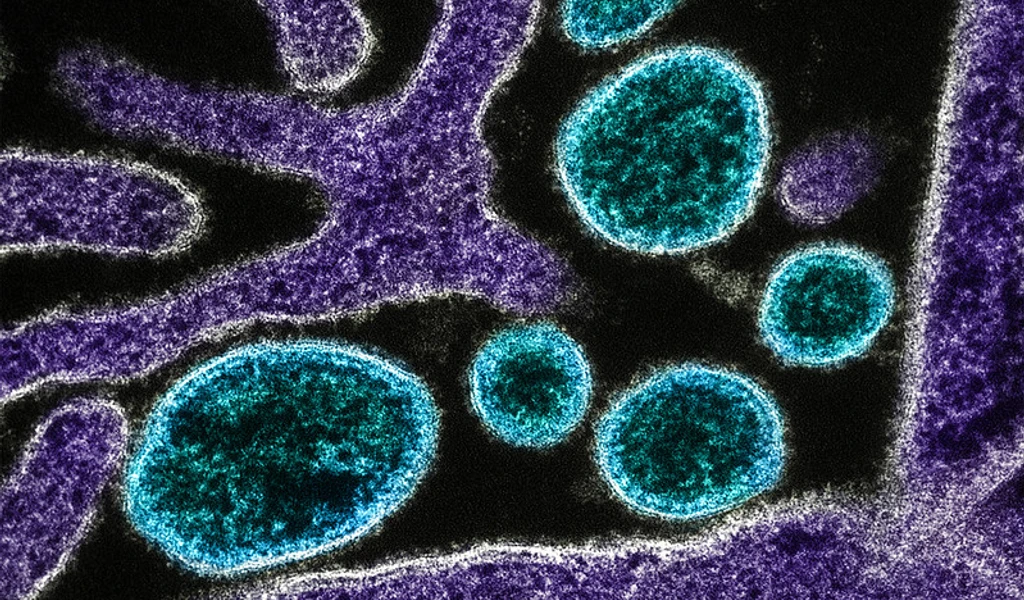

Scientists have since learnt a great deal about this disease and its ecology. It is likely that the infected pigs caught the virus from bats, which form the primary reservoir.

Further important insights into the disease, its ecology, biology and how it causes illness in humans were shared among researchers at the 2019 Nipah Virus International Conference in Singapore in December 2019, the first international scientific conference ever held on the virus.

Despite our increased understanding of the virus that causes it, the fundamental threat posed by Nipah is undiminished.

The virus, which has a mortality rate comparable to Ebola, is on the World Health Organisation's (WHO) shortlist of diseases that pose a public health risk because of their epidemic potential and for which there are no, or insufficient, countermeasures.

Its fearsome reputation helped inspire the 2011 American medical thriller film Contagion, a movie that was praised for its "near-documentary accuracy and precision".

Outbreaks of the Nipah virus continue to occur with worrying regularity and alarmingly high death rates.

While the original Malaysian outbreak was fatal in around 40 per cent of cases, more recent episodes involving fewer victims in Bangladesh and India have killed between 70 per cent and 90 per cent of those infected.

So far, Nipah outbreaks have been confined to South and South-east Asia but the disease has the potential to break out more widely, since the disease reservoir (Pteropus fruit bats, also known as flying foxes) is found across regions of Africa, South Asia and Oceania that are home to more than two billion people.

And since Nipah can also be transmitted from person to person, it could also spread into temperate parts of the world, as the severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (Mers) and Ebola have done.

Following the initial episode in Malaysia, Nipah next emerged in 2001 in Bangladesh and two villages just across the border in the Indian state of West Bengal. Since then, Bangladesh has suffered frequent outbreaks, mostly in winter, with a total of more than 300 confirmed cases over the years.

In Bangladesh, epidemiologists have established that people are particularly at risk if they drink raw date palm sap. Pteropus bats are attracted by the sweet liquid, which they lick as it drips from trees into clay collection pots. This provides an easy route for contamination with bat saliva and urine. The animals can also contaminate fruit such as mangoes.

Last year, demonstrating its wide geographic range, Nipah emerged on the other side of India, in the south-western state of Kerala, more than 3,000km from Malaysia, where the first outbreak was reported 20 years ago.

This time, people are believed to have been exposed after drawing water from a bat-infested well.

The Kerala outbreak killed 17 out of the 19 confirmed cases, with the index case infecting at least 15 other individuals within a few days. Fortunately, it came to the notice of astute clinicians and the cause of the outbreak was identified quickly.

The authorities declared the outbreak contained in June last year, but 12 months later another young man in Kerala was infected (fortunately, he recovered).

There are vast regions where the reservoir species occurs that are not as medically sophisticated as Kerala. What happens if an outbreak occurs there?

Like Ebola, Zika and most other emerging diseases, Nipah is a zoonotic virus, meaning it passes from animals to humans. The immediate advice for people in Nipah-prone areas is to avoid contact with bats and sick pigs.

But zoonotic threats raise bigger issues about human interactions with wildlife since climate change, habitat destruction and human encroachment into previously isolated areas have created a fertile space for viruses to hop between species.

A vaccine would be a potent tool against Nipah as vaccines are the one technology that can stop an infectious disease dead in its tracks. But the fact that Nipah is a relatively rare tropical disease severely limits the incentive for drug companies to invest in vaccine development.

Fortunately, my own organisation, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (Cepi), was set up in 2017 to assist in just these circumstances and we currently have four early-stage Nipah vaccine candidates in our portfolio.

The WHO priority list mentioned earlier also includes Ebola, Zika, Lassa fever, Mers and all the as-yet unknown pathogens, which are collectively represented as "Disease X."

It is sobering to remember that Nipah was once Disease X and that many more such diseases are out there, waiting to emerge, waiting to find their way into unprepared human populations.